Source: Foreign Policy

Think Again: Arab Democracy"The Berlin Wall Has Fallen in the Arab World."

Think Again: Arab Democracy"The Berlin Wall Has Fallen in the Arab World."

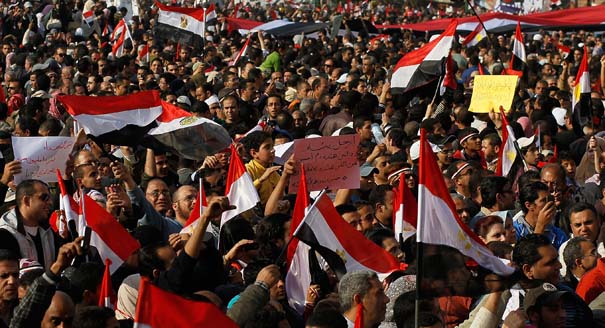

Yes and no. It's tempting to compare the astonishing wave of political upheaval in the Arab world to the equally dramatic wave of political change that swept Central and Eastern Europe in 1989. In the Middle East today, as in 1989, extraordinary numbers of ordinary people are courageously and for the most part nonviolently demanding a better future for themselves and their children. The wave broke just as suddenly and was almost entirely unpredicted by experts both inside and outside the region. And the process of cross-country contagion -- the political sparks jumping across borders almost instantaneously -- has also been strikingly reminiscent of Central and Eastern Europe in that fateful year.

Yet the 1989 analogy is misleading in at least two major ways. First, the communist governments of Central and Eastern Europe had been imposed from the outside and maintained in place by the Soviet Union's guarantee -- the very real threat of tanks arriving to put down any serious insurrection. When Soviet power began to crumble in the late 1980s, this guarantee turned paper thin and the regimes were suddenly deeply vulnerable to any hard push from inside.

The situation in the Arab world is very different. For all you hear about America's support for dictators, the Arab autocracies were, or are not, held in place by any external power framework. Rather, they survived these many decades largely by their own means -- in some cases thanks to a certain amount of monarchical legitimacy well watered with oil and in all cases by the heavy hand of deeply entrenched national military and police forces. True, the United States has supplied military and economic assistance in generous quantities to some of the governments and did save Kuwait's ruling Sabah family from Iraqi takeover in 1991. Generally, however, the U.S. role is far less invasive than that of the Soviets in Central and Eastern Europe -- just ask American diplomats if they feel like Saudi Arabia's independent-minded King Abdullah is a U.S. puppet.

What's more, though citizens in some Arab countries have given their governments a hard push, the underlying regimes themselves -- the interlocking systems of political patronage, security forces, and raw physical coercion that political scientists call the "deep state" -- are not giving up the ghost but are hunkering down and trying to hold on. Shedding presidents, as in Tunisia and Egypt, is a startling and significant development, but only partial regime collapse. The entrenched security establishments in those countries are bargaining with the forces of popular discontent, trying to hold on to at least some parts of their privileged role. If the protesters are able to stay mobilized and focus their demands, they may be able to force a step-by-step dismantling of the old order. Elsewhere in the region however, the changes so far are less fundamental.

Second, Middle East regimes are much more diverse than was the case in Central and Eastern Europe. The Arab world contains reformist monarchs, conservative monarchs, autocratic presidents, tribal states, failing states, oil-rich states, and water-poor states -- none of which much resemble the sagging bureaucratic communist regimes of Central and Eastern Europe in the late 1980s. Thus, even if the transition process in one or two Arab states does end up bearing some resemblance to what occurred in Central and Eastern Europe, what takes place elsewhere in the region is likely to differ from it fundamentally. Anyone trying to predict the political future of Libya or Yemen, for example, will not get very far by drawing comparisons to the Poland or Hungary of 20 years ago.

"Middle East Transitions Are More Like Sub-Saharan Africa."

Worth considering. Central and Eastern Europe in 1989 is not the only historical analogy political observers are proffering. Some are citing Iran in 1979; others Europe in 1848. A more telling analogy has not been receiving sufficient attention -- the wave of authoritarian collapse and democratic transition that swept through sub-Saharan Africa in the early 1990s. After more than two decades of stultifying strongman rule in sub-Saharan Africa following decolonization, broad-based but loosely organized popular protests spread across the continent, demanding economic and political reforms. Some autocrats, such as Mathieu Kerekou in Benin, fell relatively quickly. Others, like Daniel arap Moi in Kenya, hung on, promising political liberalization and then reconsolidating their positions. Western governments that had long indulged African dictators suddenly found religion on democracy there, threatening to withhold aid from countries whose leaders refused to hold elections. The number of electoral democracies grew rapidly from just three in 1989 to 18 in 1995, and a continent that most political analysts had assumed would indefinitely be autocratic was replete with democratic experiments by the end of the decade.

Of course, like all such analogies, the comparison to today's Middle East is far from exact. The oil-rich Arab states are much wealthier than any African states were in 1990. The significant presence of monarchical systems in the Arab world has no equivalent in sub-Saharan Africa -- as much as delusional "kings" like Swaziland's Mswati III would have it otherwise. The sociopolitical role of Islam in Arab societies is quite different from the role of Islam or other religions in many sub-Saharan African countries. Yet enough political and economic similarities exist to give the analogy as much or more utility than those of Central and Eastern Europe in 1989, Europe in the mid-19th century, and Iran facing Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers. It would behoove policymakers to quickly study up on the sub-Saharan African experience to understand how and why the different outcomes evident on the subcontinent -- shaky democratic success in some cases (Ghana and Benin), authoritarian reconsolidation in others (Cameroon and Togo), and civil war in still others (Democratic Republic of the Congo) -- took place.

"Democracy's Long-Term Chances Are Slim."

Don't give up hope. During the heyday of democracy's global spread in the 1980s and 1990s, democracy enthusiasts tended not to pay much attention to the underlying social, economic, and historical conditions in countries attempting democratic transitions. Democracy appeared to be breaking out in the unlikeliest of places, whether Mongolia, Malawi, or Moldova. The burgeoning community of international democracy activists thought that as long as a critical mass of people within a country believed in and pushed for democracy, unfavorable underlying conditions could be overcome.

Two decades later, democracy enthusiasts are chastened. Democracy's "third wave" produced a very mixed set of outcomes around the world. Many once hopeful transitions, from Russia to Rwanda, have fallen badly short. Given these different results, it has become clear that underlying conditions do have a big impact on democratic success. Five are of special importance: 1) the level of economic development; 2) the degree of concentration of sources of national wealth; 3) the coherence and capability of the state; 4) the presence of identity-based divisions, such as along ethnic, religious, tribal, or clan lines; and 5) the amount of historical experience with political pluralism.

Seen in this light, the Arab world presents a daunting picture. Poverty is widespread; where it is not present, oil dominates. Sunni-Shiite divisions are serious in some countries; tribal tensions haunt others. In a few countries, like Libya, the coherence of basic state institutions has long been shockingly low. In much of the region, there is little historical experience with pluralism. A hard road ahead for democracy is almost certain.

Yet within the political and economic diversity of the Arab world lie some grounds for hope. Tunisia's population is well educated and a real middle class exists. Egypt's protests have shown the potential for cross-sectarian cooperation. Bahrain, Jordan, Kuwait, and Morocco have parliamentary institutions with significant experience in multiparty competition, however attenuated. Additionally, the five factors mentioned above are indicators of likelihood, not preconditions. Their absence only indicates a difficult path, not an impossible one. After all, India failed this five-part test almost completely when it became independent, but has made a good go of democracy. Returning to the analogy of sub-Saharan Africa in the 1990s, at least one-third of African states have made genuine democratic progress despite facing far more daunting underlying conditions.

"Islamists Will Win Big in Free and Fair Elections."

Not necessarily. Many observers watching the events in the Arab world worry that expanding the political choices of Arab citizens will open the floodgates to a cascade of Islamist electoral landslides. They invoke the experience of Islamist victories in Algeria in 1991 and Palestine in 2006 as evidence for their concern.

This fear is overblown. Elections in which Islamists do well grab international attention, but do not represent the norm. Islamist parties have a long history of electoral participation in Muslim countries but usually only gain a small fraction of the vote. In their extensive study of Islamist political participation, published in the April 2010 Journal of Democracy, Charles Kurzman and Ijlal Naqvi find that most Islamist parties win less than 10 percent of the vote in the elections in which they participate.

It is true that after decades of autocracy, secular opposition parties in most Arab societies are weak and Islamists are sometimes the most organized alternative. Yet organization itself does not automatically guarantee electoral success. Given the powerful role of television and the Internet, electoral campaigns have often become as much about mass-media appeal as grassroots work. Especially in new democracies, charismatic candidates leading personalistic organizations and offering vague promises of change sometimes win out over better-organized groups (think President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono of Indonesia). In addition, Islamists may inspire strong loyalty among their core supporters, but winning elections requires appealing to the moderate majority. The protests sweeping the Arab world have so far been notable for their lack of Islamist or sectarian sentiment, and nowhere among the countries in flux is there a charismatic religious leader such as Ayatollah Khomeini ready to seize power.

An Islamist victory somewhere in the Middle East can't be ruled out, but that does not mean we will see a replay of Iran circa 1979. Never in the Arab world have any Islamist election gains resulted in a theocracy, and established Islamist parties across the region have proved willing to work within multiparty systems. Moreover, newly elected Islamists would not have free rein to impose theocracy. Whoever is elected president in Tunisia or Egypt will face mobilized populations with little patience for fresh dictatorial methods as well as secular militaries likely to resist any theocratic impulses.

"Democracy Experts Know How to Help."

Yes, but humility is needed. With all the experience of attempted democratic transitions around the world over the past 25 years, is a clear "transition tool kit" now available to would-be Arab democrats? Western democracy promoters are indeed hurrying to organize seminars and conferences in the region to present lessons learned from other parts of the world. Former activists from Chile, the Philippines, Poland, South Africa, and other new democracies are in demand. Arab activists are eager to learn from the experience of others, and in many cases their hunger for knowledge is intense.

The traveling transition veterans tend to showcase a fairly common set of lessons: Opposition unity is crucial. Constitutional reform should be inclusive. Elections should not be hurried, but also not put off indefinitely. Banning large swaths of the former ruling elite from political life is a mistake. Putting a politically grasping military back in the box should be approached step by step, rather than in one big swoop. Given likely public disenchantment with the fruits of democracy, finding rapid ways to deliver tangible economic benefits is critical.

Such lessons are valid, but the notion of a workable tool kit is dubious. Every Arab country, be it Morocco, Bahrain, or Yemen, has such particular local sociopolitical conditions that supposedly universal lessons will be only suggestive at best. Nostrums about the importance of opposition unity, for example, often derive from countries such as in Chile, Poland, and South Africa, where political opposition movements enjoyed a much higher level of organization and concentration than what exists in the Arab states. Forging unity in a situation like Egypt or Tunisia where mass protest movements draw from dozens of smaller, often informal opposition groups and lack any strong leaders is a very different matter. A six-month wait for elections may be reasonable in some cases, but much too short in others. Moreover, these lessons are often useful more as descriptions of endpoints rather than processes. The hard part -- how to achieve them -- has to be figured out case by case.

"Europe Has a Major Role to Play."

It could. Given its proximity to the Arab world, its welter of diplomatic ties, the weight of its commercial connections, its ample aid budgets, and much else, Europe should be a major player in the region's political evolution. During the last two decades, Europe set up gleaming cooperative frameworks to intensify economic and political ties with the region, including firmly stated principles of democracy and human rights. Yet the first of these, the so-called Barcelona Process, proved to be toothless on democracy and rights. Its successor, French President Nicolas Sarkozy's Union for the Mediterranean, was even weaker.

A whole series of obstacles have inhibited Europe's efforts to turn its value-based intentions into real support for Arab political reform. European leaders fear that political change might produce refugee flows heading north, disruption in oil supplies, and a rise in radical Islamist activity. Traditional French and British ties with nondemocratic Arab elites only add to the mix. The tendency of lowest-common-denominator policies by the consensus-oriented European Union has further undercut efforts to take democracy seriously.

The new fervor for democracy in the Middle East represents an enormous opportunity for Europe to regain credibility in this domain. The European Union played an invaluable role in helping influence the political direction of Central and Eastern Europe after 1989 thanks to the promise of membership for those states meeting certain political and economic standards. The same offer is clearly not possible now, but the core idea should be preserved. Numerous Arab societies badly need reference points and defined trajectories as they try to move away from decades of stagnant autocratic rule. If Europe could reinvigorate its tired and overused concept of neighborhood partnership by offering real incentives on trade, aid, and other fronts to Arab states that respect democratic principles and human rights, it could redeem its past passivity. Brussels appears to be starting to move in this direction -- but follow-through will be the rub.

"The United States Is Now on Democracy's Side."

Not so fast. In his most recent State of the Union address, U.S. President Barack Obama highlighted the success of protests in Tunisia, declaring that "the United States of America stands with the people of Tunisia and supports the democratic aspirations of all people." Then, shortly after Hosni Mubarak stepped down as president of Egypt, Obama pledged that the United States stands "ready to provide whatever assistance is necessary -- and asked for -- to pursue a credible transition to a democracy." On Libya, the United States has joined the many international calls for Muammar al-Qaddafi to leave. Has the United States finally turned the page on its long-standing support for autocratic stability in the Arab world? George W. Bush started to turn that page in 2003 by eloquently declaring that the United States was moving away from its old ways and taking the cause of Arab democracy seriously. But various unsettling events, especially Hamas's coming to power in Palestine in 2006, caused the Bush administration to let the page fall back to its old place.

It is as yet uncertain whether a fundamental change in U.S. policy will occur. The dream of Arab democracy appears to resonate with Obama, and numerous U.S. officials and aid practitioners are burning the candle at both ends to find ways to support the emerging democratic transitions. Yet enduring U.S. interests in the region continue to incline important parts of the Washington policy establishment to hope for stability more than democracy. Concerns over oil supplies undergird a continuing strong attachment to the Persian Gulf monarchies. The need for close cooperation on counterterrorism with many of the region's military and intelligence services fuels enduring ties. Washington's special relationship with Israel prompts fears of democratic openings that could result in populist governments that aggressively play the anti-Israel card.

Given the complex mix of U.S. interests and the probable variety of political outcomes in the region, U.S. policy is unlikely to coalesce around any unified line. A shift in rhetoric in favor of democracy will undoubtedly emerge, but policy on the ground will vary greatly from country to country, embodying inconsistencies that reflect clashing imperatives. Comparing U.S. policies with regard to democracy in the former Soviet Union is instructive: sanctions against and condemnations of the dictator in Belarus, accommodation and even praise for the strongman in Kazakhstan, strenuous efforts at constructive partnership with undemocratic Russia, active engagement in democracy support in Moldova, a live-and-let-live attitude toward autocratic Azerbaijan, and genuine concern over democratic backsliding in Ukraine. A similar salad bar of policy lines toward a changed Middle East is easy to imagine.