Minxin Pei

{

"authors": [

"Minxin Pei"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "asia",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "AP",

"programs": [

"Asia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"East Asia",

"China"

],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

China’s Money Diplomacy Hits Limit

While China's economic resilience after the financial crisis has boosted its confidence, it has also led to a diplomatic assertiveness that ultimately weakens its strategic credibility in Asia.

Source: The Diplomat

One of the most interesting features of Chinese foreign policy is its use of commercial deals to cement strategic relations with countries around the world. Indeed, the Chinese government, often relying on deep-pocketed state-owned banks and firms, has greatly expanded Beijing’s economic influence across the globe.

These days when senior Chinese leaders go abroad, they routinely bring with them a large retinue of businessmen (mostly executives in state-owned companies) to sign headline-grabbing contracts with host countries. For example, during Premier Wen Jiabao’s recent visit to India and Pakistan, tens of billions of trade and investment deals were announced.

China’s hyperactive use of commerce to advance its national interests is driven by several factors. For one, the debt crisis in Europe and high unemployment in the United States have given cash-rich China greater competitive advantages and ample opportunity to expand its economic influence abound in the post-crisis world. In addition, China can also expect to gain more political mileage from its trade and investment deals. For example, while investors shunned the bonds of the PIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) Beijing stepped in and purchased billions of these bonds, earning itself some goodwill among the Europeans.

But Chinese activism on the trade and investment front is also motivated by economic necessity—having to diversify its exports and secure access to commodity supplies, China needs to be far more aggressive than well-entrenched Western competitors.

If China’s commercial diplomacy principally serves the country’s economic interests and any security or diplomatic benefits are added bonuses, few would find this strategy controversial. After all, practically every country does it, and the world also prefers a China that’s focused more on commercial expansion than geopolitical domination.

Unfortunately, this isn’t entirely the case. A closer look at Beijing’s overall foreign policy suggests that Chinese leaders have often put the cart before the horse: instead of addressing the underlying causes of strategic distrust and antagonism between China and the other major powers, China excessively, if not naively, counts on economic interests to underpin its ties with these powers. Beijing appears to have bought into Lenin’s famous line: The Capitalists will sell us the rope with which we will hang them.

The reality of geopolitics is, of course, far different. Nations may be greedy, but the most powerful motivating factor in international relations is fear, particularly the kind inspired by the uncertainty over a rising power. The history of China’s own relationship with its neighbours, the United States and Europe is a useful illustration of this point. Few would dispute that China’s political ties with Japan, the US and Europe were perhaps most friendly in the 1980s, a decade in which the West’s commercial interests in China were a fraction of what they are today. But even though China was relatively poor, it was viewed as a key anti-Soviet ally. More importantly, China was politically moving in the right direction, with significant improvements in civil liberties and brighter prospects for democratic reforms.

All this changed after 1989. The Tiananmen Square crackdown in June dashed the West’s hopes for a liberal China. Then came the Soviet collapse, which also ended China’s role as a Western ally. What has helped smooth tensions between China and the West in the last two decades has been a combination of luck and Chinese prudence.

In the 1990s, the West opted for a strategy of engagement and integration with China, believing that such a course is preferable to another Cold War and was more likely to make China’s rise a peaceful one. Beijing itself also exercised strategic prudence and faithfully followed Deng Xiaoping’s dictum of ‘hiding your brightness.’ In the last decade, meanwhile, America’s strategic blunders (principally the invasion of Iraq) and the war on terror gave China another golden opportunity to build up its strength. Of course, the enormous growth of the Chinese economy since 1989 has made China a lucrative market. But overall, China’s diplomatic fortune in the last two decades has depended not on bucks, but on luck and caution.

So it’s strange that as China’s economic clout rises—and its leaders have grown more enamoured of using commerce as a tool of diplomacy—Beijing has become, strategically at least, less prudent. Instead of showing restraint on issues ranging from climate change, territorial disputes, trade and human rights, China has opted for assertiveness and confrontation. As a result, fear of China has driven Chinese neighbours—notably India, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam and Indonesia—into the ready arms of the United States. Economically, China and these countries have never been closer. Strategically, they’ve never been farther apart.

To recover from its recent diplomatic setbacks, China needs to change course. It must return to the basics of diplomacy: exercising strategic restraint to reassure its neighbours and the international community. Commerce still has a place in Chinese foreign policy, but it shouldn’t be a substitute for old-fashioned diplomacy.

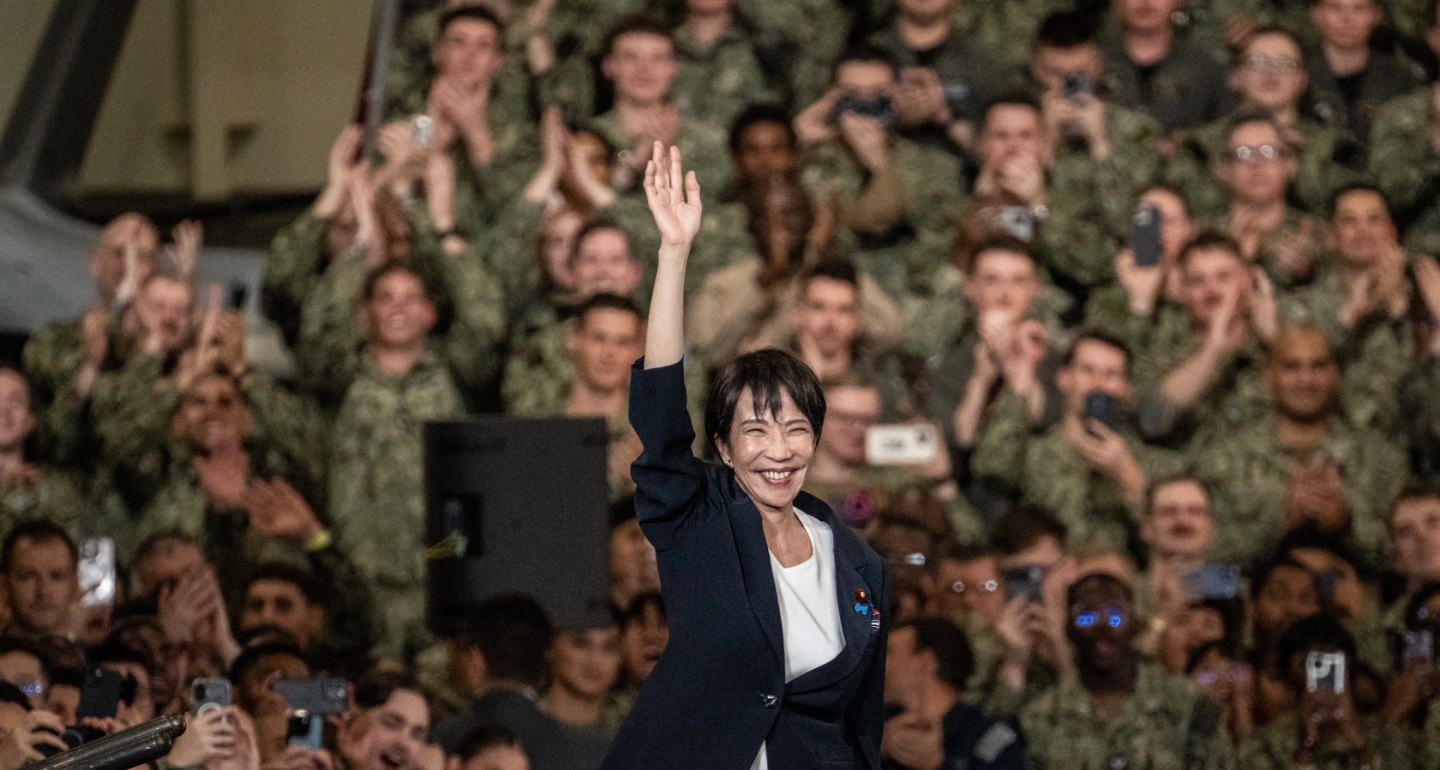

About the Author

Former Adjunct Senior Associate, Asia Program

Pei is Tom and Margot Pritzker ‘72 Professor of Government and the director of the Keck Center for International and Strategic Studies at Claremont McKenna College.

- How China Can Avoid the Next ConflictIn The Media

- Small ChangeIn The Media

Minxin Pei

Recent Work

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- China Is Worried About AI Companions. Here’s What It’s Doing About Them.Article

A new draft regulation on “anthropomorphic AI” could impose significant new compliance burdens on the makers of AI companions and chatbots.

Scott Singer, Matt Sheehan

- Taking the Pulse: Can the EU Attract Foreign Investment and Reduce Dependencies?Commentary

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Japan’s “Militarist Turn” and What It Means for RussiaCommentary

For a real example of political forces engaged in the militarization of society, the Russian leadership might consider looking closer to home.

James D.J. Brown

- A New World Police: How Chinese Security Became a Global ExportCommentary

China has found a unique niche for itself within the global security ecosystem, eschewing military alliances to instead bolster countries’ internal stability using law enforcement. Authoritarian regimes from the Central African Republic to Uzbekistan are signing up.

Temur Umarov

- Is There Really a Threat From China and Russia in Greenland?Commentary

The supposed threats from China and Russia pose far less of a danger to both Greenland and the Arctic than the prospect of an unscrupulous takeover of the island.

Andrei Dagaev