The coalition for President Vladimir Putin’s third term wasn’t built as a coalition of war, but became one due to the events that transpired, and due to its own paradoxical nature. Five years ago, the key stakeholders of this coalition could have fit into a large conference room. And yet it was this coalition that played a role in the street-level and mass support for the president.

In the fall of 2008, when the coalition was designed, it was planned as a short-term PR project, not a political initiative that was to change Russia forever. In July 2008, as the financial crisis took hold in the United States, Russia’s oligarchs—oil executives, steelmakers, retailers, and industrialists—had started asking the government for support. Oil prices and the ruble were falling in tandem, and people in the government were growing nervous. In October, the crisis suddenly took on a social dimension: the country’s large corporations started threatening the government with mass layoffs.

Putin’s position was complicated. Having swapped jobs with Dmitry Medvedev to become prime minister, he was responsible for Russia’s economy, not the president. Putin didn’t know when the crisis would end, or at least where falling oil prices would land. He didn’t know how long he would be able to continue offering support. In order to lessen the uncertainty, to narrow the gap between expectations and reality, to win some time, he needed to bluff—but with style. He needed PR.

In October 2008, the Kremlin’s main spin doctor—the number one deputy head of the presidential administration, Vladislav Surkov—started working on an anti-crisis information program, not as a political agenda, but as an ideological product. The document prepared by Surkov was never widely publicized, but the whole country has long known what it contained. Everything is evident from the names of the document’s sections alone: “The Horrors of the West,” “A Historic Opportunity,” “The Social Responsibility of Business,” etc. The contours of the ideological revolution, usually dated to 2012 or 2014, were in fact outlined back in 2008.

The plan was titled “The Anti-Crisis Information Campaign.” It contained several revolutionary ideas. First of all, to constitute the core of Putin’s anti-crisis coalition, Surkov invented a new middle class, which hadn’t really existed before then. This was a patriotic, anti-Western middle class, made up of office workers and employees of the government and private factories, as well as entrepreneurs working in the private sector: primarily small business owners, but also oligarchs.

The plan was a rejection of pact-based interrelations with the country’s citizenry and a transition to a contractual relationship with selected social groups. Each member of the new Putin coalition, in Surkov’s mind, would receive an articulate collection of promises from the state. The industrial workers needed to be promised continual demand for their products, government contracts, social housing, and government oversight of employers’ social responsibility. Entrepreneurs would be promised financial flow (cheap loans and the purchase of business debts from foreign banks), forced loyalty between banks and business, and special terms for government contracts. The office worker would get cheap mortgages, consumer loans, and some “new opportunities.”

The third revolutionary idea was a total reconceptualization of Russia’s relationship with the EU and the United States. In Surkov’s plan, the origins of the crisis would lie with some sort of aggregated “West,” and the crisis itself would be framed as the West’s punishment for its sins. The previous world order had come to an end and a new world order would be created by Russia, obviously. “While the Western mindset sinks into depression from the shock, our country, which has experience from past crises and which is much more stable under global stress, has a chance to become the most dependable financial-economic system,” Surkov’s program promised. “This is Russia’s chance for leadership in the world economy.”

Surkov sent the anti-crisis plan to Medvedev and Putin in early November 2008. In March 2009, the administration confirmed an anti-crisis program that increased government spending by 3 trillion rubles ($52 billion at today’s exchange rate), and bureaucrats had to literally do the impossible: create the nonexistent, patriotic middle class that Surkov described. It was an unimaginable alliance of workers, state employees, and capitalists whose economic interests did not always coincide.

The rules of the game had to change, and they did: Businessmen moderated their appetites regarding commercial viability of production, and didn’t lower wages or engage in mass layoffs. In exchange, they received cheap loans from government banks worth billions of rubles. With this money, they swallowed up smaller business competitors who didn’t have access to the anti-crisis trough. Workers didn’t protest or demand better conditions or a change in ineffective proprietors because they weren’t being fired and the bosses were getting government support.

In some ways, the anti-crisis measures instituted during 2009–2011 resembled a collection of economic and social prosthetics. Natural economic conditions for businesses and workers changed. Losing things in one area, social groups that benefited from anti-crisis support got their help from the government in other places. This is what today in Russia is called the “public-private partnership” and the “social responsibility of business.” In giving up on economic logic, businesses and individuals start to follow a quasi-political logic. Motivations change. Instead of defending their own economic interests, they start to compete over the amount of money and preferential treatment provided to them by the government.

The recipients of anti-crisis support have formed the face of the new majority, the coalition that supports Putin. The representatives of the labor collectives that supported Putin in 2012 could have fit into a modestly sized ballroom, but the political responsibilities that they took on forced them to exert pressure on those they represented. The framework for pro-regime and pro-Putin mass rallies was formed not so much by state employees as by workers of the enterprises that Putin’s administration had favored, saved, and supported.

That’s how the new Putin majority turned into a “street” majority. The unexpected resource that the Kremlin acquired—the opportunity to engage in mass politics—became an important trump card for the regime in 2014. The much-touted figure of 86 percent approval ratings for Putin was born not only thanks to the annexation of Crimea, but also because of the money that Putin’s administration spent in the late 2000s to fight the financial crisis.

At what point did the coalition of wealthy representatives of labor collectives turn into a coalition of war? From 2012, war was expected everywhere: in the government and among business leaders who would support the continuation of anti-crisis measures at any cost. But what were these measures?

Protectionism. The replacement of foreign capital with affordable and quasi-affordable investments, which, after several years of government collaboration, were much easier to receive than foreign investments. The growth of government contracts and, in general, the growth of any non-market demand. Import limitations. All of these measures were experimented with between 2009 and 2010, and all of these measures were introduced in 2014.

In the summer of 2012, everything was heading for either crisis or war. It turned out that the economy was much better at surviving oil price drops and the cessation of foreign capital influx. There were fewer Western investments on banks’ balance sheets than in 2008; Western-held debt was much lower; and currency reserves had been restored.

The only thing that Economic Development Minister Andrei Belousov warned the prime minister and president against was supporting the ruble. There was no need to repeat 2008, to spend hundreds of billions of dollars on controlled devaluation. This advice turned out to be useful at the end of 2014. The ruble fell, the Central Bank washed its hands of the situation, but nobody took to the streets and squares of Russian cities. The devaluation even eased problems in the economy, which had been choked by Western sanctions and falling oil prices.

What was left were mere details. At the start of 2013, Putin ended the sale of strategic Russian assets to foreign investors. Russia doesn’t need Western investors meddling in strategic branches of the economy: if the budget needs money for privatization, government-run giants can take care of everything. And that’s exactly what happened in 2016: a portion of the governmental shares in the oil firm Rosneft was sold, brokered by the Russian government bank VTB to a group of investors. Part of the deal was paid for with a loan from another large Russian bank affiliated with the government.

At the end of 2013, the dogs of war were officially let loose with an amendment to the Russian criminal code introduced to the parliament by the president himself. The gist of the amendment was that if a Russian fights on the territory of a foreign nation in an illegal armed formation, but the interests of the war coincide with national interests, nobody is going to put the combatant on trial at home.

In history, the causes rarely contain all of their consequences. The 2014 war in Ukraine became possible due to the governmentalizing of the economy during the 2008 crisis. But these actions didn’t anticipate war. The manual control of the Russian economy formed to fight the crisis became an important component in fighting sanctions, and even in equipping the Donbas. But it was initially planned for different needs.

When, in 2009, the Russian government was canceling debts owed by defense companies to budget and insurance funds, nobody could have imagined that eight years later, these enterprises would turn Syria or eastern Ukraine into a testing ground for demonstrating their technical accomplishments and production abilities. But it was these resolutions that led to an increase in defense spending and the militarization of the country’s budget.

The parade of loyalty from big business enjoyed by the Kremlin in 2014 would have been impossible if the business owners owed the West instead of Putin and the largest Russian government banks. By giving loans to oligarchs, Putin had guaranteed the loyalty of the wealthiest Russians.

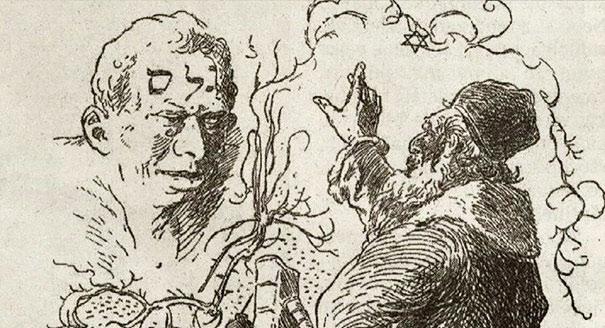

Almost by accident, and seemingly without any long-term plans, Putin brought to life a golem—an animated mud giant—in the form of a coalition of the overwhelming majority. This majority was, and remains, in a state of continual reformation, renewal, and reconstruction. It is a project that is being realized in space and time, for money.

There are various endings to the story of the golem. According to some, the mud creature kills its creator. But there are others, in which after completing its intended task, the golem crumbles to ashes, returning to its natural state. Only one thing is clear. The radical social experiment created by Putin will one day end. The “Putin majority,” in whose name the Russian elite operate, and which seems monolithic, will be released from the burden of its responsibilities. It will crack into several different social groups. The coalition of war will cease to exist. It will step down and make room—but for whom? Perhaps, for a coalition of peace?