Andrey Pertsev

{

"authors": [

"Andrey Pertsev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

YouTube Spawns New Generation of Russian Political Stars

The Russian electorate has regressed in its demands and gullibility to where it was in the early 1990s, when firebrand politician Vladimir Zhirinovsky had his first success. Russian society has a soft spot for wisecracking politicians who give populist speeches and bash the government, even if they tend to contradict themselves.

Russian politics has some unlikely new heroes in the form of stars of YouTube and social networks. Several candidates running in September’s elections for Russia’s lower house of parliament, the State Duma, launched their political careers by speaking at public events or posting speeches on YouTube, after which their criticism of the government attracted tens of thousands of shares.

The public, disappointed with the government, doesn’t want to hear the truth. It wants to hear established problems discussed using familiar language, and if this criticism mimics the witty sound bites of stand-up comedians, better still. Opposition voters are looking for someone like Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the infamous rabble-rousing founder of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR). Their mindset has returned to that of the early 1990s when, after years of Soviet stagnation, voters developed a yearning for outspoken demagogues.

Now they have a chance to elect these new voices of the people in the upcoming Duma elections. Businessman Dmitry Potapenko, who embarked on a public tirade about problems faced by Russian business at last year’s Moscow Economic Forum, will run for the Party of Growth. Kursk Oblast local legislator Olga Li, who made a YouTube appeal to President Vladimir Putin against state corruption and “the propaganda of violence on TV,” will represent the Yabloko party. Vasily Melnichenko, a quick-witted farmer from the Urals who speaks in sound bites—“The problem isn’t that our country is up the creek without a paddle, the problem is that it’s starting to get comfortable there”—ended up on the ballot of the Greens.

These new political heroes are, however, the product of their words, not their deeds: little is known about their real-life efforts. And in fact, their background and personal convictions don’t even really matter. Melnichenko’s views are fairly pro-government, but for a long time he has been a member of former finance minister Alexei Kudrin’s Civil Initiatives Committee and has participated in the same events as Yabloko representatives. Li ran for the Kursk Oblast legislature on the ballot of the Communist Party and her newspaper, Narodny Zhurnalist, has been accused—not without grounds—of cooperating with the government, as well as of publishing paid-for materials; however, anti-corruption crusader and opposition activist Alexei Navalny shared her video, and now Li is on the Yabloko ballot.

Russian society has a soft spot for wisecracking politicians who give populist speeches and bash the government without bothering with deep analysis. For many years, Zhirinovsky filled that niche, but the LDPR leader is getting old and Russia needs a new generation of politicians. Limits on freedom of speech have contributed to the search for new heroes of speech: the pond has gotten smaller in recent years. This is why Melnichenko’s and Potapenko’s videos are often shared under headlines such as: “You’ll never see this on TV. This guy tells the whole truth.”

The audience values the very existence of the quotes: direct, catchy, and eloquent, though vague, without details or statistics. As with Zhirinovsky, the tonality of the speeches can range widely. One day the Kremlin is the problem; the next day it is the solution, while the West or nameless bureaucrats are the problem. Opposition activists snatch up the former quotes, while patriots and pro-Kremlin activists opt for the latter.

The trick is that the new heroes openly say what the populace is thinking, using familiar language: “thieving officials, billion-dollar embezzlement, bulldozered geese.” There are no deep discussions, nothing complicated, no big words. This could be your next-door neighbor talking about the latest news—except unlike these new heroes, your next-door neighbor doesn’t have the guts to say such things publicly.

There is some similar commentary on TV, though not the kind of direct criticism of Putin and his inner circle heard from Li. A number of opposition politicians such as Boris Nadezhdin, Leonid Gozman, Vladimir Ryzhkov, and Irina Khakamada make the rounds on national TV talk shows; occasionally someone from the non-systemic opposition, like the Democratic Choice party, appears. However, their speeches never resonate so widely, even though the potential audience on national TV channels is much bigger than on YouTube.

The source of information plays a major role in the psychology of perception: even though the Internet is everywhere now, it still has a certain forbidden aura, like the samizdat (clandestinely distributed texts) and the jammed radio broadcasts of the Soviet era.

TV viewers suspect talk show guests of hypocrisy. Potapenko or Melnichenko might go on TV, but playing a certain role. If they deviated from the script, this would be remedied in the editing room. Furthermore, any statement made on a talk show can be neutralized by an opponent—or better yet, multiple opponents. The YouTube videos, on the other hand, are monologues that no one interrupts or jams. The YouTube stars look like novices who tell the truth and are not just playing a role, and their words are perceived as genuine.

Li, Melnichenko, and Potapenko owe their popularity in part to the government, which obstructs authentic discussion on TV. This is what happened under the Soviet regime to 1980s underground rock groups like Kino, Alisa, Aquarium, DDT, and Televizor, whose recordings were distributed on cassettes. Russians dissatisfied with the situation in the country listened to the songs, but the bands couldn’t perform at major venues. The underground rock groups weren’t as polished and saccharine as the bands approved by the government, but they played from the heart.

The Kremlin is not afraid of the new political heroes, whose generic statements don’t go beyond words and aren’t heard by the widest audience. In fact, Internet politicians can even play into the hand of the government: Potapenko’s and Li’s names on the ballots will serve as additional evidence that even Putin’s most ardent opponents are allowed to take part in the elections. But the popularity of the YouTube whistleblowers reflects a dangerous trend: the Russian electorate has regressed in its demands and gullibility to where it was in the early 1990s, when Zhirinovsky had his first political success. Now the voters have to progress anew: learn to read biographies, compare quotes from different eras, search for ideological subtexts, and demand real plans.

About the Author

Andrey Pertsev

Andrey Pertsev is a journalist with Meduza website.

- The Kremlin Is Destroying Its Own System of Coerced VotingCommentary

- Why Is the Kremlin Punishing Pro-War Russian Bloggers?Commentary

Andrey Pertsev

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

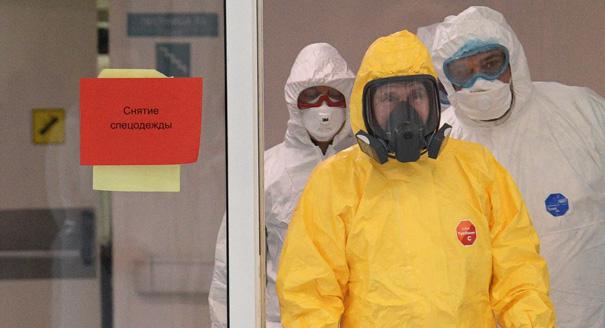

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya