Yezid Sayigh

{

"authors": [

"Yezid Sayigh"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "menaTransitions",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center",

"programAffiliation": "MEP",

"programs": [

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"Levant",

"Israel",

"Palestine",

"Middle East"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform"

]

}

Source: Getty

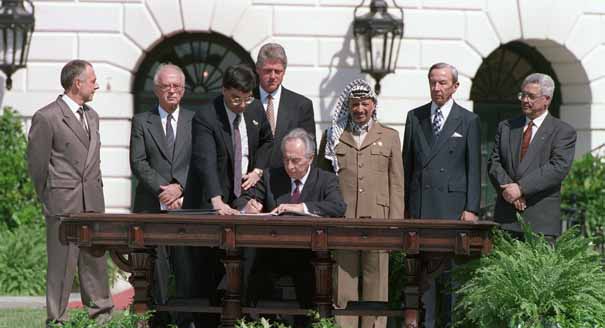

The Oslo Accords: Original Sin or Opportunity Lost?

Contention about the pros and cons of the Oslo Accords is unlikely to end anytime soon.

Source: Al Jazeera

Contention about the pros and cons of the Oslo Accords, which were signed by Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in September 1993, is unlikely to end anytime soon.

But what is incontrovertible is that they created a strategic opening for new forms of Palestinian action from which, ironically, even opponents of the accords such as Hamas ultimately benefitted.

The critical failing, from a Palestinian perspective, was that the energy invested in constructing an autonomous governing order and waging domestic political contests during the interim period was not matched by a systematic mobilisation to mount a sustained challenge to Israel's unrelenting settlement programme.Palestinian critics such as Edward Said were certainly not wrong in finding serious flaws in the Oslo accords, which allowed the Israeli government to reproduce its "matrix of control" - the interlocking systems of military administration, settlements and their connecting road networks, and bureaucratic-legal measures – in the occupied Palestinian territories.

But arguments that the accords precluded any other outcome but failure and complete national submission were based on an excessively static reading of actual and potential political dynamics.

Nor was PLO Chairman Yasser Arafat wrong in believing that political realities on the ground would evolve rapidly beyond the strict letter of the Oslo accords. But his reading of which political realities needed to be changed, and how to do so, was fundamentally flawed.

During months of talks leading up to the signing of the "implementation agreement" in Cairo in May 1994, for example, he refused to discuss its practical details with his own negotiators (let alone the Israelis). Instead, his one concern was to secure Israeli agreement for a Palestinian policeman and flag to stand at the Jericho border crossing with Jordan, symbolising the "sovereignty" he was certain would soon be realised in full.

Arafat was convinced that his Israeli counterparts understood the entire premise of the Oslo accords was to lead to Palestinian statehood, and that in signing they had already consented de facto to this outcome.

So why tussle over practical details like control of the population and land registries, responsibility for infrastructure, public works, and water resources in areas remaining under Israeli control, terms of access and movement for people and goods, or any of the other myriad arrangements governing daily life when these were only temporary and would be superseded automatically once Palestine became independent?

Why invest political capital in contesting Israel's hyper-active programme of settlement construction and expansion in the occupied Palestinian territories, since, as Arafat thought, settler pullouts and territorial compromise were going to be an inevitable part of a package deal anyway? And why invest time and energy in mobilising Palestinian society, Israeli public opinion, and the international community in the meantime, since statehood was essentially a "done deal"?

The opportunity for contestation and mobilisation was certainly there. The PLO, along with the Palestinian Authority (PA) it established in 1994, enjoyed unprecedented recognition as a legitimate political partner. Palestinian activists and spokespersons could reach every Israeli household through the media - and through face-to-face contact in meeting halls and campuses - an unprecedented advantage for a movement still pursuing national liberation.

In March 1999 the European Union officially deemed the Palestinian right to self-determination "including the option of a state" to be unqualified, neither "subject to any veto" nor contingent on reaching a negotiated solution, joining the majority of countries worldwide that had already declared unconditional support for the same principles.

These were the "golden years" of the Oslo era, during which the PLO and its various factions and political parties- including those in opposition such as Hamas - enjoyed extensive freedom to organise and recruit, launch mass media, and maintain a public presence throughout the autonomous PA areas – including the outlying neighborhoods of East Jerusalem.

They could have revived the rich experiences and impressive "people power" of the first intifada in order to challenge every new site of Israeli settlement activity and to assert the Palestinian claim to east Jerusalem through daily demonstrations and mass sit-ins.

Active, nonviolent, resistance against further colonisation of the occupied Palestinian territories, would have been seen as legitimate internationally.

Even more critically, it would have faced the Israeli electorate squarely with a choice between peace or more settlements, giving the Israeli peace camp extra leverage.

Instead, Arafat focused almost exclusively on consolidating the PA's internal political and social control, while Palestinian opponents of the Oslo Accords focused equally single-mindedly on disputing their legitimacy and brandishing their own nationalist credentials.

The result was a collective failure to confront Israeli policies that were most corrosive of the peace process.

When Israeli bulldozers broke ground to build a major new settlement at Jabal Abu-Ghneim (Har Homa) between Jerusalem and Bethlehem in 1997, for example, the only Palestinian response (beyond rote denunciations in the media) came from parliamentarians Faisal al-Husseini and Salah al-Ta'mari and a handful of activists who pitched a protest tent at the foot of the hill.

Acting differently would have required a Palestinian leadership that not only understood Israeli society and grasped the need to engage it, but which also saw Palestinian society as an equally critical actor to be methodically mobilised and cast in a central political role, rather than treated as an essentially inert resource to be activated instrumentally when needed for bargaining pressure against the Israeli government.

Consequently, the Palestinian leadership failed to assess correctly the full implications of the assassination of Rabin by an Israeli ultra-nationalist in 1995, and to redouble their effort to engage the Israeli political and security establishments and, especially, the Israeli public.

Nor did the end of the five-year interim period in 1999 prompt a new strategy combining the commitment to negotiations with the sort of state-building measures that the PA subsequently undertook - but only under radically adverse circumstances - in response to the international Quartet's 2003 Roadmap to Peace in 2003 and in its bid for statehood via the UN since 2011.

Faced with the massive imbalance of power with Israel - institutional and economic, not just military - that Said and others rightly pointed out, the Palestinian leadership should have worked to redress it by ceaselessly mobilising Palestinian society and tirelessly engaging its Israeli counterpart.

Their failure to do so helped set the stage for the militarisation of the second intifada, marginalisation of the grassroots movement, and eventual collapse of the Palestinian political system. Twenty two years later, when Arafat's successor Mahmoud Abbas told the United Nations General Assembly on September 30, 2015, that the PLO will no longer be bound by the Oslo Accords, the conditions no longer exist for the same kind of mobilisation.

But these serial failures were not preordained by the Oslo Accords.

This article was originally published by Al Jazeera English.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center

Yezid Sayigh is a senior fellow at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut, where he leads the program on Civil-Military Relations in Arab States (CMRAS). His work focuses on the comparative political and economic roles of Arab armed forces, the impact of war on states and societies, the politics of postconflict reconstruction and security sector transformation in Arab transitions, and authoritarian resurgence.

- What Is Israel’s Plan in Lebanon?Commentary

- All or Nothing in GazaCommentary

Yezid Sayigh

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Who Will Be Iran’s Next Supreme Leader?Commentary

If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

- Turkey Has Two Key Interests in the Iran ConflictCommentary

But to achieve either, it needs to retain Washington’s ear.

Alper Coşkun

- What Is Israel’s Plan in Lebanon?Commentary

At heart, to impose unconditional surrender on Hezbollah and uproot the party among its coreligionists.

Yezid Sayigh

- Bombing Campaigns Do Not Bring About Democracy. Nor Does Regime Change Without a Plan.Commentary

Just look at Iraq in 1991.

Marwan Muasher

- Iran Is Pushing Its Neighbors Toward the United StatesCommentary

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy