This blog is part of ENGAGE, a project that examines challenges to global governance and EU external action. A consortium of thirteen academic institutions and think tanks seeks to assess the EU’s ability to harness all its foreign policy tools and identify ways to strengthen the EU as a global actor.

***

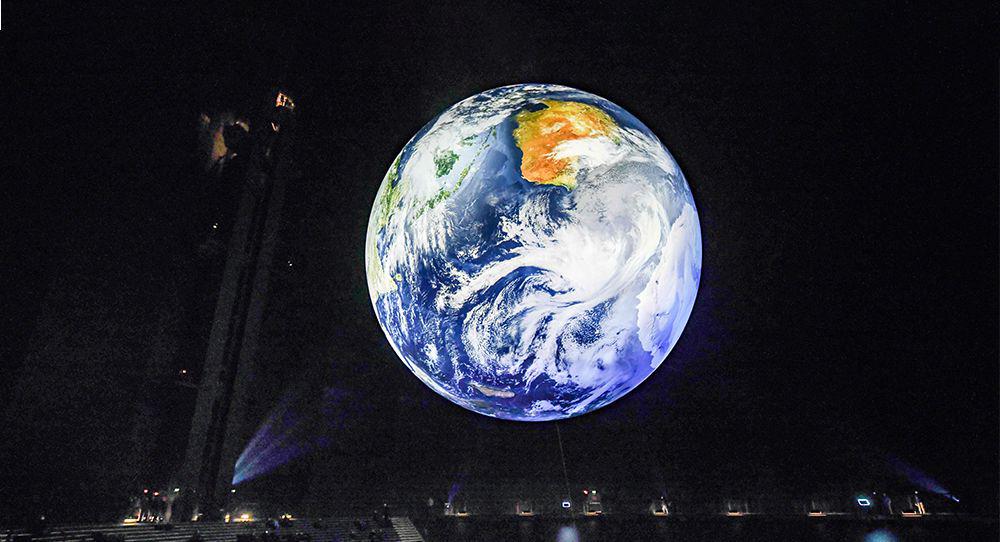

After a year of disasters and crises, it is time for negotiators from 197 countries and the EU to gather once again to discuss the systemic calamity in our present and possible future.

Starting next week, world leaders and thousands of national representatives will meet in the Egyptian resort of Sharm el-Sheikh for COP27, the annual UN climate negotiations forum.

Some civil society members, including Greta Thunberg have announced they will skip the COP, to condemn the sluggish pace of progress of the negotiations while protesting the human rights record of this year’s COP presidency.

And there is no doubt that climate action is progressing far too slowly.

The climate disasters of 2022—droughts in China and Europe, flooding upending 33 million Pakistani lives, and floods, droughts, and wildfires in numerous African countries, to name a few—are telling signs, occurring at “just” 1.1 degrees Celsius of warming. As the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) put it this month, the window to stabilize the climate is rapidly closing.

COP27 is a critical opportunity to stop that window from slamming shut. But the leadup to this conference has been tremendously challenging. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has created enormous security, economic, energy, and food-related fallouts, leaving governments and citizens scrambling for solutions. Amid this chaos, a major question loomed: would the fight against climate change and progress on the energy transition become further victims of Russia’s war?

According to the newest data by the International Energy Agency, the answer is no.

Rather, the reverse has occurred: the energy crisis and high fossil fuel prices brought about by the weaponization of energy have helped governments take further measures to limit their dependence on these fuels, potentially hastening the energy transition. For the first time, demand for fossil fuels is expected to peak or plateau across all the IEA’s scenarios.

For the EU, in the short term, this trend is arguably not as visible: member states that had pledged coal shutdowns have fired up plants once again to ensure electricity supply. In the mid to long term, however, the shock of Russia’s brutal war on Ukraine has led the EU to strengthen its decarbonization trajectory.

The combination of the REPowerEU Plan, launched in the face of Russian aggression, and the ongoing push for Fit-for-55 legislation is bringing the EU ever closer to the trajectory to reach a 55 percent—or even higher—reduction in emissions by 2030.

The deal is not yet sealed: many policies remain on negotiators’ tables, and the EU must remain vigilant to avoid locking in a carbon-intensive future amid its rapid moves to ensure security of supply in the short term. On the whole, however, the EU is leading the way on transforming climate ambition into reality.

Despite all the bad news this year, some light seems to be emerging. Climate change has not dropped off policymakers’ agendas, as it arguably did following the 2008 crisis. And the Paris mechanism appears to be working: before 2015, our collective path was leading to 3.5 degrees of warming by 2100—seven years later, this number has come down considerably.

But much more is needed, both in ambition and implementation. When it comes to ambition, if all national climate plans (nationally determined contributions or NDCs, in climate jargon) are implemented, we are heading for a 2.4 or 2.6 degree future, overshooting the Paris Agreement temperature goals of 1.5 or 2 degrees by a long shot.

Even that dangerously hot future, however, relies on the premise that governments will implement the policies needed to achieve the NDC targets. And at present, this is not yet the case: if current policies are executed without any change, the world would be 2.8 degrees warmer by 2100.

Setting targets, particularly long-term targets for 2050, 2060, or 2070, is easier than designing and executing the policies and measures to put economies on the course to attain those objectives. COP27, therefore, will focus not only on shiny new emissions reductions targets by 2030 or 2050: in Egypt, it is also time to get real about implementation.

But while negotiators focus on mitigating climate change to avoid its worst effects, the heating we have accumulated has already baked in some of those effects. Countries and populations will have no choice but to adapt to their changing climates—and vulnerable states with little historical responsibility for climate change are feeling the brunt of its impacts, while having the lowest capacity to adapt. Although adaptation is one of the key pillars of the Paris Agreement, attention to this component has always been lacking. At this COP, held in Africa, it is sure to rise to the top of agendas.

The need to urgently step up action in both mitigation and adaptation will undoubtedly connect with a major elephant in the room: climate finance and its cousins.

Developed countries have failed to meet their promise of supplying developing countries with $100 billion in annual climate finance by 2020—but even this number is far below actual financing needs. Moreover, the multilateral development bank system needs updating to provide the finance for today’s climate realities.

Beyond actionable finance, there is the question of loss and damage: the material and immaterial losses from climate change, which cannot be recovered, and for which some vulnerable states are seeking compensation. This issue, which has been on a slow simmer in UNFCCC negotiations for a long time now, is one of the most likely to come to a boil during COP27. The EU and US have signaled willingness to discuss this topic, but skillful diplomacy will be needed to address the issue.

Although climate change has not fallen off the agenda amid the polycrisis of 2022, the agenda for COP27 is heavily loaded, and many thorny discussions await. Negotiators at Sharm el-Sheikh face a daunting, vital mission. Fudging is not an option.

Marie Vandendriessche is a senior researcher and research coordinator at the EsadeGeo Center for Global Economy and Geopolitics (Barcelona/Madrid).

.jpg)