Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

{

"authors": [

"Nicholas D. Wright",

"Karim Sadjadpour"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [

"Iranian Proliferation"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "NPP",

"programs": [

"Nuclear Policy",

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Middle East",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Nuclear Policy",

"Arms Control"

]

}

Source: Getty

Wondering whether the historic nuclear talks with Iran will succeed or fail? Study the brain.

Source: Atlantic

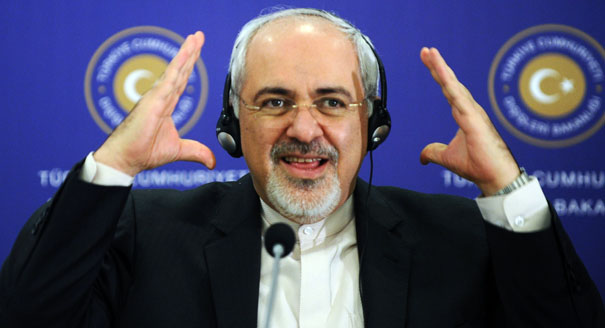

“Imagine being told that you cannot do what everyone else is doing,” appealed Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif in a somber YouTube message defending the country’s nuclear program in November. “Would you back down? Would you relent? Or would you stand your ground?”

While only 14 nations, including Iran, enrich uranium (e.g. “what everyone else is doing”), Zarif’s message raises a question at the heart of ongoing talks to implement a final nuclear settlement with Tehran: Why has the Iranian government subjected its population to the most onerous sanctions regime in contemporary history in order to do this? Indeed, it’s estimated that Iran’s antiquated nuclear program needs one year to enrich as much uranium as Europe’s top facility produces in five hours.

To many, the answer is obvious: Iran is seeking a nuclear weapons capability (which it has arguably already attained), if not nuclear weapons. Yet the numerous frameworks used to explain Iranian motivations—including geopolitics, ideology, nationalism, domestic politics, and threat perception—lead analysts to different conclusions. Does Iran want nuclear weapons to dominate the Middle East, or does it simply want the option to defend itself from hostile opponents both near and far? While there’s no single explanation for Tehran’s actions, if there is a common thread that connects these frameworks and may help illuminate Iranian thinking, it is the brain.Although neuroscience can’t be divorced from culture, history, and geography, there is no Orientalism of the brain: The fundamental biology of social motivations is the same in Tokyo, Tehran, and Tennessee. It anticipates, for instance, how the mind’s natural instinct to reject perceived unfairness can impede similarly innate desires for accommodation, and how fairness can lead to tragedy. It tells us that genuinely conciliatory gestures are more likely and natural than many believe, and how to make our own conciliatory gestures more effective.

Distilled to their essence, nations are led by and comprised of humans, and the success of social animals like humans rests on our ability to control the balance between cooperation and self-interest. The following four lessons from neuroscience may help us understand the obstacles that were surmounted to reach an interim nuclear deal with Iran, and the enormous challenges that still must be overcome in order to reach a comprehensive agreement.

More than three decades of lab experiments show that humans are prepared to reject unfairness even at substantial cost. This is based in our biology: A decade of studies using brain imaging shows that human neural activity, particularly in the insula cortex region, reflects the precise degree of unfairness in social interactions.In a classic example known as the ultimatum game, one individual gets an amount of money (e.g. $10) and proposes a split with a second player (e.g. $9 for herself, $1 for the second person). The other individual then decides whether to accept the offer (in which case both get the split as proposed) or reject the offer (in which case both players get nothing). Despite receiving an offer of free money, the second player rejects offers involving less than 25 percent of the money around half the time. In essence, unfairness has a negative value that outweighs the positive value of the money they would otherwise receive.

Even non-human primates show evidence of hardwiring to reject unfairness. In one famous study, two capuchin monkeys were instructed to carry out the same task, but one was repeatedly rewarded with sweet red grapes while the other received cucumbers. In response to such blatant unfairness, the cucumber-fed monkey threw a conniption fit.

The motivation to reject unfairness, and the humiliation that results from it, can become deeply embedded in national narratives and decision-making. In 1951, Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh rejected years of inequitable profit-sharing agreements with the British-run Anglo Iranian Oil Company by nationalizing Iran’s oil industry, even at the cost of British reprisals. Britain imposed an embargo on the purchase of Iranian oil, bankrupting Tehran’s coffers and culminating in the infamous 1953 CIA/MI6-led coup against Mossadegh, who spent the remainder of his life under house arrest.

Six decades later, this impulse to reject perceived unfairness has seemingly motivated Iran’s nuclear ambitions far more than an actual need for an indigenous nuclear energy program. In just the last few years, Iran has suffered well over $100 billion in lost foreign investment and oil revenue to defend a nuclear program that can only meet 2 percent of the country’s energy needs. In other words, Iran has debilitated its chief sources of income—oil and gas revenue—in order to pursue a project with little comparable payoff. Prominent nuclear physicists such as Princeton’s Frank von Hippel estimate that it would cost Iran at least 10 times less to import enriched uranium from abroad, as most nations that use nuclear energy now do (including, increasingly, the United States).

In an interview with NBC News’ Bob Windrem, former Iranian nuclear negotiator Hossein Mousavian conceded that the global opprobrium Iran has endured for its nuclear program defies economic logic. “If you are talking about nuclear, I will tell you no, [the pressure] isn’t worth it, definitely,” he said. “But the nuclear issue today for Iranians is not nuclear—it's defending their integrity, independent identity against the pressure of the rest.”

Why, Tehran asks, should the six global powers—five of whom collectively possess several thousand nuclear weapons—dictate terms to Iran? Why are countries like India and Pakistan—non-signatories to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) that clandestinely acquired nuclear weapons—accepted members of the international community, while Iran (an NPT signatory) is considered an international pariah? Who is Israel, a country believed to possess more than 100 nuclear weapons, to cry wolf about Iran’s nuclear ambitions?

We may not agree with these Iranian sentiments, but neuroscience tells us that rejecting perceived unfairness, even at substantial cost, is a powerful motivation unto itself.

Neuroscience also affirms that perceptions of fairness are highly subjective. We can illustrate this using the ultimatum game described above, where one individual gets an endowment (e.g. $10) and proposes an offer (e.g. a $7 to $3 split) that the other individual accepts or rejects.

One study, for example, manipulated individuals’ subjective judgment of what constituted a fair enough offer by making participants first take a short quiz to “earn” the endowment. After receiving the money in this way, they went on to make more low offers than usual in the ultimatum game. The subjects may have felt these lower offers were only fair, since they had worked to earn the cash, but this view wasn’t shared by the second party, who as normal rejected the low offers, leaving both sides with nothing.

Mutually incompatible judgments of fairness, in other words, made both players worse off. And brain imaging shows that the subjective experience of fairness, which can lead to such mutually incompatible judgments, is encoded in individuals’ brain activity.

Why does the inherent subjectivity of fairness matter? It speaks to the kind of tragedy the German philosopher Georg Hegel identified in the epic tales of ancient Greece—one arising because each side in a conflict firmly believes its position to be just.

Today, both the U.S.-Iran and the Israel-Iran conflicts can be understood in a Hegelian context. For officials in Tehran, the list of American injustices is numerous: aiding and abetting Saddam Hussein during the Iran-Iraq war (despite knowledge of Saddam’s use of chemical weapons), shooting down an Iranian civilian airplane in an incident that left nearly 300 dead, and plotting to overthrow the Islamic Republic.

To some officials in Washington, Iranians are congenital liars who took Americans hostage in 1979 and committed heinous acts of terror against U.S. forces in Lebanon and Iraq. A former U.S. general in the Middle East best reflected this disposition when he was recently asked in a private forum whether he would have been willing to meet with Iranian Revolutionary Guard Commander Qassem Suleimani: “Absolutely not … he’s a goddamn terrorist!” the general exclaimed. Such views color what both sides feel is fair treatment of the other.

While U.S. and Iranian officials have recently managed to overcome this acrimony, the enmity between Tehran and Tel Aviv will be much more difficult to transcend. Since Iran’s 1979 revolution, the rejection of Israel’s existence has been among the foremost ideological pillars of the Islamic Republic. Tehran has spent billions of dollars supporting militant groups like Hezbollah and Islamic Jihad. Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was famous for questioning the Holocaust, and Iranian Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei refers to Israel as an “illegitimate regime led by untouchable rabid dogs.”

To Israel, Iran is a fanatic theocracy whose stated goal is annihilation of the Jewish state. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has at various points compared the Iranian regime to Nazi Germany and a wild cult led by genocidal fanatics. Those close to Netanyahu say he sees himself as the protector of the Jewish people; as such, it’s natural for Israel to want to prevent a country that denies its existence from having the capability to build a nuclear weapon.

Notably, both countries see themselves as the underdog. In a military context, Iran points to Israel’s vast arsenal of nuclear weapons and sees itself as David against Israel’s Goliath. In a geographic context, Israel sees itself as David against Iran’s Goliath; Israel, after all, is 80 times smaller in size than Iran.

When both sides in a conflict feel they have a monopoly of fairness, compromise proves even more elusive.

While fairness may drive discord, it’s not necessarily our nature to punish unfairness and continue in perpetual conflict until the other side capitulates. Instead, experiments show that humans aren’t purely competitive or self-interested, but rather are also driven to cooperate.

The neural mechanisms that initiate and sustain cooperation appear in many brain-imaging studies, and involve the anterior insula cortex, a brain region that processes emotion and social norms. In one “trust game,” the first player is given an amount of money (e.g. $20) each round and can invest any portion of it (e.g. $10) with the second player. Then the investment triples, and the second player decides how much of the money to repay (e.g. returning $13 and keeping $17). Cooperation, in which higher amounts are invested and then paid back, benefits both sides but carries the risk of exploitation.

When pairs play over the course of several rounds, we see how humans maintain and repair breakdowns in cooperation. When collaboration falters and investments are low, individuals often build cooperation by making unilateral conciliatory gestures in the form of high repayments—despite the risk that these generous overtures will simply be pocketed and not reciprocated. Humans use such cooperative gestures as one tool to manage the critical balance between self-interest and cooperation.

The election of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani in 2013 reflected the Iranian people’s yearning for accommodation after eight years of near-ceaseless hostility with the West. While Iranian officials during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s presidency promoted the idea that the nation was unified behind a policy of resistance, what distinguished Rouhani from his more ideological competitors during the presidential campaign was his pragmatism. “It is good to have centrifuges running,” he asserted during one presidential debate, “provided people’s lives and livelihoods are also running.”

A critical question, however, is not just whether the Iranian people or even Rouhani are prepared for conciliation, but whether Ayatollah Khamenei and Revolutionary Guard elites are amenable to a comprehensive political accommodation with the United States. Since its inception in 1979, the Islamic Republic’s revolutionary ideology has been premised on resistance against America.

As newspaper editor Hossein Shariatmadari, often thought of as Khamenei’s official stenographer, recently put it, “The identity of both sides is involved in this conflict…. It didn’t ‘just happen.’ It is structural. The problem will be solved when one side gives up its identity, only then.” Many members of Congress would agree with Shariatmadari’s perspective, and their desire to pressure Iran with additional sanctions legislation could unravel an already tenuous interim nuclear deal.

While neuroscience tells us that genuine accommodation is natural, it has been rare in contemporary U.S.-Iran relations. “I hope that everybody appreciates the historical significance of the process,” Iranian Foreign Minister Zarif recently said. “This can change the course of our relations with the West.”

The neural mechanisms behind conciliatory gestures offer clues to render them more effective: make them unexpected. Why? The more surprising a reward or punishment is, the bigger the event’s impact is on our decision-making. According to dozens of imaging experiments, the brain has sophisticated machinery to compute the crucial difference between what is expected to happen and what actually happens.

In international relations, this finding is most often considered for punishments (the psychological impact of a surprise attack has been central to strategy since Sun Tzu). But the same can be said about diplomatic overtures (think of Egyptian leader Anwar Sadat, in a peace overture to Israel, dramatically addressing the Knesset in 1977). If the U.S. and Iran remain on the path of detente, historians years from now may point to several unexpected conciliatory gestures to explain how it came about.

In 2009, the newly elected Barack Obama sent an unexpected video message to the people of Iran and “the leadership of the Islamic Republic of Iran.” He complemented this public outreach with two unprecedented private letters to Khamenei, making it clear that America was interested in a new relationship with Iran. While Iran’s leaders were not ready to reciprocate Obama’s overtures, the U.S. president impressed upon the Iranian public that America was interested in turning the page.

Four years later, the unexpected Twitter diplomacy of the newly elected Rouhani and his foreign minister, Javad Zarif, shifted the tone of America’s foreign policy debate about Iran. Suddenly we were no longer on the verge of going to war with Iran, but potentially on the verge of a diplomatic breakthrough. The unprecedented phone call between Obama and Rouhani during the U.N. General Assembly in September heightened these expectations even more, and built confidence in both countries about the promise of diplomacy.

But with greater impact comes greater risk; surprise conciliation can go horribly awry if it is not reciprocated or perceived as an admission of weakness. Iranians who advocate accommodation are often branded traitors, while Americans who do so risk comparisons to Neville Chamberlain. Neuroscience teaches us to judiciously wield the unexpected as a diplomatic tool.

To be sure, neuroscience doesn’t provide any panaceas: a comprehensive resolution to the nuclear conflict will be extremely challenging, not least because it must accommodate Israeli security concerns, Iranian ideology, and U.S. domestic politics. At its core, the Iranian nuclear conflict is about trust. The U.S. does not believe that Iran’s intentions are purely peaceful, while Iran believes the nuclear issue is simply a pretext for regime change. As the parties try to negotiate a final deal, these lessons from neuroscience can help us comprehend the nature of the enormous trust deficit between Washington and Tehran.

Understanding that accommodation is a natural human instinct is complicated by the fact that rapprochement, which Iran’s population so desperately seeks, could be more perilous to Tehran’s top leaders than continued managed conflict. Indeed the future of U.S.-Iranian relations will be shaped as much by negotiations within Tehran and Washington—between pragmatists seeking cooperation and hardliners leery of it—as those between Tehran and Washington. The success of social animals like human beings rests precisely on managing this delicate trade-off between conflict and collaboration, a task for which we possess such exquisite neural machinery.

Former Nonresident Associate, Nuclear Policy Program

Wright was a nonresident associate in the Nuclear Policy Program at the Carnegie Endowment. His research draws on his background in neuroscience to explore political decisionmaking in economics and nuclear security.

Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Karim Sadjadpour is a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he focuses on Iran and U.S. foreign policy toward the Middle East.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber

In a volatile Middle East, the Omani port of Duqm offers stability, neutrality, and opportunity. Could this hidden port become the ultimate safe harbor for global trade?

Giorgio Cafiero, Samuel Ramani

Europe’s reaction to the war in Iran has been disunited and meek, a far cry from its previously leading role in diplomacy with Tehran. To avoid being condemned to the sidelines while escalation continues, Brussels needs to stand up for international law.

Pierre Vimont

Two experts discuss how drone technology is shaping yet another conflict and what the United States can learn from Ukraine.

Steve Feldstein, Dara Massicot

Arguing that Chinese policy is hung on alliances—with imputations of obligation—misses the point.

Evan A. Feigenbaum