Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

{

"authors": [

"Karim Sadjadpour"

],

"type": "testimony",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

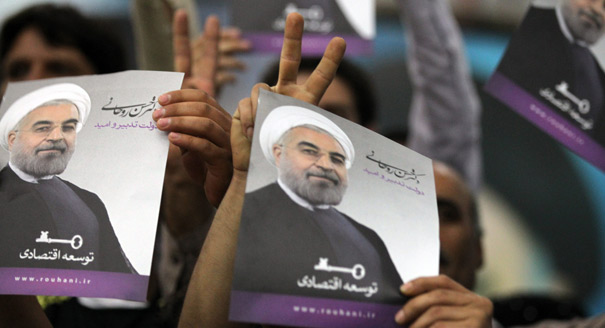

It was surprising that Rowhani was permitted to win by an unelected conservative establishment who over the last decade have systematically purged moderates and reformists from the corridors of power using force and intimidation.

Source: House Foreign Affairs Committee

The West should temper expectations for Iran’s president-elect, Hassan Rowhani, argues Karim Sadjadpour. In testimony before the House Foreign Affairs Committee, he explains why Rowhani is less a reformer than a pragmatic regime insider and outlines steps Washington can take to pursue nuclear détente and encourage a truly representative government in Tehran.

Sadjadpour concludes, “Iran is one of the few countries in the Middle East where America’s strategic interests and its commitment to democratic values align, rather than clash. . . . For less than the cost of one F-15 fighter jet, the United States can play a significant role in helping to inform the thinking of tens of millions of people in Iran who are desperate for their country to genuinely reform and emerge from international isolation.”

Testimony

Madam Chairman and distinguished members of the subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to testify before you today.

Hassan Rowhani’s unexpected June 14, 2013 victory in Iran’s presidential race was another humbling reminder that there are no experts on Iranian politics, only students of Iranian politics. What was most surprising was not that Rowhani received the highest number of votes: As the lone moderate candidate on the ballot in a nation suffocating under tremendous internal and external political and economic pressure, Rowhani’s late-hour surge was a reflection of profound discontent with the status quo rather than a deep-seated affinity for the candidate himself.

What was most surprising, however, was that the unelected conservative establishment—led by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei—allowed Rowhani to win, after a decade of systematically purging moderates and reformists from the corridors of power using force and intimidation. Paradoxically, the deliberate process of counting the 37 million ballots in 2013 made it clear to many Iranians that the ballots were not counted in President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s abruptly announced and highly contested re-election in 2009.

While the Iranian public reacted jubilantly to Rowhani’s victory—the equivalent of a light rain after eight years of drought—expectations about his will and ability to affect meaningful change in both Iran’s internal and external behavior should be tempered. Although Rowhani was endorsed by key reformist figures, including former President Mohammed Khatami, he is less a reformer than a consummate regime insider who is committed to the preservation of the Islamic Republic. Indeed, if he was anything less, he would not have been permitted to run. His campaign did not focus on pursuing democracy, or altering the Islamic Republic’s strategic principles, but on moderating its style more than its substance.

Rowhani’s victory is unlikely to alter the conditions needed for a rapprochement between the U.S. and Iran. If Washington’s goal is détente with Tehran, however, Rowhani’s victory was likely the best possible outcome of a deeply flawed and unfree electoral process.

The position of president in the Islamic Republic of Iran is neither fully authoritative nor ceremonial. The vast majority of the country’s constitutional authority rests with the Supreme Leader, who will likely continue to have effective control over Iran’s key institutions of power, including its military, media, and judiciary. Nonetheless, Iranian presidents play an important role in helping to manage the country’s economy as well as its internal political and social atmosphere.

Rowhani will have the opportunity to bring in different personnel to manage the country’s bureaucracies. In contrast to Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, who valued political loyalty and ideological fealty over competence, Rowhani will likely attempt to bring back experienced managers and technocrats to the government. During the era of reformist president Mohammad Khatami (1997-2005) the political and social atmosphere—for NGOs, newspapers, university students, and young people simply wanting to live freely—was palpably more tolerant than it has been during the eight-year tenure of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad (2005-2013).

Rowhani’s victory raises important questions about the Islamic Republic’s internal power dynamics, particularly the power of Supreme Leader Khamenei and the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC).

Rowhani’s victory has been commonly interpreted as a defeat for Khamenei. This may well prove to be true, but it is not necessarily a foregone conclusion. While voters clearly repudiated Khamenei’s policies—given the poor showing of his two closest acolytes, nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili and former foreign minister Ali Akbar Velayati—in allowing them to do so Khamenei likely helped rehabilitate, somewhat, his deeply tattered image.

The medium and long-term impact of Rowhani’s win on Khamenei’s authority is less clear. At the moment Iran’s most powerful institutions—namely the Revolutionary Guards, bassij paramilitary, Guardian Council, Assembly of Experts, parliament, judiciary, intelligence ministry, and wealthy religious foundations (bonyads), to name a few—are led by individuals who have either been handpicked by Khamenei or publicly deferential to him. To the best of my knowledge, there is not a single example of Khamenei being even mildly criticized directly by one of these institutions.

Will these forces remain deferential to Khamenei, or do they sense that the Supreme Leader’s political prowess has peaked? Will forces aligned with former presidents Hashemi Rafsanjani and Mohammed Khatami, both of whom believe the constitutional authority of the Supreme Leader must be curtailed, be emboldened by Rowhani’s win? Will Rowhani himself, similar to his three predecessors, over time begin to challenge Khamenei’s authority?

Over the last several years, there has been a prevailing narrative that the institution of the Revolutionary Guards has eclipsed the institution of the clergy in terms of their internal political and economic influence and their management of the nuclear program and sensitive foreign policy files like Syria. Despite this, it is interesting to note that Rowhani handily defeated two men—Mohammed Bagher Ghalibaf and Mohsen Rezai—who were former senior IRGC commanders. This arguably reflects concerns, from either society or Khamenei or both, about the growing role of the military in Iranian political and economic life.

Popular expectations of Rowhani are unduly high. Liberals who voted for him with the hopes that he will attempt to alter the constitution of the Islamic Republic, or aggressively champion human rights, will likely be disappointed. While Rowhani has vowed to pursue national reconciliation, it remains to be seen whether it will be a priority for him to pursue the release of 2009 opposition presidential candidates Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karoubi, both of whom have been under draconian house arrest for three years.

The Iranian president is the country’s public face to the world and plays an important role in shaping its international image. This is especially true given that Khamenei has not left Iran since 1989. Whereas reformist president Mohammed Khatami is best remembered internationally for his slogan calling for a “Dialogue of Civilizations,” Ahmadinejad will be remembered for his Holocaust revisionism and demagoguery. It is not coincidental that under Khatami Iran avoided UN Security Council censure, while under Ahmadinejad the country has been sanctioned six times by the UN.

Given that the Supreme Leader will likely retain his veto power, Rowhani should not be expected to significantly alter the deeply entrenched strategic principles of the Islamic Republic’s foreign policy, namely opposition to U.S. hegemony, the rejection of Israel’s existence, and support for “resistance” allies such as Hezbollah, Palestinian Islamic Jihad, and the Assad regime in Syria. Indeed there remain deeply entrenched forces in Iran—including, I would argue, Supreme Leader Khamenei—who see resistance against America, and the rejection of Israel’s existence, as inextricable elements of Iran’s revolutionary ideology, and among the few remaining symbolic pillars of the Islamic Republic.

In his first press conference as president-elect, Rowhani repeated Khamenei’s frequent assertion that a pre-requisite for improved U.S.-Iran relations would be a commitment from Washington to refrain from interfering in Iran’s domestic affairs. Given that Khamenei perceives the work of Persian-language media outlets, international human rights NGOs, and even Hollywood to be levers of U.S. cultural subversion—in order to foment a soft or velvet revolution—reassuring Khamenei that U.S. policy is behavior change, not regime change, may not be possible.

What’s more, while Khamenei’s opposition to the U.S. is cloaked in ideology, it is arguably driven by self-preservation. Khamenei has risen to the top, and preserved his power, in a closed environment. An opening with the United States could bring about unpredictable changes that could dilute, rather than entrench, his authority. In the words of Machiavelli, “There is nothing more difficult to take in hand, more perilous to conduct, or more uncertain in its success, than to take the lead in the introduction of a new order of things.”

Rowhani’s immediate focus is likely to be the nuclear file, an issue with which he’s intimately familiar having previously been Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator. In contrast to Saeed Jalili, the ideologically rigid current nuclear negotiator, Rowhani’s previous nuclear negotiating team—diplomats Javad Zarif, Hossein Mousavian, and Cyrus Nasseri—were all U.S.-educated, came from merchant backgrounds, and favored improved ties with Washington.

Like Rafsanjani, Rowhani belongs to a camp in Tehran—sometimes referred to as “pragmatic conservatives”—who are deeply committed to the Islamic Republic but privilege economic expediency over revolutionary ideology. “It is good to have centrifuges running,” Rowhani said in one of the presidential debates, “Provided people’s lives and livelihoods are also running.” This is in contrast to Khamenei, who has argued that compromising on the revolution’s principles could lead to the system’s unraveling, just as Perestroika, he believes, undid the Soviet Union.

Apart from philosophical differences regarding how to best sustain the Islamic Republic, Rowhani’s room for diplomatic maneuver could likely be constrained by Khamenei’s longstanding belief that compromising under pressure projects weakness and invites more pressure.

Iran continues to have sizeable influence over several key U.S. foreign policy challenges, including Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, terrorism, energy security, and, perhaps most urgently, nuclear proliferation. While on some of these issues—such as Afghanistan and terrorism, particularly mutual fears of Sunni radicalism—there are overlapping interests between the two sides, on others—namely Israel’s existence and Assad rule over Syria—Iran and the U.S. are embroiled in a fierce, zero-sum game that is unlikely to change in a Rowhani presidency.

Even in this context, however, it makes both strategic and tactical sense for the Obama administration to make a sincere attempt to commence a process of dialogue and confidence-building with Tehran. If skeptics, like myself, are incorrect, and Khamenei is genuinely interested in finding a nuclear accommodation with the P5+1—which would entail making meaningful nuclear compromises in exchange for meaningful sanctions relief—this would be beneficial for U.S. national security interests.

If, however, the Obama administration makes another concerted effort to engage Iran and is rebuffed, we will continue to expose the fact that Tehran, not Washington, is the intransigent actor. Obama’s unprecedented but unreciprocated overtures to Tehran achieved a much more diverse and robust international coalition against Iran than the Bush administration ever managed to achieve.

It is also important for Washington to think more creatively, beyond economic sanctions, about how to facilitate political change in Tehran. Iran is one of the few countries in the Middle East where America’s strategic interests and its commitment to democratic values align, rather than clash. Whereas representative governments in the Arab world, for example, have the potential to bring about political systems that are even less tolerant, and less sympathetic to U.S. interests, than the status quo, in Iran a more representative government would likely augur both greater political and social tolerance and a more cooperative working relationship with Washington.

In this context, an important priority for Washington should be to pursue policies that expedite, rather than potentially hinder, Iran’s transition to truly representative government, one in which all its citizens—including religious minorities, the non-religious, and women—can potentially be president. The best way to accomplish this goal is to inhibit the Iranian government’s ability to control news, information, and communication.

Congress can play a very important role here. Both empirical studies and anecdotal evidence suggest that the vast majority of Iranians get their news from television more than any other source. Satellite TV is by far the most important tool for Iranians seeking to access independent news coverage or information beyond the government’s censorship and control.

Unfortunately, the Voice of America’s Persian News Network (PNN) is woefully underperforming in this respect. While in just a few short years of existence BBC Persian TV has managed to become arguably the most trusted news source for Iranians—playing an indispensable role in informing people in both the 2009 and 2013 presidential elections—PNN has in contrast been plagued by mismanagement, unprofessionalism, and substandard productions.

Like the Islamic Republic, PNN’s problems will not be resolved with merely a change in a few top personnel, but will require a more fundamental overhaul. Nearly everyone who has closely monitored PNN has reached the similar conclusion that it is simply not possible to attract top-tier journalistic talent and produce modern, creative, Persian-language television within the confines of the U.S. government.

What is needed is for PNN to be taken outside the confines of Voice of America and rendered a public-private partnership, much like the BBC, which is supported by the U.S. government but managed by media professionals rather than government bureaucrats. This will not require additional funding, beyond PNN’s current budget. For less than the cost of one F-15 fighter jet, we can play a significant role in helping to inform the thinking of tens of millions of people in Iran who are desperate for their country to emerge from international isolation.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Unexpectedly, Trump’s America appears to have replaced Putin’s Russia’s as the world’s biggest disruptor.

Alexander Baunov

Baku may allow radical nationalists to publicly discuss “reunification” with Azeri Iranians, but the president and key officials prefer not to comment publicly on the protests in Iran.

Bashir Kitachaev

The story of a has-been politician apparently caught red-handed is intersecting with the larger forces at work in the Ukrainian parliament.

Konstantin Skorkin

This time, though, they’re adding even more pressure to an already beleaguered regime.

Eric Lob

The country’s leadership is increasingly uneasy about multiple challenges from the Levant to the South Caucasus.

Armenak Tokmajyan