Source: Foreign Policy

With grainy photographs of China's new drones and manned stealth fighters trickling onto the Internet every few months, Beijing's rapid military modernization has become a reliable source of anxiety in Western capitals. But there's one area of military technology you've probably never heard of, where a new and potentially dangerous arms race is brewing and where a crisis could touch off rapid and uncontrollable escalation.

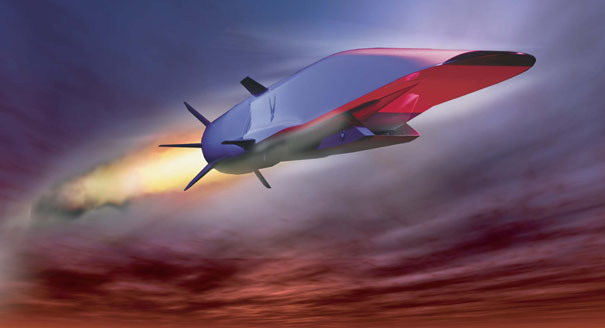

The arena for this contest is the obscure military technology of ultra-fast, long-range -- or boost-glide -- weaponry. Such weapons are designed to be launched -- or "boosted" -- by large rockets. All U.S. tests, for example, have used repurposed long-range ballistic missiles that, in a former life, were used to threaten the Soviet Union with nuclear warheads. But instead of arcing high above the Earth like ballistic missiles, boost-glide weapons re-enter the atmosphere quickly and then glide at incredibly high speeds, potentially for thousands of miles.

It's old news that the United States is currently developing boost-glide weapons as part of the Pentagon's

Conventional Prompt Global Strike program. As originally conceived a decade ago, this program was intended to produce non-nuclear weapons capable of reaching a target anywhere in the world within an hour. The Advanced Hypersonic Weapon, on which the lion's share of funding is currently focused, would not meet this goal. But with a range of roughly 5,000 miles, it would still have a much longer reach than any non-nuclear missile the United States currently possesses.

It now appears that China and Russia are following the United States' lead.

China conducted its first test of a boost-glide weapon, dubbed WU-14 by the U.S. Department of Defense, on Jan. 9. This test was not entirely unexpected. Surveys of the unclassified Chinese technical literature (such as this one by Lora Saalman and this one by Mark Stokes, both of whom are American experts on Chinese military research) reveal that theoretical research into boost-glide weapons has been going on for some time. Still, very little information about the test itself is publicly available. The Chinese government has stated that it took place "in our territory." Elsewhere, it was reported that the missile was launched from Taiyuan Satellite Launch Center in Shanxi province.

If these two claims are correct -- and that's an important caveat -- then together they imply that the total flight distance must have been no more than about 1,800 miles (the distance from Taiyuan to the farthest point still inside China.) The upper end of this range would represent an impressive technological breakthrough. But it is also possible that the WU-14 flew a shorter distance and is simply a souped-up version of its existing anti-ship ballistic missile -- the infamous DF-21D, which has recently sparked concern in the U.S. Navy -- suggesting that the Chinese approach to boost-glide weapons development is evolutionary. In general, the scope and ambition of the Chinese program are unclear, including whether the goal is the delivery of nuclear or non-nuclear warheads -- or both.

As always, Russia wants a piece of the action too. In December 2012, in his annual State of the Nation address, President Vladimir Putin gave a shout-out to the U.S. Conventional Prompt Global Strike program and announced a Russian response that would include future "advanced weapons." Given recent statements from other senior Russian officials explicitly threatening to develop precision-guided weapons systems with "practically global range, if the U.S. does not pull back from its program for creating such missile systems" and evidence of Russian flight tests, such advanced weapons almost certainly include boost-glide systems.

The implications of these developments for stability -- particularly in Northeast Asia -- could be profound. If Beijing decides to field a boost-glide weapon -- and it would probably take at least a decade from now for it to do so -- there is little doubt that its primary target would be U.S. and allied forces. Meanwhile, in a potentially dangerous symmetry, U.S. officials have indicated that they are considering acquiring boost-glide weapons to defeat China's advanced defensive capabilities, including the DF-21D, and its anti-satellite weapons.

So what would the addition of boost-glide weapons mean for a potential showdown with China? On the one hand, fear of U.S. capabilities could deter China from attempting to change the territorial status quo by force. On the other, in the event of a conflict, the existence of boost-glide weapons could make it much harder to manage.

One risk -- practically the only one currently discussed in the United States -- is that, after further developing its early warning capabilities, China might misidentify a Conventional Prompt Global Strike weapon as a nuclear weapon and initiate a nuclear response. But there are other, more likely pathways to escalation that have barely been considered. For example, boost-glide weapons might enable the United States to attack Chinese command and control facilities that are buried too deeply to be threatened by other non-nuclear weapons. However, China reportedly uses the same command and control system for its conventional and nuclear missiles. A U.S. attack on this system for the purpose of disabling Chinese conventional missiles could, therefore, be misinterpreted by Beijing as an attack aimed at suppressing its nuclear capability. Rapid, uncontrollable escalation could result.

But the risks associated with developing boost-glide technology are not purely hypothetical. Even though these weapons do not yet exist, their specter is already influencing the nuclear policies of Russia and China. For example, fear of American conventional weapons has sparked an internal Chinese debate about whether Beijing should abandon its long-standing policy not to use nuclear weapons first.

Meanwhile, various Russian officials have repeatedly indicated a lack of interest in negotiating further nuclear reductions because they worry that doing so would make their nuclear forces more vulnerable to American conventional weaponry. In fact, this fear is actually leading Russia to diversify -- not contract -- its nuclear forces. In December 2013, the Russian military announced that it would start work on designing a new rail-mounted nuclear missile as a direct response to Conventional Prompt Global Strike.

These dynamics present Washington with a complex policy problem that has no obvious solutions. While halting the Conventional Prompt Global Strike program would mitigate some risks, it could also enhance others if these weapons turn out to have a unique ability to prosecute key military missions.

Perhaps the only thing that's clear is that ignoring the problem isn't going to make it go away. For this reason, it's deeply worrying that boost-glide weapons are being developed with minimal public or congressional scrutiny in the United States, and with no scrutiny in Russia or China. It's equally worrying that these weapons are not being discussed at a governmental level in either Sino-American or Russian-U.S. dialogues (non-nuclear boost-glide weapons, moreover, don't fall under any existing treaties). The implications of these weapons should be seriously considered now -- not after they're fielded. Their implications for international security -- particularly in the event of a U.S.-China conflict -- are simply too profound to leave the debate to the handful of wonks that have heard of them today.

This article was originally published in Foreign Policy.