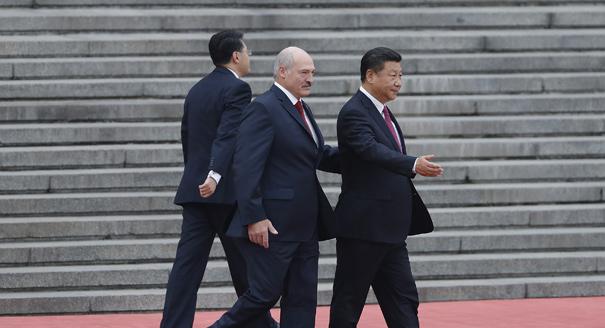

For Lukashenko, Chinese President Xi Jinping’s August 10 message congratulating the Belarusian leader on his victory in the previous day’s presidential election was the best gift for which he could have asked. The support of the world’s second largest economy was highly welcome, since Belarus’s post-election crisis was making Lukashenko increasingly dependent on Russia, much to his chagrin.

Ideally, the Belarusian president would like to not only balance East and West but also exploit the divisions between Moscow and Beijing. But there are few such divisions, with China’s efforts to expand its presence in Eastern Europe, including Belarus, designed to avert a clash with Russia.

Belarus’s cooperation with China has always been informed by its relations with Russia and the West. Hence the original impetus for Minsk’s pursuit of a closer Sino-Belarusian relationship: the 2000s’ oil wars with the Kremlin and EU sanctions.

In 2005, Lukashenko told Xinhua, China’s official news agency, the reason for his newfound attraction to Beijing: “So long as we [Belarus] develop such relations with China, we cannot be isolated.” That same year, he paid a state visit to the PRC, returning with a stack of memoranda and a mountain of promises.

Sino-Belarusian trade began to grow, increasing from more than $180 million in 2000 to $2 billion in 2008. In 2005, Belarus appeared for the first time in a Chinese Foreign Trade and Economic Cooperation Ministry report on outward direct investment, and by the end of the decade, Chinese investments in Belarus’s economy totaled $24 million.

A similar trajectory was taken at the turn of the century by China and Central Asia. But unlike the states of Central Asia—which neighbor China and, as exporters of natural resources, have something to offer that major importer of natural resources—Belarus is far from China’s borders, while its small internal market and lack of significant reserves of natural resources seriously limit the prospects for Sino-Belarusian cooperation.

If in the 2000s it was Belarus that made the first move, in the 2010s China’s interest in Eastern Europe was awakened by the global financial crisis. Hitherto preoccupied with increasing production and focused in its economic diplomacy on natural-resource-rich countries, Beijing found Western demand for Chinese production in decline and set out not to let its factories stand idle given the implications for internal stability. China was forced to look for new markets, a search that led to the Belt and Road Initiative and coincided with a massive economic crisis in Belarus.

Although China’s role in the Belarusian economy has gradually increased since then, Beijing cannot, and has no intention to, seriously compete with Moscow. China may be Belarus’s third largest trading partner, but its share of the latter’s total trade in January–June 2020 numbered just 7 percent, in contrast to Russia’s 48.5 percent.

According to Belarusian Finance Ministry figures, since 2013, Belarus has attracted $3.6 billion, $10.8 billion, and $2.6 billion in loans from China, Russia, and the EBRD, respectively.

China’s economic interests in Belarus do not intersect with Russia’s. Whereas Russian state companies seek to participate in the privatization of large enterprises like MAZ and MZKT, having already privatized the gas transportation system, the Chinese are more interested in small plants. Large-scale projects are built from scratch using China’s own technologies, while Belarus, like other developing economies, is predominantly offered “tied” loans by China.

All in all, there is no reason why Russia and China should be seriously at odds or in serious competition in Belarus. Moscow fully understands the game Lukashenko is playing with Beijing, sees no big threat to itself in his efforts, and so makes no attempt to put a spoke in the wheel.

Russia’s leadership views China’s strengthening position in Eastern Europe, including Belarus, through the prism of its confrontation with the West. China’s expanding presence provides the region’s countries with an alternative to the EU. Meanwhile, Moscow and Beijing reach understandings among themselves and occasionally even coordinate their actions.

Besides, most Chinese projects in Belarus fall short of expectations, while even successful ones are not without flaws.

Even so, Lukashenko tries hard to show Beijing how much he cares about his country’s relations with China and his own relationship with the Chinese Communist Party’s general secretary, although his efforts do not change the fact that one cannot speak of Chinese business’s serious interest in the Belarusian economy or of Chinese society’s interest in Belarus and events there.

Tellingly, even though the average daily number of Belarus-related search queries on Baidu, China’s most popular search engine, increased by 395 percent in August 2020, “how does Belarus differ from Russia?” remained the top search query before Alexander Lukashenko appeared for the second time publicly wearing body armor and holding an automatic rifle.

When Belarus’s post-election protests first broke out, the Chinese press covered them dryly and with little detail, owing to the sensitive nature of the topic of demonstrations. On August 10, news outlets reported only that Lukashenko was reelected with 80 percent of the vote. The following day, Xi’s message of congratulations was covered on the front page of the People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Communist Party of China.

Pengpai, or the Paper—a Shanghai United Media Group-published online newspaper allowed to operate with relative freedom—reported on the protests yet cited only Belarus’s Interior Ministry as a source. Other news outlets devoted coverage to pro-Lukashenko rallies, with the Shanghai Media Group-owned Dragon Television passing protesters photographed carrying white-red-white flags, as well as posters reading “a killer cannot be president,” off as government supporters.

As the protests have gained momentum, the press has paid them more and more attention. But Chinese news outlets continue to confine themselves to citing Lukashenko’s official statements, the comments of Vladimir Putin and the Russian Foreign Ministry, and Russian state media coverage.

The statements of Chinese officials have been equally delicate. In lending themselves to countless interpretations, they have brought to mind how Chinese diplomats reacted to questions about the status of Crimea after its annexation by Russia—in a way that struck whoever was listening as an affirmation of their own position.

Beijing sees no point in openly backing one side or the other in Belarus’s political crisis given the situation’s uncertainty. In any case, China simply has no real means of influencing events in Belarus. Hence its adoption of the highly reliable tactic of avoiding loud statements and leaving the action to Russia, which has more instruments of influence and for which the stakes are higher.

To be sure, Beijing finds working with Lukashenko easy. Should he manage to remain in power, it will continue to deepen relations with Minsk. But if he is ousted, China will search for a common language with whoever replaces him. A Lukashenko successor, for their part, will not have the option of ignoring a partner like the PRC, which Belarus needs much more than China needs Belarus.