Source: Edge

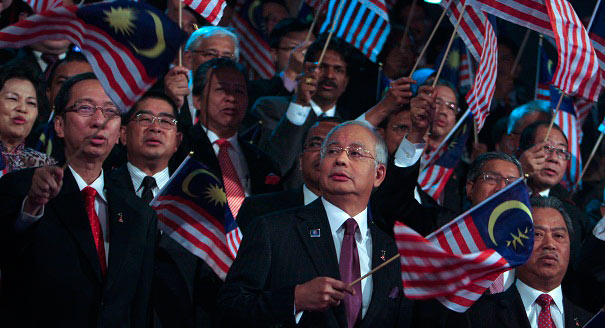

China’s President Xi Jinping is scheduled to visit Malaysia from Oct 2 to 4, about a week before the visit of US President Barack Obama. Though fortuitous, these two visits present Malaysia with a unique opportunity to foster strong relations with the world’s two most influential countries.

Malaysia-China relations have grown steadily since the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1974. Since then, every Malaysian prime minister has visited China and Chinese leaders, including Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin, Li Peng, Zhu Rongii, Hu Jintao and Wen Jiabao, have visited Malaysia. Xi’s forthcoming visit is a demonstration of the strong bilateral relations and goodwill between the two countries.

In commemoration of the 30th anniversary of establishing diplomatic ties and the steady growth in bilateral relations, former prime minister Tun Abdullah Ahmad Badawi and his Chinese counterpart agreed in 2004 to enhance cooperation in strategic areas of fundamental interest. For some time now, there has been an understanding between the Malaysian and Chinese political leaderships on the importance of elevating the bilateral relations to a higher level.

It may be opportune to formally make a joint announcement of a strategic relationship or announce the intention of such a relationship during Xi's visit. The context and purpose of that relationship should also be articulated so that the Malaysia-China strategic relationship is not misread by others. Alternatively, the joint communique can state the two countries’ desire to elevate their relations to a higher plane with details to be worked out by both sides.

The United Nations has 193 member states. Malaysia has bilateral diplomatic missions and consulates in 104 of them. Not all bilateral relationships are of equal importance. A select group of countries matter more than the vast majority for Malaysia’s national security, economic well-being and development. That select group includes major powers like the US, China, India and Japan, immediate neighbours like Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines and Myanmar as well as a few others, including the European Union, the UK, South Korea, Australia and Turkey.

There is an urgent need to prioritise these countries and develop strategic relationships with them without ignoring the others. It is in that context that I write on the importance of developing strategic relationships with the US and China, the two countries that matter most for Malaysia’s security, prosperity and well-being.

Usually contrasted with tactics, strategy is typically used in relation to warfare or more specifically, the application of force. In that context, “strategic” implies planning and manoeuvring to win a campaign as opposed to prevailing in a single battle.

“Strategic” as used in this column is a broader notion referring to the art of planning, proiecting, engaging and manoeuvring to attain broad national objectives, including in the political, economic, security and sociocultural domains. Strategic relations imply the development of bilateral or multilateral ties that are enduring over time, going beyond immediate interests and tit-for-tat reciprocity.

Designed to foster mutual support and cooperation in the pursuit of longer-term shared or exclusive national goals, strategic relationships require mutual trust, deep understanding of each other’s national, regional and global visions and goals, development to the extent possible of shared values, visions and goals, and identifying differences that are unlikely to be bridged.

Strategies, policies, frameworks, institutions and, where possible, target dates should be identified to implement shared understandings and goals, and to assist each other in the attainment of exclusive national goals. A long shadow of trust built on common values, goals and interests provides the overarching framework for strategic bilateral relations. Forging strategic relationships requires ideational and material investment as well as persistence and forbearance.

In developing strategic relationships with major powers, Malaysia faces the challenge of power and vision asymmetries. Malaysia is an emerging middle power with a national vision of becoming a fully developed country in all its dimensions by 2020 and a regional vision of peace, stability and prosperity in Southeast Asia.

The US, China, India and Japan are major powers with global and regional interests and visions. Asymmetries can be overcome in part through harmonisation, bridging and nesting of visions, goals and means. That is the task of strategy, innovative diplomacy and capable diplomats. Foreign policy and diplomacy must play a force multiplier role in forging such relationships.

Rapidly growing China is of economic and security significance to Malaysia with potential to become the world’s largest economy, China’s growing market, its rapidly increasing scientific and technological prowess and huge foreign exchange reserves are among the assets that can be tapped to support Malaysia’s economic growth and development.

Although it can be a huge economic opportunity, China could also be an economic competitor and possible threat (as, for example, in hollowing out certain sectors of the economy). In particular, Chinese methods of investment and the Chinese state's ability to strategically direct assets and opportunities require careful scrutiny to ensure economic cooperation supports not only Malaysia’s immediate concerns but also its long-term economic development goal. Cooperation with China (and other economic powers) must reflect and be integrated into Malaysia’s long-term economic development and transformation plans. The dog must wag the tail.

From a security perspective, China has become a key player in the Asian region, surpassed only by the US. Already a pole in its own right in Asia with substantial denial capabilities, China has the potential to become a global pole in due course. China figures prominently in the security calculations of all major powers, including the US.

China's security significance for Malaysia is threefold. One, China’s interactions with other major powers, especially the US, determine the context of the Southeast Asian security environment in which Malaysia has to function. Second, China’s growing prominence in global and regional governance will be consequential for Malaysia, whose national security and economic wellbeing are highly dependent on international governance. Beijing’s permanent membership in the UN Security Council, for example, can be consequential for Malaysia. Kuala Lumpur must also be mindful of Beijing’s growing significance in shaping its own regional and global roles.

Finally, China has and will continue to affect Malaysia’s national security. In the 1950s and 1960s, China supported the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) that militarily challenged the legitimacy of the incumbent government and political system. Tun Abdul Razak Hussein's foresight in establishing early diplomatic relations with Beijing (first among Asean countries) in the context of a shift in Malaysian foreign policy to a more non-aligned orientation along with the 1979 paradigmatic policy shift in Beijing helped terminate China’s support for the CPM.

At present, Malaysia has a territorial dispute with the China over the Spratly islands. The manner in which that dispute is managed and eventually settled has consequences for Malaysia’s territorial integrity. China’s claim over the entire South China Sea also affects Malaysia’s immediate security environment as well as control over important sea lines of communication in the region.

Clearly, it is important for Malaysia to develop a strategic relationship with China to manage and resolve bilateral national security conflicts, create a stable and peaceful regional security environment, tap its support for Malaysia's economic growth and foster the development of regional and global governance that supports Malaysia’s national goals (as well as Chinese goals and aspirations) and simultaneously advances the public good.

What should be the basis for that strategic relationship? History, culture, economic development, national security and international stability can be important pillars of a Malaysia-China strategic relationship. History and culture are commonly celebrated basis for the relationship. Beijing is especially appreciative of Kuala Lumpur’s early establishment of diplomatic ties with China and cultural connections between the two political entities go back for more than 1,000 years.

However, history and culture are essentially important background conditions that can cut both ways. History is context specific and subject to reinterpretation with changing circumstances. Culture can support many, and at times contradictory, behaviours. The deployment of cultural power to advance national interests must, thus, be viewed with caution.

A deeper basis for the relationship lies in the overlapping goals of economic development, national security and international stability. Malaysia’s vision of becoming a developed country in all its dimensions by 2020 is a broader goal than the Chinese Dream articulated by Xi Jinping, which on the surface appears largely domestic and economic in nature. Nevertheless, becoming a high-income economy that is globally competitive is a key component of Malaysia’s vision of becoming a developed country. That component overlaps the Chinese Dream and can provide an important basis for developing a strategic relationship over the next 10 years or more.

Though packaged attractively (a rising tide lifts all boats), the Chinese Dream may have other motives or consequences that are unclear for now. Malaysia should seriously explore the content, benefits and consequences of the Chinese Dream so that it can accentuate the benefits and mitigate negative consequences. Policymakers should explore how best to harmonise the two national visions and their economic components to realise gains for both countries while mitigating negative consequences.

Common and comprehensive national security can be another important basis for a strategic relationship. Understanding each other’s international and domestic concerns, sharing experiences and exploring innovative ways of addressing those concerns can provide an important basis for developing a strategic dialogue.

Concerns of non-interference in internal affairs may initially restrict such dialogue. However, persistence and building trust over time will help engage in a more open and fruitful dialogue. A strong bilateral relationship will also provide an important channel to discuss, amicably manage and eventually settle the troubling territorial dispute in the South China Sea as well as China’s claim over much of that sea.

International stability and governance are important common goals. Heavily dependent on the external sector for economic growth and national security, Malaysia attaches great importance to stability and governance at the regional and global levels. Likewise, China places a premium on international stability and governance.

Since 1979, the Chinese leadership has been persistent in maintaining that economic development at home requires a stable and peaceful international environment. Formulations like peaceful development and peaceful rise are reflective of the concern with international stability.

Malaysia and China should explore ways of promoting global and regional stability that is in keeping with changing circumstances with particular attention to Southeast Asia. China’s membership in, and compliance with, World Trade Organization rules and Chinese participation in regional and global governance institutions in many domains are indicative of Beijing‘s growing commitment to international governance.

That commitment, however, is tempered by the fact of a growing China still searching for its rightful place and role in regional affairs and in the world. Beijing seeks to alter the rules of the game to take account of its growing weight, values and interest. Consequently, raw power, sense of victimisation, pragmatism and narrow self-interest still dominate Beijing’s approach to international affairs, including dispute settlement.

Malaysia should support Beijing’s search for a more appropriate place and role as well as coax China (as one of the world’s two leading powers and the most powerful Asian country) to adopt a more enlightened view of regional and global governance and the provision of public goods, including the rule of law in international governance. Strategic visions, governance systems, institutions, rules and dispute settlement mechanisms are among the issues that can be discussed and developed under the heading of international stability and governance.

Armed with a strong basis, Malaysia and China should put in place processes, institutions and measures to realise a strategic relationship that benefits both countries and the region. Malaysia should develop its own road map and task relevant ministries, agencies and its ambassador to China to move expeditiously in forging a strategic relationship with China.

Some may question the possibility of developing simultaneous strategic relationships with all major powers, especially with the two leading powers whose relationship is comp1ex, comprising conflictive, competitive and cooperative elements. That is possible and indeed necessary if Malaysia is to avoid permanent alliance and alignment and ensure Southeast Asia is not dominated by any single power.

Simultaneous development of strategic relationships with multiple powers requires carefully thought out coherent national vision, goals and strategy, a deep understanding of the national visions, values, goals and strategies of relevant countries and a good grasp of the comparative advantage(s) of each relationship to maximise the benefits for Malaysia without creating enmity with others.

A clear and coherent national strategy, innovative foreign policy, effective delivery mechanisms and capable diplomats are essential to realise the goal of simultaneously developing strategic relationships with multiple powers.

This article was originally published by the Edge.