Alexander Baunov

{

"authors": [

"Alexander Baunov"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

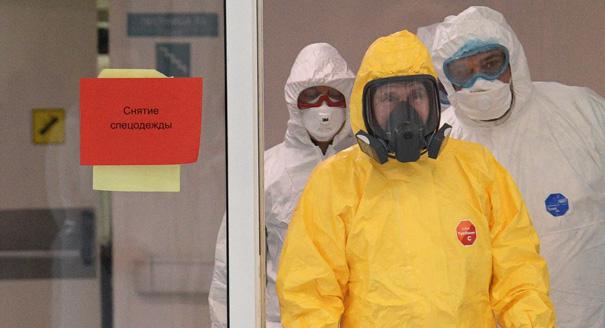

Source: Getty

The Storm Clouds of 2017: Russia’s New Protests

The recent mass anti-corruption protests called across Russia on March 26 pose an unexpected challenge to the Kremlin. The protesters are younger and less prosperous than their counterparts in 2011–2012. If Russia is on the brink of a new kind of revolution, then all sides need to act responsibly.

If the Russian authorities thought they could mark the anniversary of the 1917 October Revolution in a dull and peaceful way, they may need to think again.

After the nationwide anti-corruption protests that rippled across Russian towns and cities on March 26, the current regime in the Kremlin now has some revolutionary material to work with. This at least gives the authorities the chance to show that they can deal with street protests better than previous Russian rulers did.

It has long been accepted wisdom that Russians, in contrast to people of other nations, are indifferent to the material wealth of their leaders, maybe because they are accustomed to this situation or because they wish they could be so lucky. Or perhaps, the story goes, Russians remember that the last effort to strip the elite of its privileges, in the perestroika period, ended up with ordinary people losing even more.

Of course, neighboring Ukraine also had its anti-corruption revolt in 2013, the Maidan, but that was made easier by the perception in Kiev and elsewhere that Viktor Yanukovych was an outsider, not “one of us.” That is not the case in Russia, and history suggests that Russians are generally prepared to put up with this kind of arbitrary rule for even longer.

This makes the fact of mass unauthorized demonstrations to protest against the alleged corruption of prime minister Dmitry Medvedev—as revealed by anti-corruption campaigner Alexei Navalny—even more surprising.

Medvedev still looks young and willing to engage with the modern world through gadgets and use of social media. He seems to be much closer to the young protesters than grim-faced directors of state-run enterprises like Igor Sechin. Yet the scale of last Sunday’s rallies shows that Medvedev had also managed to alienate a lot of people across Russia.

Perhaps many of the protesters were former supporters of Medvedev, irked by the realization that he is not as close to them as he seems and still resentful of the way his once-promising presidency ended with him handing back the keys of the Kremlin to Vladimir Putin in 2011. That action was the cause of the last round of mass protests to shake Russia in the winter of 2011–2012.

There are two important differences between last weekend’s protests and those of 2011–2012. The current ones are unusual for being triggered not by a specific event, such as an election, murder, or arrest, but by what is generally considered a permanent and unchanging phenomenon in Russia: high-level corruption. They were also much wider in scope geographically, embracing the whole of Russia. In fact, they were probably the biggest of their kind since the perestroika period and the end of the Soviet Union in 1991.

These protests were not concentrated just in Moscow; they were less “glamorous”—as their detractors liked to call them at the time—than the ones of five years ago. In 2011–2012 it was the Moscow middle class that mainly voiced its discontent, demanding that the state treat it with respect. In that sense, it was a protest about prosperity as well as dignity. The current protest is both more naïve and more terrifying for the authorities. It is an uprising of the poor, not confined to Moscow but with a wide regional span across more than 100 cities. That undermines the Kremlin’s story that this is merely about spoiled Moscow brats rocking the boat while the regions crave stability.

Although we lack exact data, the demonstrators also seem to be younger now. Many of them appear to have been first-time protesters. In the absence of an obvious political crisis, any protest movement needs a large number of very young and fearless participants who are guided only by general feelings of discontent with the economic situation and a sense of injustice about the world. And when the authorities crack down hard on teenage protesters, that tends to draw in grown-ups too.

Having promised to demonstrate that they can handle revolution better than the unfortunate last tsar of Russia, Nikolai II, the current rulers in the Kremlin have to walk a fine line between a forceful response and excessive violence. They should know that the people being unhappy with someone’s palaces isn’t a good enough cause for a revolution, but a response with excessive violence is. That is what happened as a result of Viktor Yanukovych’s crackdown on the Maidan in 2013. While seeking to discourage protests, the Russian regime will have to respond in a way that won’t actually encourage them.

Identifying Medvedev, an ostensibly liberal government official, as the target of protests has also strengthened the protest movement. Many decry Navalny for being ambiguous and cowardly in his decision to go after Medvedev rather than, say, President Putin or Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov. But once the defenders of liberal Medvedev authorize a full-scale crackdown on dissent, divisions within the protest movement will disappear. A harsh response eliminates the distinction between officials who are good or bad, close or distant. In that context, everyone becomes distant and bad.

As for Medvedev himself, the protests are expected to weaken his clout inside the system, but for the time being they will also make him stronger on the outside. As long as the system works the way it always has, no government official can be removed as a result of street protests. If the regime’s adversaries—the opposition, the State Department, street protesters—picked Medvedev as the system’s weakest link, then that link must be strengthened. So in the short term at least, the protests will have the opposite effect of what is intended.

It was perhaps inevitable that the intra-elite struggle that has broken out in the transition period that precedes Putin’s reelection in 2018 for his final term in office would also be waged on the streets. But this is not the kind of managed public politics members of the ruling elite intended. Yet the dangers to the entire regime are so high here that it is impossible to call Alexei Navalny, who has now asserted himself as Russia’s main opposition figure for the third time (after the 2011 protests and the Moscow mayoral election), a pawn in someone else’s political game.

That fact makes the situation more clear, but not less complicated. We traditionally demand that the government act responsibly, but the tragic experience of the revolution Russia endured a hundred years ago (an experience whose meaning, arguably, we have still not fully grasped) means we must also demand responsible behavior from the opponents of the government, especially the revolutionary-minded ones.

The storm clouds that broke over 1917 are still present in Russia’s historical memory. The Project1917 website of Mikhail Zygar features testimonials from the participants of the 1917 events that resemble social network posts of today. We read how people celebrate, cheer, and express doubt and indignation. When reading the posts written by poets, high school and university students, journalists, noble officers, and selfless housewives, we can’t help but be on their side. But we also know what happened next. If we reject that historical knowledge, even out of the best intentions, we will be betraying many fine and honorable people from both our past and present.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Editor-in-Chief, Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center

Baunov is a senior fellow and editor-in-chief at the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center.

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

- Could Russia Agree to the Latest Ukraine Peace Plan?Commentary

Alexander Baunov

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya