Alexander Baunov

{

"authors": [

"Alexander Baunov"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

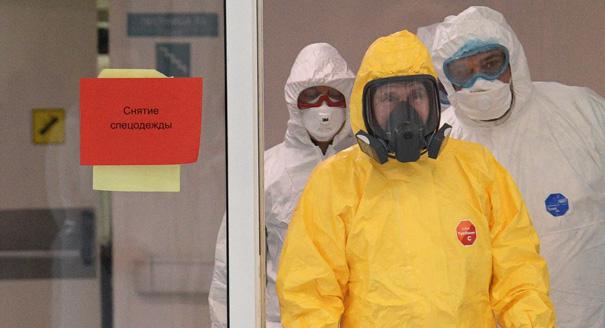

Source: Getty

Why Turkey’s Military Coup Is Impossible in Russia

The military takes over when it feels superior to the rest of society. Its perceived superiority lies in the view of the army in developing nations as the primary instrument of modernization. The Turkish coup failed because soldiers have lost that status in Turkish society—a process that happened long ago in Russia.

The attempted coup in Turkey on July 15 has prompted both comparisons to the Decembrists, the group of liberal Russian revolutionaries who failed to take the St. Petersburg government in 1825, and predictions that new Decembrists with helicopters could take to the streets of Moscow. This is outside the realm of possibility.

Military coups don’t just occur out of the blue. The military takes over when it feels superior to the rest of society and refrains from doing so when it feels equal to—or beneath—the people.

When the military considers itself superior to society, the soldiers believe they’re ahead of the nation. They look down on politicians, merchants, bureaucrats, the intelligentsia, and the common people. In countries where the military is a de facto branch of the government, the soldiers get perks beyond their salaries, which places them above their civilian colleagues. In these nations, military personnel are based in small upscale towns, where they live in new houses in clean, safe communities in an otherwise chaotic, poor society. They vacation in elite resorts, have access to proper medicine, and receive a pension and a good education.

In these societies, most people agree that the soldiers are the elite. The military’s high self-value goes hand in hand with its high societal value. Its academies provide the best education in the country. Rich and influential families send their children to military schools and later into the service: they’re proud when their offspring don a uniform. Army salaries are higher than civilian salaries and military status grants access to social benefits and, for high-ranking officers, a commanding role in the economy. The military represents and perpetuates the old elite, but also provides the most flexible social ladder, one that allows upward mobility for the hardworking newcomer.

This is the situation in Turkey, Egypt, the Arab world, Pakistan, Thailand, some countries in Africa—and formerly in Spain and Latin America. There, sociopolitical “corrections” have regularly occurred with the help of military coups.

But none of this describes Russia, Europe, North America, China, and South Africa. Forget about the Western countries, nations where military coups are in all likelihood impossible due to developed political institutions. In the remaining countries, the military plays strikingly different roles.

The relative privilege of third-world militaries stands in stark contrast to the pitiable state of the Russian soldier: the low (in fact, quite standard) wages, the small pension, the dependence on a spouse for supplementary income (it would never occur to an Arab officer to ask his wife to work).

Even if Russia’s biggest institutional failures were patched up, the military profession would still be equal to others, the way it is in the West: just a job. Political and business elites will never dream of sending their children to a Suvorov Military School and then on to a position in the army, which in both the United States and Russia is viewed mostly as a good career option for lower-class families.

Soldiers in Russia are respected professionals, but are by no means viewed as moral custodians, tasked with preventing societal corrosion from ignorant hoi polloi. On the contrary, they’re part of the masses and their ideology is the same mix of conservatism and patriotism that you would find in any civil profession.

The key to the perceived superiority of the military in some countries lies in their belief about modernization. Militaries supplant the rulers—and the intellectuals don’t bat an eye—because they see themselves as modernizers; the scientific vanguard; a social class that’s a few steps ahead of the masses, thinks more radically, lives more freely, and understands the direction in which they’re moving.

It’s obvious where the militaries of developing nations get this agenda. In nations suffering from arrested development, the first move of the ruler seeking to lead the country forward—such as Russia’s Peter the Great—is often to modernize the army.

In countries that are still catching up, when there are no serious and permanent institutions, the military fills the vacuum. Political parties, the press, the courts: everything is somewhat make-believe, but the army is for real. The Turkish coup—the country’s fifth in half a century, and the first not to succeed—didn’t fail because of lackluster preparation. The military failed because soldiers have lost their status in Turkish society.

It’s not enough that the military see themselves as modernizers: their opinion must be shared by society overall. And society no longer saw the soldiers in this role.

Modernizers arise organically in areas where the country is lagging, and in neither Russia nor Turkey is the military fit to play the role of modernizing agents of change.

Russia is not lagging behind in terms of its military professionalism. We have had Western-style regiments for three hundred years. The economy is another matter. The rulers of Russia—and also the rulers of Iran, Belarus, and a number of other countries, not to mention Erdoğan’s Turkey—must tolerate and support a progressive business and economic class, which keeps their country integrated in the global economy.

It’s clear why there are no military coups in countries with developed democratic institutions—the West and Japan—but it’s equally clear why there are no coups in India, China, and contemporary Latin America. The soldiers have had their time as instruments of change, and as modernity spread to other groups they lost their status as the modernizing social class. And they understand that.

The failed coup in Turkey illustrated this perfectly. In dynamic modern Turkey, a key part of the global economy, it was absurd to think that a tank regiment deployed to the bridge over the Bosporus could symbolize progress. The uniforms of the coup plotters seemed far more archaic than the headscarves of the women supporting President Erdoğan.

Russia passed this phase much earlier in its history. Society has long been too complex for the men in uniform to be the sole instrument of modernization. If during the reign of Peter the Great they were seen as such, by the time of Alexander II’s rule (1855–1881) that was simply not the case. The military in Russia is not society’s seat of progress and modernization.

Furthermore, countries that have experienced revolution—like Russia—are inclined to weaken the force of the military. In post-revolutionary societies, different groups play the role of modernizers: revolutionary parties, for example. Just as the role of the army was diminished in communist China and Islamic Iran, the Russian army has not only passed its stage of superiority, but has also been purposefully lowered in its rank.

This is why in Russia military coups are a thing of the past. The last one, you could say, occurred on December 14, 1825, and it’s unlikely we’ll see another any time soon.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Baunov is a senior fellow and editor-in-chief at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

- Could Russia Agree to the Latest Ukraine Peace Plan?Commentary

Alexander Baunov

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya