Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

{

"authors": [

"Alexander Gabuev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

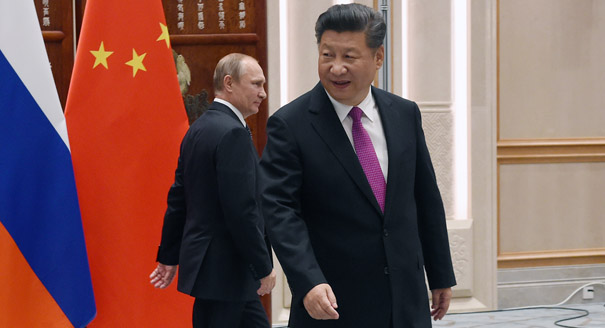

Though it serves to gain from greater engagement in the Asia-Pacific, Russia’s policy toward the region has been highly inconsistent. Why doesn’t Putin attend the East Asia Summit or participate in other important regional initiatives?

Although Russia provided some evidence at the recent Eastern Economic Forum (EEF) in Vladivostok that its “pivot to the East” is working, the Kremlin’s Asia-Pacific policy remains highly inconsistent. Why is the Kremlin eager to engage in some arenas but comfortable taking a backseat in others? Why, for example, did Moscow choose to ignore the East Asia Summit (EAS), held in Laos just three days after the EEF?

Vladimir Putin attended the EAS when it first convened in Kuala Lumpur eleven years ago and actively lobbied for Russia’s inclusion in the region’s developing security lattice. But Russia wasn’t sufficiently involved in Asian affairs at the time and its trade with the Asia-Pacific was miniscule, so it wasn’t officially admitted to the forum.

Russia became a member only in 2011, at the same time as the United States. The forum’s organizers wanted to invite all influential players to join in order to make the EAS into an Asian OSCE—a platform allowing East and West to establish rules aimed at keeping the region out of a large-scale military confrontation.

Russia was accepted without preconditions because of its status as a permanent member of the UN Security Council and because two-thirds of its territory lies in Asia. Russia joined shortly after it announced its pivot to the East: the ASEAN countries hoped that Russia would become an independent power center with a positive agenda, acting as a counterweight to China and the United States.

But Moscow quickly showed that it didn’t care much about its role in the forum: the Russian president hasn’t visited a single EAS summit since his country joined.

Symbolism and personal involvement are extremely important in Asia; Putin’s perpetual absence at the region’s key security summit says much more than any official statement about his country’s pivot to the East. All the more so because the Asia-Pacific countries know that Putin is the only foreign policy decisionmaker in Russia.

Putin’s absence is particularly noteworthy because of Barack Obama’s consistent attendance: Putin’s American counterpart missed the EAS just once—during the federal government shutdown in 2013.

After six no-shows, Asian diplomats see the Russian president’s absence as a given; Russian promises to pay more attention to the EAS made at the Russia-ASEAN Summit in May were rightly met with considerable skepticism.

Russian officials offer several explanations for their absence. First, they claim that Russia is focused on the Asian economy rather than its security, which is an arena of U.S.-China competition.

Second, Putin is known to dislike group discussions “about nothing” and attends the G20 and APEC summits for the sake of bilateral talks. Since he is already in contact with key Asian heads of state, he sees no point in flying to the EAS for yet another meeting.

Third, Russia can promise no game-changing security agenda to the Asia-Pacific countries at the moment. Why should Putin go if he has nothing to offer?

Finally, the EAS is still a relatively new forum, so Russian officials feel confident that their president isn’t missing out on anything critical.

It’s a hard and often thankless task to convince Putin to change his mind, and no one’s trying to right now. This is a shame, as the Russian president’s participation in the EAS would be both symbolically and practically important for Russia’s Asia-Pacific policy.

Putin’s regular attendance at the most representative Asia-Pacific forum would emphasize the seriousness of Russia’s intentions in Asia. Of course, his mere presence won’t replace a full-fledged administrative effort to establish ties in the region and develop the Far East, but it could make Russian promises more credible in the eyes of Asian politicians and business leaders.

Unlike Russia, China can afford to send its prime minister rather than its head of state to the EAS: Li Keqiang can deflect questions about his country’s behavior in the South China Sea by saying that they are beyond his expertise. With China being the economic center for the entire region, he can instead talk about the benefits of trade.

Though Russia is seen as an important political and military player in the Asia-Pacific, Putin’s persistent snubs tarnish Russia’s reputation as an independent actor, especially in light of the Russian-Chinese joint military exercises in the South China Sea and the Russian president’s statements in support of Beijing’s refusal to accept The Hague arbitration rulings on the region.

Perhaps most importantly, Russia has a serious stake in being a rule-maker in the Asia-Pacific. Military stability in the region is a guarantee of economic growth and therefore a necessary condition for Russia’s successful pivot to the East.

Speaking at Asian Society recently, Hillary Clinton’s close advisor Jake Sullivan mentioned that the Clinton team intends to turn the EAS into a platform for codifying security norms in the Asia-Pacific. Beijing increasingly talks of China’s need to discuss the issue, which will necessitate Xi Jinping’s attendance at the EAS.

Moscow should join this conversation sooner rather than later. The Kremlin actually has things to say, after all: Russia is the only country to have been able to agree on a code of conduct with the United States and its allies. The Asia-Pacific has a long way to go on this front.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

A recent offensive by Damascus and the Kurds’abandonment by Arab allies have left a sense of betrayal.

Wladimir van Wilgenburg

Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán faces his most serious challenge yet in the April 2026 parliamentary elections. All of Europe should monitor the Fidesz campaign: It will use unprecedented methods of electoral manipulation to secure victory and maintain power.

Zsuzsanna Szelényi

The supposed threats from China and Russia pose far less of a danger to both Greenland and the Arctic than the prospect of an unscrupulous takeover of the island.

Andrei Dagaev

There is an urgent need to strengthen the relevant international legal frameworks if they are to protect against threats to use nuclear weapons.

Anna Hood, Monique Cormier