Russia will begin building a new strategic base for its Pacific Fleet on Matua, one of the islands of the Kuril archipelago, before the end of the year, media reported in June. It has also begun implementing a third state program for the socioeconomic development of the Kuril Islands, this one amounting to 70 billion rubles over the course of 10 years. Moscow hopes that a decade from now the Kuril Islands, which are currently mentioned primarily in the context of the territorial dispute over them with Japan, will become so attractive that local residents—like the inhabitants of the Falklands several decades ago—won’t even think of switching their territorial status.

Of the 56 islands in the Kuril archipelago, Japan, which controlled the islands from 1875 to 1945, only claims the southern islands: Kunashir, Iturup, and Shikotan, as well as the Habomai group of islets.

By 1945, Japan’s military contingent on the islands comprised more than 80,000 soldiers and officers. Within three years of the end of World War II, the Ainu residents—the original settlers of the Kuril Islands—and the Japanese were deported to Japan, leaving behind numerous military facilities.

Following the war, the Soviet Union bolstered its military presence on the islands and also resettled civilians there; by the first half of the 1960s, the population was at about 20,000. It peaked at almost 30,000 in the late 1980s, when salaries on the islands were twice as high as the national average.

However, the collapse of the USSR resulted in a severe crisis for the islands, which experienced depopulation throughout the 1990s: military divisions were withdrawn, enterprises were closed, and production of fish—the islands’ main industry—dropped by almost two-thirds compared to 1984.

During this period, when the international dispute over the islands escalated on the back of tough economic conditions in the region, residents of the Kurils felt the uncertainty of their status and the isolation from mainland Russia most acutely. In a 1993 survey of 1,098 residents of Malokurilskoye settlement (Shikotan Island), 83.4 percent were in favor of ceding the island to Japan. In 1998, 44 percent of surveyed residents of Iturup, Kunashir, and Shikotan supported returning the islands (42 percent were opposed).

By then, the population of the Kurils was down by half from the Soviet period. Many settlements were abandoned, while in others, half of the buildings were reduced to rubble. Transit between the islands and with the mainland—mainly by sea—was sporadic due to challenges in navigation.

Russia’s first program for the islands’ socioeconomic development, approved in the early 1990s for 1994–2005, was botched. Of the 150 projects envisaged, fewer than 40 were carried out. The regional GDP, which was supposed to more than double, increased only 20 percent.

For the next program, planned for 2007–2015, almost 35 billion rubles was allocated from various budget levels for the region’s development, but again, only 21 out of 38 projects were completed. There were delays in construction of new facilities, while projects that were completed were marred by violations: local authorities in Kunashir made a big show of building a kindergarten and demonstrating it to then president Dmitry Medvedev, but almost immediately after it was commissioned, cracks began to appear all over the building, rendering it unusable.

Few of the new fishing enterprises listed in the program materialized, and the housing situation was equally grim. Average per capita housing on the islands does not exceed 15 square meters, compared to the national average of 24 square meters.

Nevertheless, the Kuril Islands ultimately benefited from the federal program: new houses and even some new roads were built. A modern airport, which made regular transportation between the mainland and the islands possible, was constructed in Iturup, where two new fishing enterprises were launched. A new school and a new hospital were opened in Shikotan, and a wind farm went into operation in Kunashir.

The authorities did not succeed in raising the population of the Kurils to 30,000 as planned, but they were able to at least stem the outflow, and regional officials accordingly declared that they had fulfilled the 2007–2015 program.

Under the latest program, which covers the period through 2025, the funding allocated for the islands’ development was almost doubled to 70 billion rubles (around $1 billion at current exchange rate). Much of this increase has already been eaten up by the ruble devaluation, but the amount is still considerable for a territory with a population of under 20,000.

During the next ten years, the regional authorities plan to build 123,000 square meters of housing, eight kindergartens and schools, and eleven fishing plants. Four ports will be repaired or rebuilt, and three more ships should ensure uninterrupted passenger and cargo transit between the islands and with Sakhalin, Kamchatka, and the mainland.

In addition to the traditional fishing industry, production of rhenium—a metal used in aerospace engineering that costs more than $3,000 per kilogram—is expected to begin on Iturup this year.

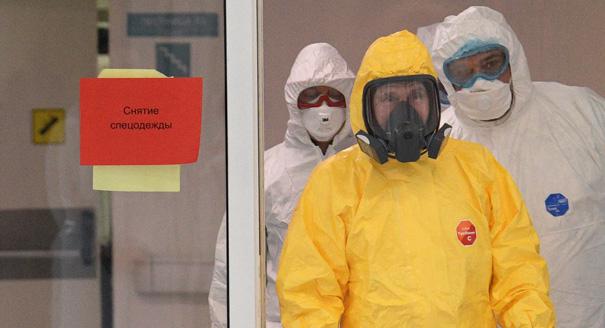

The military presence on the Kurils will also be expanded considerably: the establishment of a base on Matua is just part of the new Ministry of Defense doctrine with regard to the islands. The military announced several years ago that it would renovate the infrastructure, but back then contracts for the construction of new garrisons fell through. This time, the Federal Agency for Special Construction of the Ministry of Defense declared that it would erect 466 buildings and structures on the islands.

In addition, the Ministry of Defense will reinforce its military contingent in the Kurils. This year it will deploy the Bal and Bastion coastal missile systems, as well as new-generation Eleron-3 drones, to the islands.

Of course, even if all these many plans come to fruition, the Kurils will still be very different from the more prosperous British Falkland Islands, and the latest development program has little to set it apart from previous programs.

Yet there is one important distinction. This time, the military will be the main guarantor that at least some of the projects are implemented. Considering how adamant the government is about not cutting military expenses even despite the economic crisis, this guarantee holds weight.