- +18

James M. Acton, Saskia Brechenmacher, Cecily Brewer, …

{

"authors": [

"Marwan Muasher"

],

"type": "questionAnswer",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Arab Awakening"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [

"Eurasia in Transition"

],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"North Africa",

"Egypt",

"Gulf",

"Levant",

"Maghreb"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Security"

]

}

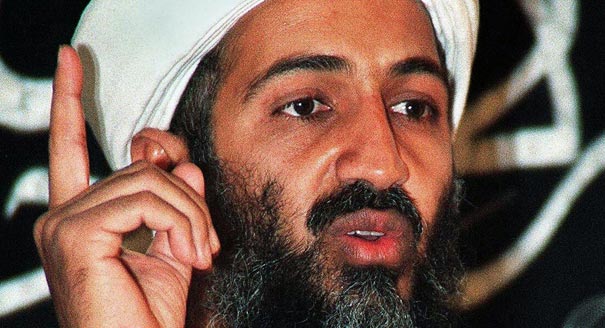

Source: Getty

Bin Laden and the Arab Spring

While the ideology of violence and terrorism has peaked and is visibly on the way down in the Middle East and North Africa, the war on al-Qaeda and terror is far from over.

The killing of the most-wanted man in global terrorism came amid a wave of upheaval sweeping across the Arab world. While it is too early to tell how Osama bin Laden’s demise will impact al-Qaeda, it is clear that it is a new Middle East.

- What is the significance of Osama bin Laden’s death?

- How has bin Laden’s sudden demise been perceived across the region?

- How have the uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa influenced al-Qaeda?

- What is the current state of extremism in the Arab world? Is extremism on the rise?

- Will the successful raid on bin Laden’s hiding spot change the perception of the United States in the region? What should the United States do next?

What is the significance of Osama bin Laden’s death?

How has bin Laden’s sudden demise been perceived across the region?

How have the uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa influenced al-Qaeda?

What is the current state of extremism in the Arab world? Is extremism on the rise?

Will the successful raid on bin Laden’s hiding spot change the perception of the United States in the region? What should the United States do next?

About the Author

Vice President for Studies

Marwan Muasher is vice president for studies at Carnegie, where he oversees research in Washington and Beirut on the Middle East. Muasher served as foreign minister (2002–2004) and deputy prime minister (2004–2005) of Jordan, and his career has spanned the areas of diplomacy, development, civil society, and communications.

- Unpacking Trump’s National Security StrategyOther

- The Widespread Fallout of Israel’s Qatar StrikesQ&A

- +1

Amr Hamzawy, Andrew Leber, Marwan Muasher, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Iran Is Pushing Its Neighbors Toward the United StatesCommentary

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

- Duqm at the Crossroads: Oman’s Strategic Port and Its Role in Vision 2040Commentary

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

- Europe on Iran: Gone with the WindCommentary

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

- What We Know About Drone Use in the Iran WarCommentary

Two experts discuss how drone technology is shaping yet another conflict and what the United States can learn from Ukraine.

Steve Feldstein, Dara Massicot