{

"authors": [

"Marzia Cimmino"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [

"Eurasia in Transition"

],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

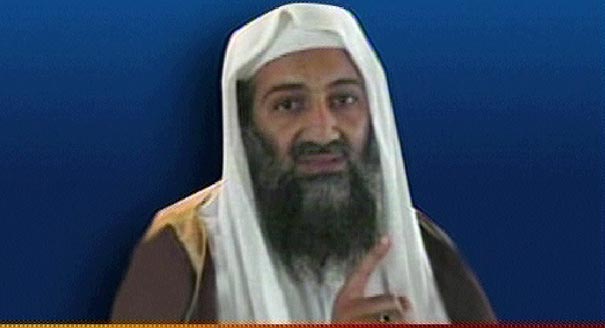

After Osama bin Laden: A View From Moscow

Russian experience in fighting terrorism shows that the elimination of charismatic leaders like Osama bin Laden does not necessarily end the deadly threat posed by the terrorist groups they led.

Source: Aspenia online

The threat of terrorism has been a top priority in the list of Moscow’s national security challenges. The most severe threat comes from the republics of the North Caucasus. Russia’s southern fringe persistently bubbles in a deadly stew of separatist claims which have transmuted into jihadism. Islam is increasingly becoming the main pillar of belief in Caucasian societies after the fallout of communism and after aborted attempts of modernization. In 2007, a self-proclaimed Islamic separatist state-territorial group in the North Caucasus called “Caucasus Emirate” was founded. The main leader, Doku Umarov, has claimed responsibility for numerous terrorist acts, including the bombings at the Moscow metro in 2010 and at Domodedovo International Airport in January. In June 2010, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton officially added Umarov to the US State Department’s ‘black list’. It is no secret that al Qaeda regularly supported terrorist organizations in Russia like the Caucasus Emirate.

Russia has experienced a massive emotional shock from terrorist attacks, including the hostage crisis at the Dubrovka Theatre in 2002, the tragedy at the Beslan School in 2004, the collapse of two apartment blocs in Moscow in 1999, and the recent bombings in Moscow. The response by authorities has been forceful and straightforward: direct and unrestrained application of military force against the source of this violence - which was identified as armed underground resistance groups in the North Caucasus. Large groups of terrorists led by Shamil Basayev, Salman Raduyev, Ibn Al-Khattab and Said Buryatsky – all of whom have been killed - were decimated. However, the physical elimination of these terrorists and combatants did not radically change the situation at all.

Russian (mis)management of terrorist threats provides three crucial observations in relation to bin Laden’s death. Firstly, the strategy of killing charismatic leaders, like bin Laden, and brutally destroying terrorist groups, oftent results in unexpected and negative consequences. Local resentment and alienation promote the adherence to alternative ideologies, like jihadism. For instance, when two female suicide bombers killed 40 people in the Moscow metro bombing, the Russian security services immediately defined them as a pair of “black widows”. Such women are called black widows because they have usually lost their husbands, brothers or close relatives in clashes with Russian-backed forces. They are usually poorly educated, grieving and thirsty for revenge. Consequently, they join terrorist groups that offer concrete prospects of retaliation. As Alexey Malashenko at the Carnegie Moscow Center stated, “Extremism has a habit of breeding charismatic figures. Bolshevism certainly did not disappear after Vladimir Lenin’s death. Thus, the jihad will continue”.

Secondly, the Caucasus Emirate epitomizes the local nature of terrorist organizations. The network structure of modern terrorism does not imply any central control. Al Qaeda acts through the synergetic efforts of autonomous regional cells. The Caucasus Emirate and the other regional cells in Mesopotamia, the Maghreb and in the Arabian Peninsula receive regular financing and support from bin Laden’s brainchild, al Qaeda. Nonetheless, their political goals usually consist in changing local conditions and obtaining more influence in the region. A successful strategy to defeat international terrorism entails undermining the power of its local cells. In this regard, Kazakh Foreign Minister Yerzhan Kazykhanov declared at a meeting of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization that the situation in Afghanistan will keep the tension high in the region, remaining a source of terror, extremism and illegal trafficking of drugs and weapons. In other words, the presence of ethnic conflicts, organized crime, weak central governments and religion compound the efforts to eradicate terrorism. Law enforcement, narco-business, terrorism and war are essentially four branches of the same encompassing and self-sustained enterprise. And a perverted but workable incentive structure has emerged over the past decade that sustains terrorist groups, with or without bin Laden.

Thirdly, political leaders need to directly engage populations under the influence of local terrorist organizations. Civilians represent the most fragile element in the fight against terror because their suffering and alienation make them easy prey for terrorists. The black widows, for instance, symbolize how, after years of war and desires for revenge, civilians are easily recruited by Islamic extremists. This occurs when the central government or the authorities that fight against terror underestimate the urgent need to protect civilians from the manipulation and indoctrination of terrorists. “Black widows” and suicide bombers are themselves victims of the perverse means adopted by terrorist leaders to fulfill their own goals. For these reasons, Russian President Dmitry Medvedev made a dreadful mistake when he refused, at the last minute, to meet with the mothers of the victims of the Beslan School in May of 2011 - fearing political damage in the context of the upcoming elections in 2012.

Russia’s longtime struggle against terrorism has led to mixed results. Accordingly, Russian experts and policy makers have tempered the triumphant tones of many European countries and the US after the news of bin Laden’s death. Their skepticism originated from key lessons learnt during the bloody and enduring war on terror on Russian soil. Ultimately, charismatic leaders were replaced and, in the worst case scenarios, their deaths brutally avenged. Al Qaeda is also made up of regional cells, with local demands and conditions that independently feed terrorism. A bottom-up approach is therefore needed in order to eradicate these cells and their international impact. Lastly, the protection of civilians is key in the future success of counter-terrorist policies. The liquidation of bin Laden will provide President Obama with an unbeatable weapon in his re-election campaign, yet it will not eradicate the deadly threat of al Qaeda and its cells around the world.

Marzia Cimmino is an intern at the Carnegie Moscow Center.

About the Author

Marzia Cimmino

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.