Yezid Sayigh

{

"authors": [

"Yezid Sayigh"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Arab Awakening"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Egypt",

"Levant",

"Maghreb",

"Middle East",

"North Africa"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Civil Society"

]

}

Source: Getty

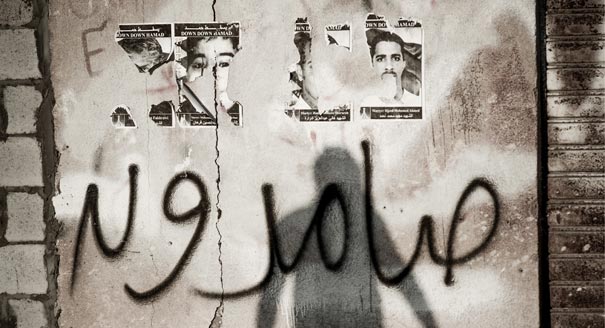

An Arab Spring Gone Sour?

It has become common to see instability and strife as the direct outcome of the Arab Spring. However, youth movements have so far performed better than most of their Islamist and supposedly secular and liberal competitors.

Source: Middle East Voices

Two years into the uprisings that rocked the Middle East, it has become common to see instability, uncertainty, and strife as the direct outcome of the Arab Spring. An Islamist threat against civil liberties appears to be strengthening. Protestors and vigilante groups commit violence amid the paralysis of police and internal security agencies. And Arab economies continue to deteriorate.

But these negative trends are in fact a legacy of the authoritarian era, in which presidents for life and the elites that emerged around them reshaped political, economic, and social life to consolidate their control. Changing a leader therefore meant disrupting the state and its institutions, if not dismantling them altogether.

The uprisings of 2011 opened major opportunities for the fundamental realignment of political actors and social forces. Any transition is inherently destabilizing, but what has made Arab democratic transition especially at risk of derailment is the extent to which the previous authoritarian era limited the ability of governing institutions and political systems to cope with change.This legacy of authoritarianism weighs heavily on Arab states today, shaping the goals and expectations of political movements, as well as forms of political organization and behavior. The forces that destroyed the old status quo still follow patterns established by their predecessors, and they have yet to realize this.

This is reflected in four main ways.

First, taking control of the state remains the central purpose of politics and its ultimate prize. The centrist Islamist parties that won a plurality of votes in Egypt and Tunisia in 2011, for instance, believe power is rightfully theirs, and they should be free to form governments, set national agendas, and promote their preferred policies in all domains. They regard the appointment of Islamist members and supporters to senior government posts as a legitimate practice that is normal in mature liberal democracies.

But these countries have not yet agreed new “rules of the game,” which they must do through compromise and consensus at this formative stage if the state and its institutions are to acquire a true democratic logic. More importantly, the intense focus on issues of representation and status have obscured the pressing need to address unemployment and poverty, generate productive investment, and pursue badly-needed administrative reforms.

Second, state power is still expected to confer economic opportunity. In Egypt and Tunisia, both the new governing coalitions and their political rivals have yet to demonstrate convincingly that they seek to dismantle crony networks and transform economic ownership and access, rather than simply take the place of previous business elites.

In Yemen, the same political actors that bargained over state patronage in the past still play a powerful role in the ongoing dialogue over reconstituting the state, with the expectation of reproducing their economic privileges and financial rewards. And in Libya, where roughly 80 percent of the population depended directly or indirectly on the oil-funded state sector for its income, the expectation once again is that the state is the principal source of employment, investment, and contracts.

Third, the authoritarian legacy casts a shadow over forms of political organization. The Muslim Brotherhood was able to translate its long history of clandestine activity into electoral victories, but is now struggling to shed the habits of operating outside the law. Its rivals are just as unfamiliar with employing peaceful methods of political contestation and in using embryonic democratic structures and procedures to compete on the basis of concrete policies, programs, and performance.

Instead, both sides have resorted to struggling over symbolic capital and identity politics, focusing in most cases on the official place of sharia, constitutions, and legislation. Where political parties have failed to gain a real foothold, such as in Libya, political actors have fallen back on other forms of social mobilization such as tribe or region. And in both Libya and Yemen, paramilitary groups have also emerged as an alternative form of political organization.

Fourth, violence remains embedded in state-society relationships and between political actors. This is manifest in the increasingly bitter struggle over the proper role of the police and internal security agencies. Some seek only to reform existing institutions with the hope of restoring basic law and order more quickly, whereas others seek revolutionary transformation of agencies with a reputation for brutality and corruption.

This is also a struggle between a militaristic culture, which advocates coercion in response to political and social problems, and one that sees policing as a public service. Yet, even those newly empowered political actors who seek to end abuses also regard the police as an instrument to promote and consolidate their own preferred social order. All too often, the police and security agencies are still seen as critically important political assets.

Reversing the authoritarian legacy will be difficult yet necessary. The contending political actors have focused their energy too exclusively on designing new constitutional systems that secure their preferences, but they must learn that democracy also requires competition over concrete policies and programs and the delivery of tangible outputs.

This is a key distinction from authoritarian modes of governance, even if it is not easily acquired. Some of the youth movements that came to prominence during the Arab uprisings display greater awareness of the need for practical solutions to concrete problems and willingness to respond through new forms of civic political organization. So too are some of the newer Salafist movements, which have responded to the democratic opening by focusing on grassroots mobilization and the promotion of social justice.

Youth, who constitute a majority of Arab populations, were not formed within the authoritarian system or in the older opposition to it. Meanwhile, salafists appeal powerfully to the 40 percent of society in countries undergoing transition that are poor or marginalized, and that also stand outside the formal political and economic system.

While new governments appear more interested in consolidating power, these “outsider” social movements may devise a counter-legacy of political pluralism conducted in the context of democratic practice. This is no guarantee of their commitment to democratization, but so far they have performed better than most of their Islamist and supposedly secular and liberal competitors.

This article was originally published in Middle East Voices.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center

Yezid Sayigh is a senior fellow at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, where he leads the program on Civil-Military Relations in Arab States (CMRAS). His work focuses on the comparative political and economic roles of Arab armed forces, the impact of war on states and societies, the politics of postconflict reconstruction and security sector transformation in Arab transitions, and authoritarian resurgence.

- What Is Israel’s Plan in Lebanon?Commentary

- All or Nothing in GazaCommentary

Yezid Sayigh

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs

- Firepower Against WillpowerCommentary

In an interview, Naysan Rafati assesses the first week that followed the U.S. and Israeli attack on Iran.

Michael Young

- Who Will Be Iran’s Next Supreme Leader?Commentary

If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

- What Is Israel’s Plan in Lebanon?Commentary

At heart, to impose unconditional surrender on Hezbollah and uproot the party among its coreligionists.

Yezid Sayigh

- Bombing Campaigns Do Not Bring About Democracy. Nor Does Regime Change Without a Plan.Commentary

Just look at Iraq in 1991.

Marwan Muasher