- +18

James M. Acton, Saskia Brechenmacher, Cecily Brewer, …

{

"authors": [

"Tong Zhao"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie China"

],

"collections": [

"China’s Foreign Relations"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"East Asia",

"China",

"Japan"

],

"topics": [

"Arms Control",

"Security",

"Economy",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

Source: Getty

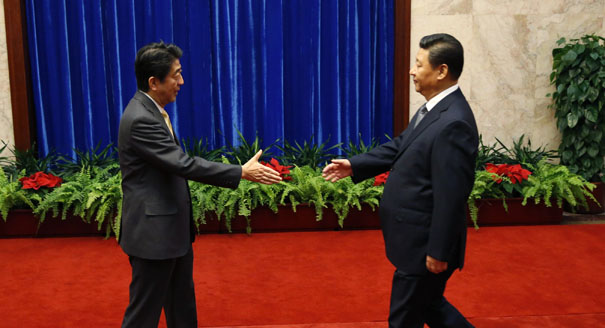

China-Japan Four Point Consensus Determines Next Important Task: Crisis Management

With the Chinese economy facing transition pressure, both China and Japan will benefit greatly from continued bilateral cooperation in the areas of economics, science and technology, and environment protection.

Source: China.org.cn

On November 7, 2014, Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi and Japanese national security adviser Shotaro Yachi met in Beijing and reached a four-point consensus regarding the Sino-Japanese relationship. The specifics of this bilateral breakthrough and official interactions between China and Japan suggest that this agreement is a result of both parties’ proactive and flexible diplomatic policy, which in turn indicates a possible direction for bilateral ties going forward.

The first thing that needs to be pointed out is this: the four-point consensus is indeed important for moving the Sino-Japanese relationship onto a positive track, but it does not mean that either side made any significant compromise regarding their positions. The agreement’s third point, which has attracted a great deal of attention, states that both sides “have acknowledged that different positions exist between them regarding the tensions which have emerged in recent years over the Diaoyu Islands and some waters in the East China Sea.” Strictly speaking, this only shows that Japan acknowledges the two sides have a difference of opinion, without saying that these disparate views regard sovereignty, and even more importantly without directly acknowledging that the Diaoyu Islands are a territory of contested sovereignty.

As to whether or not this is the first time that the two parties have officially used the name Diaoyu Islands,” each side has a different interpretation. “Diaoyu Islands” appeared in both the Chinese and English versions of the consensus released by the Chinese side, but both the Japanese and English language versions released by the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs used the term “Senkaku Islands” instead. This shows that the two countries’ positions are still not consistent with each other, although both sides have exhibited a flexible diplomatic attitude. Although neither Beijing nor Tokyo is applying pressure for other side to change its vocabulary on the islands, the two parties are continuing to use different phrasing in their own statements, and neither country has acknowledged the legitimacy of the other’s word choice.This type of flexible technical language is not uncommon in international diplomatic documents and reflects the two sides’ constructive attitude of finding common ground while respecting each other’s differences. However, this also shows that the positions taken by the two parties are not as close as optimists widely believed. In addition, there are also reports that show Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe declaring on a Japanese television show on the night of November 7 that the consensus “does not indicate that Japan’s position has changed” (regarding the Diaoyu Islands).

Based on this, it is apparent that the 4-point consensus has infused the Sino-Japanese relationship with positive energy as it continues to develop, and the agreement has also left space for further flexible adjustments. From China’s point of view, the consensus achieved an important diplomatic breakthrough and to a certain degree forced Japan to openly acknowledge the existence of different positions.

The second point of the consensus states that the two sides “have reached some agreement on overcoming political obstacles in their bilateral relations.” This may refer to a private mutual understanding that Abe will no longer visit the Yasukuni Shrine. Considering how Japan’s population has politically shifted to the right, it would be very difficult for the Japanese government to reach an official public agreement with China for Abe to stop these visits. If the two sides privately reached such an understanding, this might remove another major obstacle for high level meetings between China and Japan.

From the Japanese government’s perspective, the room for flexible interpretation that the four-point consensus furnishes will allow the administration to avoid domestic accusations that it has made major concessions to China. This should reduce the blowback from the domestic right wing camp, and will also eliminate domestic interference from either country as China and Japan further cultivate bilateral ties. Consequently, both China and Japan benefit from the four-point consensus.

But this also highlights another important variable. The Abe administration will not receive substantive acceptance from China, because the agreement has a lot of space for flexible interpretation. China will continue to “listen to its words and observe its actions,” adjusting its policy toward Japan based primarily on Tokyo’s subsequent concrete actions.

In the short term, China did not give Japan a direct commitment to hold summit meetings during the APEC Summit for this reason. Foreign Minister Wang Yi still expressed hopes on November 8 that Japan would “treat seriously, fully adhere to, and actually implement” the consensus and “create a necessary and positive atmosphere for a meeting between the leaders of the two countries.” As it stands now, in order to exhibit the generosity and attitude becoming of a host country, President Xi Jinping will probably have a brief exchange with Prime Minister Abe during the APEC summit meeting. But as to whether or not this will be a so-called “official” summit meeting, media on both sides will probably come to their own conclusions and report as they see fit.

Regardless, the summit meeting is symbolic in its own right. But what will be more worth paying attention to is how the Sino-Japanese relationship moves forward from here. For historical reasons, Japanese society’s conceptions of Japan’s war of aggression, sovereignty of the Diaoyu Islands, and the Yasukuni Shrine are different from those held by China and many other countries.

The right-leaning policies of the Abe administration have a comparatively wide-ranging base of support domestically. Under these conditions, it is very difficult for a simple exchange between the leaders of the two countries to completely reverse the differences in understanding encompassed by these issues relating to nationalism.

Another reason why the four-point consensus has positive significance is that it clearly defines the next important task for the two sides to focus upon: crisis management. Circumstances dictate that it will be difficult to make the two sides’ positions on the islands to align in the short term, and since the two sides cannot avoid continuing to defend actual control of the Diaoyu Islands, it is in both sides’ interest to explore how effective crisis management may be carried out.

Crisis management between China and Japan includes a number of goals at different levels. The first is preventing the occurrence of major accidents while the two sides are in the process of defending actual control. The second is preventing major accidents and emergencies from the situation to escalate and lead to a military conflict. The third is to the greatest extent possible isolating limited disagreements, like those involving the Diaoyu Islands and the Yasukuni Shrine, and reducing their overall impact on the relationship between the two countries, so that a long-term and all-out confrontation between the two countries may be avoided.

China and Japan have recently begun some work on the issue of crisis management and have resumed talks through the mechanism of maritime liaisons between the two militaries. After establishing a means for normalized patrols of the waters around the Diaoyu Islands, China has in recent months limited the frequency of these operations to an appropriate degree. Given that the four-point consensus especially emphasizes crisis management, it is likely that the two sides will adopt more positive measures, and it is hoped that China and Japan will resume relevant discussions as quickly as possible, talks that include topics such as establishing a hotline between high-level military officials in the two countries.

Coincidentally, the four-point consensus’s pledge to “continue to develop a mutually beneficial China-Japan strategic relationship” and to “gradually resume political, diplomatic, and security dialogue through various multilateral and bilateral channels” parallels the highest level of crisis management: preventing limited disagreements from becoming all-out confrontation. As the second and third biggest economies in the world, China and Japan have both realized that allowing limited conflicts to damage overall bilateral engagement and cooperation is unwise. Isolating limited and political conflicts from normal interactions in other areas fits with the basic interests of the people in both countries.

While high-level diplomacy was frozen, Chinese leaders still met with a large number of Japanese individuals from business and political circles to express their positive attitude that they were willing to move forward with people-to-people exchanges among the general public, business communities, educational and cultural groups, and other parts of society.

Seeing as the Chinese economy is facing transition pressure, both China and Japan will benefit greatly from continued bilateral cooperation in the areas of economics, science and technology, and environment protection. This is also an important indicator of a mature relationship between two neighbors that are both vital players in the international community. It is my hope that achieving the four-point consensus will have a substantive encouraging effect on the deepening of cooperation between the two countries in these arenas.

This article was originally published in Chinese by China.org.cn.

About the Author

Senior Fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program and Carnegie China

Tong Zhao is a senior fellow with the Nuclear Policy Program and Carnegie China, Carnegie’s East Asia-based research center on contemporary China. Formerly based in Beijing, he now conducts research in Washington on strategic security issues.

- Unpacking Trump’s National Security StrategyOther

- The U.S. Venezuela Operation Will Harden China’s Security CalculationCommentary

Tong Zhao

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Iran War Is Also Now a Semiconductor ProblemCommentary

The conflict is exposing the deep energy vulnerabilities of Korea’s chip industry.

Darcie Draudt-Véjares, Tim Sahay

- The Other Global Crisis Stemming From the Strait of Hormuz’s BlockageCommentary

Even if the Iran war stops, restarting production and transport for fertilizers and their components could take weeks—at a crucial moment for planting.

Noah Gordon, Lucy Corthell

- Taking the Pulse: Is France’s New Nuclear Doctrine Ambitious Enough?Commentary

French President Emmanuel Macron has unveiled his country’s new nuclear doctrine. Are the changes he has made enough to reassure France’s European partners in the current geopolitical context?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- The Iran War’s Dangerous Fallout for EuropeCommentary

The drone strike on the British air base in Akrotiri brings Europe’s proximity to the conflict in Iran into sharp relief. In the fog of war, old tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean risk being reignited, and regional stakeholders must avoid escalation.

Marc Pierini

- India’s Foreign Policy in the Age of PopulismPaper

Domestic mobilization, personalized leadership, and nationalism have reshaped India’s global behavior.

Sandra Destradi