Nikita Smagin

{

"authors": [

"Nikita Smagin"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

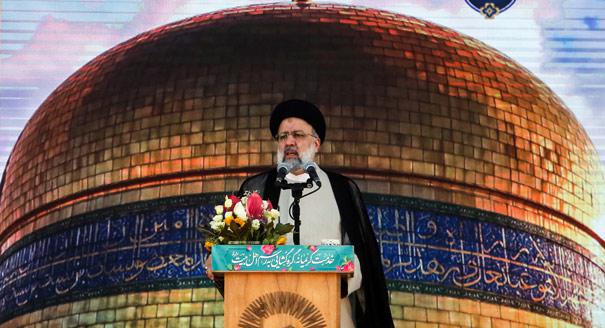

Conservatives Triumph in Tehran: Does the Iran Nuclear Deal Still Matter?

The Iran nuclear deal is important not just because of what it achieves, but also as a model for potential future agreements. It tests an approach whereby the United States concludes an agreement with a rogue state, while the implementation of that agreement is secured by a multilateral format.

Signed in 2015, the Iran nuclear deal remains a key international concern. After former U.S. president Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the deal, Iran wound up in a deep economic crisis instead of benefitting from the promised boom of Western investment. As a result, those in the Iranian elite who had supported reforms and dialogue with the West lost their clout, and an anti-Western conservative, Ebrahim Raisi, won the June 18 presidential election.

Yet the deal remains valuable for both Iran and the world community. For Tehran, it is the simplest way to stabilize the domestic situation and maintain power. For the world at large, it is the only means of making Iran a more predictable and responsible participant in global affairs.

The Iranian authorities have always relied on elections to legitimize the political system and viewed voter turnout as a key metric, even applying administrative pressure to bring people to the polls. Individuals who don’t vote can be turned down for government jobs, for example.

Even without this administrative pressure, turnout in Iranian elections was traditionally high because there was genuine competition among candidates and votes actually mattered. However, this year saw the first presidential election in a quarter-century with no question of who would win.

Above all, this reflected the deep crisis in the reform camp. After the United States withdrew from the nuclear deal and sanctions were reinstated, the liberals in the Iranian ruling elite who had called for normalizing relations with the West lost all public support. Many Iranians still want liberalization and better relations with the rest of the world, but they no longer trust the in-system politicians who had promised them this. Outgoing president Hassan Rouhani personifies this lost trust.

The conservatives have capitalized on these dynamics to seize all levers of power. In the February 2020 parliamentary elections, very few alternative candidates were allowed onto the ballot, and ultimately the hard-liners won about 90 percent of the seats. In the presidential election, the Guardian Council, which oversees elections, approved seven candidates, only two of whom were reformers, both weak figures with no chances of winning.

Most importantly, the liberal segment of society has been apathetic about the exclusion of reform candidates from parliamentary and presidential elections. The 2021 presidential election had the lowest turnout in history at 49 percent, and Raisi won with 62 percent in the first round. Iranians who favor reforms and openness, primarily residents of major cities, mostly skipped the elections. Second place went to voided ballots, which accounted for 4 million out of the 29 million ballots cast. (Iranian ballots do not offer an “against all” option.)

Because of this low turnout, the new president will need to find other sources of legitimacy. The most reliable of these would be improving living standards, which will be impossible without reducing international pressure on Iran. The nuclear deal is therefore crucial for the regime, regardless of Raisi’s political views and rhetoric. It is the only means of ensuring economic growth and healthy national development. This is why in his very first press conference, Raisi said that Tehran will abide by the terms of the nuclear deal provided that other participants comply with their obligations.

The consolidation of power by conservatives doesn’t necessarily mean that Tehran’s foreign policy will become more radical. The current ruling elite is, above all, pragmatic. It has left the 1980s ideals of “exporting the revolution” far behind. What Iran really wants today is to protect itself in the face of hostility from the United States and a number of regional powers. Tehran sees its missile and nuclear programs and its support of non-state actors in the Middle East as the sources of its security.

At the same time, this doesn’t mean that Iran’s partners in the nuclear deal can relax and count on Tehran returning to the deal under any terms. The election of a conservative president increases the risks that Tehran will become an autarky, close itself off, and begin making decisions following a logic that is foreign and incomprehensible to other states. Considering Iran’s significant influence and presence in the region, this could have grave consequences for much of the world.

The West therefore needs the nuclear deal as the only effective means of making Iran more predictable. The agreement creates financial levers that can contain Tehran’s actions; draw it into the international community; and compel it to conduct a dialogue with the West, including the United States. A sanctions-free Iran has something to lose. Otherwise, the only way to contain Tehran is through military actions that could bring the entire Middle East to the brink of disaster.

For Russia, the nuclear deal might not seem as crucial, since Moscow and Tehran have other channels of cooperation, including joint operations in Syria, negotiations in the Caspian region, and the establishment of the North–South transportation corridor. Yet Moscow cannot ignore an opportunity to turn Tehran into a more predictable partner.

If the stifling sanctions are maintained, this will inevitably lead to Iran’s technological and institutional degradation and run the risk of a large-scale crisis, with potential water and electricity shortages, infrastructure deterioration, failures in social support systems, corruption, domestic instability, and more.

In that scenario, the Iranian political elite may become more fearful of its adversaries, feel cornered, and focus on developing nuclear weapons. A weak and unstable country with a nuclear bomb is a much greater risk than a predictable, albeit peculiar, state with a supervised nuclear program.

Finally, the Iran nuclear deal is important not just because of what it achieves, but also as a model for potential future agreements. It tests an approach whereby the United States concludes an agreement with a rogue state, while the implementation of this agreement is secured by a multilateral format. The fact that the United States left the deal because of its own domestic politics and now wants to return only makes this model more pertinent. Trump’s actions showed that the United States has enough sway to unilaterally block the implementation of the deal. However, the multilateral format kept the deal from falling apart.

The Iran nuclear deal also offers an answer to the question of what a path toward de-escalation and the removal of sanctions could look like. Lately, sanctions have become a popular instrument in international relations. However, for many states, particularly in the West, sanctions, once imposed, are driven more by domestic politics than by international realities. It is easy to expand and reinstate sanctions, but difficult to lift them, even if the target state changes its course. Today, the sanctions mechanism seems to be applied in one direction only.

The Iran nuclear deal offers a promising precedent: a rare example of a state resolving to make concessions to the global community, and having sanctions lifted in exchange. If it can become a reality, this precedent may see great demand.

This article was published as part of the “Relaunching U.S.-Russia Dialogue on Global Challenges: The Role of the Next Generation” project, implemented in cooperation with the U.S. Embassy to Russia. The opinions, findings, and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the U.S. Embassy to Russia.

About the Author

Nikita Smagin

Expert on Iranian foreign and domestic policies, Islamism, and Russia's policy in the Middle East

- What Does War in the Middle East Mean for Russia–Iran Ties?Commentary

- How Far Can Russian Arms Help Iran?Commentary

Nikita Smagin

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The U.S. Risks Much, but Gains Little, with IranCommentary

In an interview, Hassan Mneimneh discusses the ongoing conflict and the myriad miscalculations characterizing it.

Michael Young

- When Do Mass Protests Topple Autocrats?Commentary

The recent record of citizen uprisings in autocracies spells caution for the hope that a new wave of Iranian protests may break the regime’s hold on power.

Thomas Carothers, McKenzie Carrier

- The Greatest Dangers May Lie AheadCommentary

In an interview, Nicole Grajewski discusses the military dimension of the U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran.

Michael Young

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

- Why Are China and Russia Not Rushing to Help Iran?Commentary

Most of Moscow’s military resources are tied up in Ukraine, while Beijing’s foreign policy prioritizes economic ties and avoids direct conflict.

Alexander Gabuev, Temur Umarov