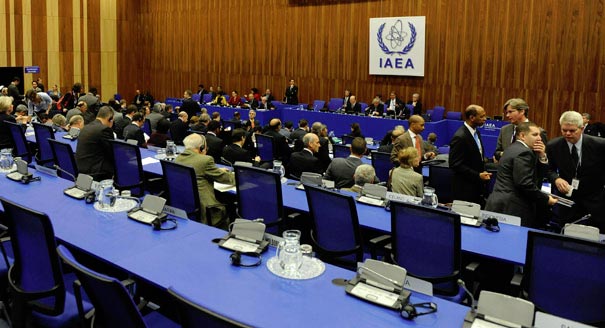

his month the two decision-making bodies of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA)—the Board of Governors and the General Conference—will convene back-to-back meetings in Vienna. On the agenda will be a range of pressing issues, including the Middle East, Iran, North Korea, and the aftermath of the nuclear accident in Fukushima.

In a Q&A, Mark Hibbs explains that the deliberations will underscore the weakness of the IAEA’s leadership compared to its 151 member states. They—and not Director General Yukiya Amano—will call the shots on all important agenda items.

What is the difference between the Board of Governors meeting and the General Conference?

The Board of Governors is the IAEA’s most important policy organ and meets quarterly to decide on the IAEA’s budget and its program of work. The board’s responsibilities include reviewing and responding to IAEA safeguards findings. This is especially important for cases—like Iran, North Korea, and Syria—where the board has requested an IAEA investigation over concerns that not all nuclear activities are disclosed. In two recent cases—Iran in 2006 and Syria this June—the board ruled they were out of compliance with their legal safeguards obligations, and, as called for by IAEA guidelines, referred those findings to the United Nations Security Council.

The General Conference convenes annually and, while the

IAEA calls the gathering its “highest policymaking body,” it has over time been eclipsed by the board. The General Conference does have weight because it is the collective voice of the 151 member states and has to sign off on key board decisions—including its purse strings. The General Conference is a valuable opportunity for all member states to exchange information, but a lot of time is spent on detailed negotiations about agenda items that have little real-world impact.

What’s on the agenda for this year’s meetings?

A main focus for both meetings will be developments in the Middle East. That’s where member states see the greatest danger that nuclear weapons will proliferate. There will be deliberations on Syria, Iran, and Israel, and efforts by the IAEA to support the establishment of a nuclear weapons-free zone in the region.

These items will likely underscore a growing narrative at the IAEA—the relative weakness of Director General Yukiya Amano compared to the strength of the major powers plus a group of politicized developing countries on the board and in the General Conference. A handful of member states will likely call the shots on all important agenda items.

Will the Board of Governors take action against Iran and Syria at the meetings?

In June, the IAEA board referred Syria to the UN Security Council for non-compliance after Syria refused for three years to allow an IAEA inspection of an installation the IAEA believes was a secret reactor that was destroyed by Israel in 2006. Amano will likely tell the board at this meeting that Syria’s lack of cooperation has continued but that he has no further developments to report.

There is media speculation that the board will take similar action on Iran. Some board members supporting the Syria resolution viewed it as

a dry run for similar resolutions on North Korea and then on Iran later this year.

As with Syria, Iran has refused for three years to discuss with the IAEA allegations that Iran’s nuclear program has a possible military dimension. In advance of the upcoming board meeting, Amano told the board on September 2 that the IAEA is “increasingly concerned” about this because it continues to collect data showing that Iran has carried out research and development for a nuclear weapon. Some information compiled by member states indicates that Iran may have paid North Korea for considerable and wide-ranging assistance. Amano’s report to the board was an attempt to magnify concerns about this matter.

While a resolution on Iran may be on the horizon, negotiations continue and therefore it’s unlikely we’ll see a decision from the board at this meeting.

In July, Iran’s foreign minister, Ali Akbar Salehi, met with Amano and told him that he wanted to improve Iran’s cooperation with the IAEA, provided that the IAEA drop the issue of weapons-related allegations from the scope of the “work plan” that the IAEA and Iran agreed to in 2007 to resolve remaining issues about Iran’s nuclear program.

The IAEA won’t agree to this. Nonetheless, the IAEA will not dismiss out of hand the possibility that Salehi is serious about finding a “carrot” to appease hardliners in Tehran to allow Iran to resolve outstanding issues with the IAEA, particularly if that would eventually lead Iran to ratify and implement the Additional Protocol. So far, however, the IAEA has no idea what that “carrot” would be. And during other encounters with the IAEA, the head of Iran’s nuclear program, Fereydoun Abbasi Davani, has spelled out that the Additional Protocol is off the table.

The P-5, the five permanent members of the UN Security Council, on the Board of Governors do not want Amano to inject himself into the search for a negotiated solution with Iran, and Amano will comply. His predecessor, Mohammed ElBaradei, did get involved in 2003, supporting a European Union-brokered deal not to cite Iran for non-compliance in return for greater Iranian cooperation. After three years, however, Iran returned to a hard line with the IAEA. Russia has now offered to negotiate a fresh diplomatic solution but this is viewed with skepticism by Western powers on the board and it isn’t clear whether Iran will agree to Russia’s offer for talks.

In theory, a Russian plan to defuse the crisis with Iran might be acceptable to China and to Western states of the P-5. Russian and IAEA discussions with Iran on how to improve cooperation would defer any board resolution on Iran at least until the next board meeting in November.

At this month’s conclaves, the board and the General Conference will also deliberate over compliance issues in North Korea. In June, some board members favored passing a non-compliance resolution on North Korea before moving on to Iran.

Can Amano intensify pressure on Iran if the Board of Governors does not take action?

Yes. In advance of the next board meeting or in early 2012, the IAEA could prepare and submit a new report to the board that could serve as the basis for a new non-compliance resolution. Amano’s role is key in this.

Until now, the Board of Governors has made findings of non-compliance six times with states’ safeguards obligations. But the head of the IAEA has a critical guiding role. In 2003, ElBaradei actively discouraged the board from finding Iran non-compliant. In June, in a step expressly encouraged and welcomed by the United States and other Western countries on the board, Amano provided the grounds for a non-compliance citing against Syria in a report to the board, assessing that it was “very likely” that Syria had constructed an undeclared reactor.

The board’s subsequent non-compliance finding explicitly referred to Amano’s report. Were Amano to now assess the credibility of evidence pointing to a military dimension in Iran’s nuclear program, Amano’s report could likewise lead to a renewed non-compliance finding by IAEA governors.

The board found Iran out of compliance in 2006, which led to Security Council sanctions against Iran. It isn’t certain that a new non-compliance finding will result in additional sanctions, but the board may nonetheless push for a new resolution to keep Iran’s nuclear program in the international spotlight.

Last year the General Conference spent a lot of time handling a resolution introduced by Arab states on Israel’s nuclear capabilities. Will we see that again this year?

Last year the United States led a push by Western states to defeat a resolution from Arab states urging Israel to join the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and give up its nuclear weapons. The United States argued that the resolution was counterproductive and that, if it passed, Israel would not attend an international conference set for 2012 to discuss the creation of a nuclear weapons-free zone in the Middle East, as was called for by all parties to the NPT in May 2010. Whether a resolution is introduced and passed, however, will have little impact on whether Israel attends the international conference.

NPT parties collectively urged the IAEA to support the 2012 conference and last year’s General Conference requested that Amano report on the matter. In light of this, Amano will inform the General Conference that he plans to hold a discussion “forum” at the IAEA on November 21-22 looking at lessons learned in other regions that established nuclear weapons-free zones. Israel has notified Amano that it will attend the meeting, provided it is “solely an informational and discussion event and not a forum for negotiations.” Amano’s role in making a nuclear weapons-free zone in the Middle East happen will be negligible, as it will be up to member states alone to negotiate such an agreement.

This year, Arab states have put the same item on the agenda. Whether their resolution passes this time again depends on whether a number of small developing countries will be firmly pressed by Western states not to support it.

Will the Board of Governors and the General Conference address the Fukushima accident?

Yes, and here too, Amano’s comparative weakness to his member states will be underscored.

In June, three months after the accident in Japan, Amano proposed to IAEA member states that the IAEA conduct safety reviews of 10 percent of the world’s 440 operating reactors over a three-year period. The reviewed reactors would be randomly selected by the IAEA. Amano argued that carrying out such peer reviews would be possible “without the need to formally amend existing legal instruments simply by member states giving their prior consent to peer review all of their nuclear power plants.”

This proposal did not find approval. Member states weakened the plan in four successive drafts negotiated between the states and the IAEA. The most recent version, which will be approved by consensus by both the Board of Governors and the General Conference, does not specify how many or when plants will be reviewed, does not permit random selection of reactors, and contains no commitment or consent by member states to any IAEA reviews. Decisions on the safety of nuclear installations will therefore remain squarely the prerogative of sovereign national governments.