Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright

{

"authors": [

"Karim Sadjadpour"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Arab Awakening"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Iran",

"Syria",

"Gulf",

"Levant"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

Source: Getty

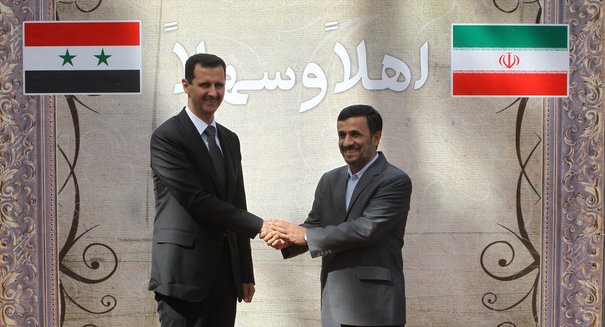

Assad Regime in Syria Crucial to Iran

Iran’s influence in the Middle East is threatened by domestic divisions between Ayatollah Khamenei and President Ahmadinejad as well as the continuing upheaval in Syria, which could undermine Tehran’s principal ally in the region.

Source: Council on Foreign Relations

After months of opposition in Syria to the rule of President Bashar al-Assad, if the Syrian government were to fall “ it would be a tremendous blow to the Iranian regime,” says Iran expert, Karim Sadjadpour. Not only is Syria Iran’s chief regional ally, Syria is the country which allows Iran to supply its “crown jewel” in the Middle East, the Hezbollah movement in Lebanon. He also says that it is unlikely that the comments made by Iran’s foreign minister over the weekend that Syria should take account of the views of the protestors was a serious remark. He says that Iran believes strongly that one should not give in to protestors because to do so “doesn’t alleviate the pressure, it projects weakness and invites even more pressure.”

How is Iran reacting to the upheavals in the Arab world? They’ve been fairly quiet haven’t they?

Initially Iran wholeheartedly embraced the Arab upheavals when it appeared that only U.S.-allied autocracies were at risk, but the uprisings in Syria are hugely concerning to Tehran. The Assad family in Damascus has been Iran’s only regional ally since the 1979 revolution, and if it were to fall it would be a tremendous blow to the Iranian regime. Hezbollah in Lebanon is the crown jewel of the Iranian revolution, and Syria has been the key conduit to Iran’s patronage of it. If the Assad regime were to fall it would make it logistically very difficult for Iran to continue to support Hezbollah the same way it has over the past few decades.

What do you think about the comments over the weekend from the Iranian foreign minister who said that Syria should listen to the protests of its people?

We’re at a loss to know exactly what’s going on, but are there signs that the Iranians are giving tangible support through their intelligence and other security agencies to the Assad regime?

Has anything come of Iran’s efforts to reopen relations with Egypt?

If Egypt maintains its close rapport with the United States—including its strong military alliance–I think it could be some time before Egypt and Iran normalize relations. Another point of contention is the street in Tehran named after Sadat’s assassin, Khalid Islambouli. Egypt has long requested that Iran change the name of that street and Iran has long refused.

On other international issues affecting Iran, what do you think will happen to the American hikers who were recently sentenced to eight years in prison?

It is somewhat reminiscent of the hostages which Iran took not only in 1979, but also the hostage taking in 1980s Lebanon via Hezbollah. It is very difficult for the U.S. government to deal with hostage taking because the concern is that if you release Iranian prisoners in exchange for Americans, you are simply rewarding bad behavior and encouraging hostage taking in the future.

On the internal situation, there are continuing reports of people close to the Supreme Leader Khamenei seeking to get rid of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. How big a split is there in the leadership in Iran?

I thought it was interesting over the weekend that Mehdi Karrubi who was one of the leaders of the opposition to Ahmadinejad in 2009, has been not even seen by his wife for six weeks, and is reportedly been under psychiatric pressure to “confess” to crimes.

Looking at the Iranian opposition and comparing it to the opposition movements elsewhere in the Middle East, I think there is one key distinction. Whereas the opposition movements in places like Syria, Egypt, and Libya have all been seemingly united in wanting to bring down their respective regimes, the Iranian opposition still remains divided about their precise endgame.

People like Moussavi and Karrubi who were participants in the 1979 revolution, and up until 2009 were insiders in the Islamic Republic, still claim that they are seeking a reform of the system. But I think many among Iran’s younger generations would like to see a more dramatic change. I think that’s one reason, among many, why you haven’t seen the protests in Iran snowball like they have elsewhere in the Middle East; the Iranian opposition has yet to coalesce around a common end game.

Do you get the impression if students, if they had their druthers would like a different kind of regime?

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Karim Sadjadpour is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he focuses on Iran and U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East.

- What’s Keeping the Iranian Regime in Power—for NowQ&A

- How Washington and Tehran Are Assessing Their Next StepsQ&A

Aaron David Miller, David Petraeus, Karim Sadjadpour

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

- Duqm at the Crossroads: Oman’s Strategic Port and Its Role in Vision 2040Commentary

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- What We Know About Drone Use in the Iran WarCommentary

Two experts discuss how drone technology is shaping yet another conflict and what the United States can learn from Ukraine.

Steve Feldstein, Dara Massicot

- Beijing Doesn’t Think Like Washington—and the Iran Conflict Shows WhyCommentary

Arguing that Chinese policy is hung on alliances—with imputations of obligation—misses the point.

Evan A. Feigenbaum