If you weren’t paying close attention, you might have missed the gentle mocking tone during Vladimir Putin’s meeting with John Kerry in the Kremlin on December 15. “We can’t keep up with your movements. You need some sleep, I can see that,” suggested Putin. (Translation: “You are tired, Mr. World Policeman. You’re learning that you can’t do it all by yourself. Go get some rest. Maybe I can help you out.”)

Then the Russian president twisted the knife, just in case any advocates of punishing and isolating Moscow needed to be reminded that Obama was now actively soliciting help from his longtime nemesis. “Together, we are looking for resolutions for the most serious of crises,” Putin continued.

The practical results of this newfound spirit of Russian-American cooperation were announced just three days later at the UN Security Council, when Moscow supported UNSCR 2254, a U.S. -sponsored initiative for political transition in Syria.

The contortions from U.S. policymakers were painful to watch. After finishing a stroll down Moscow’s famed Arbat pedestrian street, capped by interactions with the quintessential man on the street, Kerry grandly announced that Washington “[doesn’t] seek to isolate Russia.” It didn’t take long for the White House to walk that one back. On the eve of Kerry’s visit to Moscow, White House Press Secretary Josh Earnest insisted that nothing had changed and that Russia is isolated from the rest of the international community.

Western policy toward Russia has often been divided into two camps. The first holds that the world will be more secure only if the West takes an extremely tough, unyielding stance. The other camp maintains that frank dialogue and diplomatic engagement can bring benefits without compromising on principles. Members of the latter camp talk to Russia like they would to someone in a fit of rage or someone about to take leave of one’s senses.

Yet today Russia is clearly less isolated than it was 12 months ago. Although Kerry’s visit to Sochi in May took the world by surprise, Lavrov and Kerry often communicate several times per month or even per week, and Putin and Obama have had three substantive conversations in the past three months. Considering the events of the last two years, this is remarkable.

This new surge in bilateral communication would be happening without the Russian intervention in Syria. The intervention appears have a number of goals, one of which is just to have some target practice, according to a rather careless admission Putin made to journalists. But there’s no mistaking that the Syrian operation allowed the Kremlin to preserve some of the dividends the Russian regime scored at home over the last two years and to cut its reputational losses abroad. This move tries to draw a line under the triumphant conquest of Crimea and shift Russian public attention away from the messy outcome in eastern Ukraine. With Russia in the grip of an economic crisis, it’s not a bad thing for the conversation to shift to exotic locales in the Middle East. But the regime has spared no effort in trying to portray the Syrian military campaign as an illustration of Russia’s ability to stand up to the United States and undermine the now-discredited suggestion that “Assad must go.”

Staying Relevant

Those who think that entering Syria was a way for Russia to separate from the West and isolate itself are wrong. Russia doesn’t see itself in a cocoon; being a butterfly is much more enticing. Yet those who think that Russia is there to make peace with the West and rejoin it are also wrong.

The idea was to come back on Moscow’s terms to the top table where big global issues are discussed—not as a junior ally, but as a “partner.”

Putin and other Russian officials always pronounce the word “partner” with considerable irony, the same irony that could be read in the Russian president’s suggestion that John Kerry should “get some sleep.”

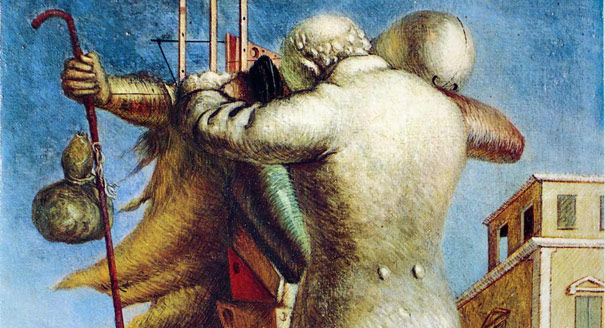

The Syrian campaign was the regime’s attempt to retain the domestic prestige it won with the annexation of Crimea and to break out of the external siege that was laid by the West immediately afterwards. And, as outmoded as it may sound, the Kremlin still believes that it can create a global order where the mighty and the powerful can cut deals over the heads of the little guys and establish their tidy little spheres of influence. Russia is making a dash alright, but it’s a dash to the past, to the way Europe looked one hundred years ago, on the eve of World War I.

Those who think that entering Syria was a way for the Kremlin to further rupture ties with the West are misguided. But so are those who think that Russia is in Syria to make peace with the West and move toward joining it.

The goal was to return to the club where the destiny of the world is being discussed, not as an ally (because given the current economic disparity, one could only be a junior, subordinate ally) but as a “partner”—a word that is invariably spoken in Russia with phonetic quotation marks: a disobedient, sometimes blunt neighbor with whom considerations of the world order must be shared.

Russia doesn’t want to join the West (it would have to change to be accepted there). Instead, it is trying to fit into the new global order where powerful nations make deals, join short-lived alliances, and establish spheres of influence. It is a race to the past, when this sort of geopolitics predominated; it is a return to Europe on the eve of World War I.

At the same time, refusing to cooperate won’t work. To earn its seat on the world’s board of directors, Russia has to be constructive. In particular, it has to be willing to discuss Assad’s departure. That’s precisely what happened when Russia supported the U.S.-sponsored UNSCR 2254, which was unanimously adopted on December 18.

By supporting the resolution, Russia agreed to the start of negotiations in January 2016 on the formation of a “transitional governing body with full executive powers” in Syria. It also agreed to support a new draft constitution and elections that will include Syrians now residing abroad.

Russian diplomats are being honest when assuring the public that their goal is not to save Assad personally. Rather, their goal is to save face—they are against any humiliating regime change. Assad may go, but will do so only with dignity. He won’t be killed, convicted, or extradited to stand trial in The Hague. There will be no occupation of Damascus or cleansing of the Alawites and Baath Party elements at the hands of some group of moderate Islamists. The ministries and state institutions will continue their normal work, and the big bosses will depart peacefully rather than have to flee in the middle of the night.

The resolution mentions “ensuring the continuity of governmental institutions” twice and calls for combating terrorist acts committed by ISIS, Al-Nusra Front, Al-Qaeda, and other terrorist groups. A Jordanian-led process is supposed to work out an agreed list of terrorist groups, an effort that could retroactively exculpate Moscow for bombing so many of them.

Of course, this arrangement may still fall apart, since the heart of the resolution is focused on creating a ceasefire, which will involve all hostile parties except for ISIS. But how can there be a ceasefire when one of the most important parties doesn’t want it? Eventually, those who don’t agree to take part in negotiations will be equated with terrorists, and those who are willing to negotiate will be considered legitimate forces.

Yet make no mistake about Russia’s actual yardstick for success: the Russian military gambit in Syria will be considered successful only if it reduces tensions with the West. Putin himself spilled the beans about that. “I’m going to tell you an important thing now. We are supporting the initiative of the United States, including the preparation of a UN Security Council resolution on Syria; in fact, the Secretary of State brought the proposed resolution on this visit,” Putin admitted at a press conference.

The Kremlin approved the U.S. proposal because Kerry gave the Russian leaders a real New Year’s gift. Their dreams finally came true: the Americans consulted Russia before making a decision. They showed Russia some respect and got what they wanted in return.