Two weeks ago, the Premier of the State Council of China Li Keqiang visited India and Pakistan. For Li it was the first overseas trip. No doubt, this visit demonstrated that South Asia is one of the Chinese foreign policy’s key priorities. Yet it is still unclear what kind of policy China will actually pursue in South Asia. Moreover, the future Indo-Chinese relationship might not develop as smoothly as some observers predict.

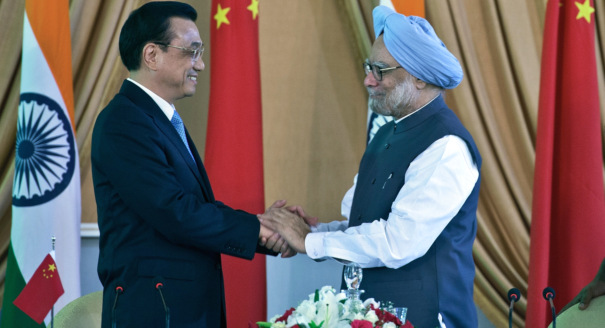

During Li’s visit to New Delhi, for example, the leaders of both countries emphasized “the comprehensive and rapid progress of India-China relations in the 21st century,” “an effective model of friendly coexistence and common development,” and “their commitment to further consolidate the strategic and cooperative partnership for peace and prosperity.”

Such was the official language of Indo-Chinese documents. Yet in unofficial discussions in Beijing and New Delhi one often hears expressions of concern about the other party’s military build-up, in particular in nuclear weapons and missile and space military technologies, mutual suspicions regarding the other side’s military activities in the border regions, and a lack of trust in bilateral relations. In Beijing there is also some concern about the U.S.-Indian rapprochement, while in New Delhi many see the ties between China and Pakistan as a threat to regional stability.

In this context it is hard to fully agree with Premier Li who said that “a successful start is halfway to final success.” In the case of the relations between China and India the success of their start must be proved by further developments. When mutual concerns and suspicions will emerge less frequently in unofficial discussions in Beijing and New Delhi, then it would be easier to believe the official statements of the leaders of China and India.

The idea of a need for a solid economic basis to a stable development of the relations between China and India appears to certainly hold true. The fact that the leaders of both countries supported this idea was reflected in almost the entire text of the joint statement being dedicated to economic issues. The ambitious plan to reach a $100 bln trade turnover by 2015 should be welcomed. But the high figures in and by themselves are not enough. The key issue is that of the quality of economic cooperation between China and India.

When you see the label “made in China” on traditional pashmina shawls in the bazaars of India, it means that the deep cooperation between China and India creates troubles in the textile industry, which used to be one of the main pillars of India’s economy. The competition with China has actually turned to be fatal for some Indian companies. If China and India follow the current model of the economic cooperation, it will surely cause the crisis of some small, medium, and even big companies of India, which will not be able to survive the competition with their “partners” from China.

The economic cooperation of good quality would provide a solid base for a stable political process between China and India. On the contrary, the unresolved economic issues between them would create more reasons for the mutual distrust, which in turn could result in a dangerous crisis.