- +11

Frances Z. Brown, Nate Reynolds, Priyal Singh, …

{

"authors": [

"Andrew S. Weiss"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "ctw",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "russia",

"programs": [

"Russia and Eurasia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"Russia",

"Eastern Europe",

"Ukraine"

],

"topics": [

"Security",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

Source: Getty

The Dangers of Inflexibility

Fundamental disagreements over Ukraine must not jeopardize U.S.-Russian cooperation on important issues of mutual interest, such as counterterrorism and nonproliferation.

Source: Carnegie Corporation of New York

Six months into this crisis, it’s hard to escape the impression that the U.S.-Russia relationship that emerged during the post-Cold War period has completely evaporated. As my colleague Dmitri Trenin put it so memorably in March 2014, the Ukraine crisis may mark the end of the inter-Cold War period. One hopes that Trenin’s assessment will eventually prove premature, but there are far too many indications that he was on to something.

In Washington, the Obama administration routinely pushes back against suggestions that we are entering a new cold war with Moscow. Yet any quick canvass of sophisticated opinion among the legislative branch, the intelligence community, the defense establishment, and the foreign policy kommentariat suggests that Cold War redux thinking is very much in ascendance. Unfortunately, the Obama administration’s rebuttal doesn’t sound entirely convincing amid the near total collapse of trust, the loss of routine channels of communication, and the endless flow of bad news out of Ukraine. Throw in the barrage of sanctions against the Russian economy and top figures around Russian President Vladimir Putin, and there is no basis to expect the relationship to improve until President Obama leaves office or the Ukraine crisis, in one fashion or another, is resolved. In the meantime, matters may very well get much worse.Most of the top-tier issues that used to provide structure and ballast to the bilateral relationship now lie dormant. Dialogue on arms control and strategic stability is on permanent hiatus. President Obama’s hopes to reach a historic agreement on lower numbers of strategic forces before he left office have been quietly buried. Even day-to-day business/commercial cooperation and investment ties are disrupted. That’s understandable, given Russia’s current economic doldrums, sweeping U.S./EU-led moves to choke off access to Western capital markets for Russia’s top state-owned banks and new restrictions on Russian exports of so-called dual-use and advanced oil/gas exploration technology.

If most forms of what used to be known as “business as usual” can now be seen as a reward for the disagreeable man who sits in the Kremlin, it is only natural to expect that there will be far less of it. No one knows how deep the damage will go. Ideally, cooperation on issues like counterterrorism, nonproliferation, and law enforcement will not end up being part of the collateral damage. Unfortunately, we may be entering murky terrain where a quiet tipoff about opaque threats like the Tsarnaev brothers end up becoming even more problematic for both sides’ bureaucracy.

What kinds of events could jolt both sides out of this kind of race to the bottom?

We can’t possibly know, of course, but the most likely possibility might be an exogenous regional issue such as a make-or-break moment for the long running negotiation over Iran’s nuclear activities, or unanticipated escalation of events in the Middle East. If that happens, it will probably be harder for the Obama administration or its successor to sustain the post-Ukraine status quo and continue to insist that Russia is merely a regional power.

The confluence of global crises this summer (Gaza, Ebola, Iraq, etc.) should remind all of us of the fragility of the existing global system and reignite a debate on why the post-1989 bipartisan American foreign policy vision sought to convert as many states as possible into stakeholders.

Even as we sharply disagree with Moscow’s dismaying, unacceptable behavior in Ukraine, our strategy needs to be flexible and adaptable enough to advance or protect those interests where Russia’s weight is still likely to be felt, for good or ill.

This article is part of Carnegie Corporation of New York’s Carnegie Forum: Rebuilding U.S.-Russia Relations. Read more perspectives here.

About the Author

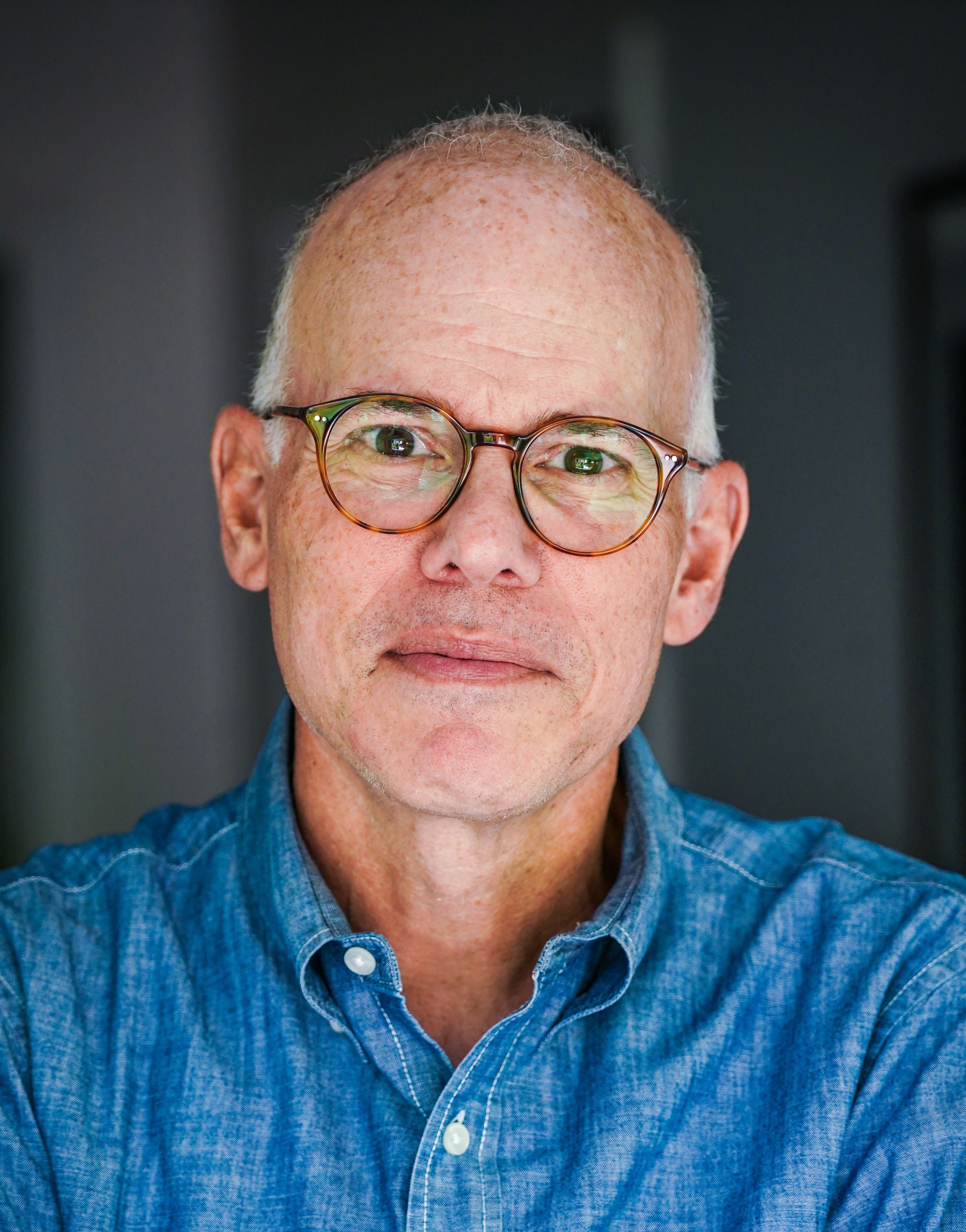

James Family Chair, Vice President for Studies

Andrew S. Weiss is the James Family Chair and vice president for studies at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he oversees research on Russia, Ukraine, and Eurasia. His graphic novel biography of Vladimir Putin, Accidental Czar: the Life and Lies of Vladimir Putin, was published by First Second/Macmillan in 2022.

- Russia in Africa: Examining Moscow’s Influence and Its LimitsResearch

- Unpacking Trump’s National Security StrategyOther

- +18

James M. Acton, Saskia Brechenmacher, Cecily Brewer, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Unintended Consequences of German DeterrenceResearch

Germany's sometimes ambiguous nuclear policy advocates nuclear weapons for deterrence purposes but at the same time adheres to non-proliferation. This dichotomy can turn into a formidable dilemma and increase proliferation pressures in Berlin once no nuclear protector is around anymore, a scenario that has become more realistic in recent years.

Ulrich Kühn

- The U.S. Risks Much, but Gains Little, with IranCommentary

In an interview, Hassan Mneimneh discusses the ongoing conflict and the myriad miscalculations characterizing it.

Michael Young

- India’s Foreign Policy in the Age of PopulismPaper

Domestic mobilization, personalized leadership, and nationalism have reshaped India’s global behavior.

Sandra Destradi

- The Greatest Dangers May Lie AheadCommentary

In an interview, Nicole Grajewski discusses the military dimension of the U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran.

Michael Young

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs