Andrey Pertsev

{

"authors": [

"Andrey Pertsev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

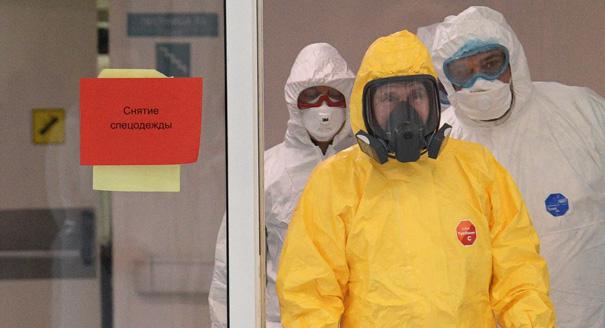

Following Orders: Putin’s New Strongmen Governors

President Putin has appointed military and security strongmen to be governors in three regions and removed an unpopular local leader in Sevastopol. He wants to tighten control ahead of the parliamentary elections.

In one morning last week, President Vladimir Putin fired four governors and four federal district presidential envoys. In three regions, the president has brought in strongmen (siloviki in Russian) to tighten the control of the Kremlin just on the eve of the parliamentary elections.

The Kremlin clearly hopes that the appointments can achieve an effect similar to the one that occurred in 1999, when Boris Yeltsin picked Vladimir Putin as his successor and turned around the public mood. The locals in these regions are apparently fed up with living with an internal political drama with multiple political actors, so outsiders are being called upon to restore order and some kind of normalcy.

These expectations can be met for at least one and a half months until the Duma elections take place in September. But the enchantment will soon wear off as locals see that the outgoing tarnished politicians are being replaced by military types with a very particular understanding of what business and politics are all about.

In Kaliningrad and Yaroslavl regions, the strongmen have been put in charge of places that have shown disobedience to the center. Both men are outsiders. Yevgeny Zinkevich is the head of the Kaliningrad regional FSB, or domestic security service, having come to the region only last year. Deputy Interior Affairs Minister Dmitry Mironov has been put in charge of Yaroslavl, despite having no ties to the region whatsoever.

Yaroslavl delivered the lowest level of support to the ruling party, United Russia, in the entire country in the 2011 Duma elections, in no small part because of its unpopular governor. In 2009–2010, thousands of Kaliningrad residents protested against its then governor. Neither of the men were locals. The Kremlin then tried to pacify the two regions by appointing locals, both of whom did a decent job. But both men also opted for policies of compromise with local rivals more than loyalty to the center. In Yaroslavl, the authorities didn’t intrude in local elections, allowing strong candidates of different political stripes to run.

In Kirov region, the Kremlin has replaced governor Nikita Belykh, who is being prosecuted in a high-profile corruption case, with another silovik with a security service background, Igor Vasilyev. Tula region, meanwhile, has also taken as governor another man closely trusted by the president, Putin’s former bodyguard Alexey Dyumin. Dyumin is running as an independent in this Duma election, enjoying the support of other political parties, including Just Russia and Liberal Democrats.

The Kremlin has also changed the head of the Crimean city of Sevastopol, but this change seems to be more in response to public demand.

In this case, the dismissed governor Sergei Menyailo is a military man and the new appointee to run the city, Dmitry Ovsyannikov, Russia’s deputy minister of industrial policy, is a civilian. Menyailo had alienated too many people in his two years on the job with his brashness and arbitrary decisions. Locals started opposing illegal construction in natural reserves, organizing rallies, and staging pickets.

Menyailo feuded with Alexey Chaly, Sevastopol’s popular “people’s mayor,” who wanted his job. Menyailo managed to win the bureaucratic war against Chaly, but lost all his public battles.

The upcoming Duma elections again proved decisive; it looked as though the governor was unable to guarantee a win for the United Russia candidate in the city. The Kremlin could not allow the blow to prestige it would suffer if the ruling party lost in the “sacred city” of Sevastopol. That would suggest that the locals had failed to appreciate the Russian government’s efforts to unite Crimea with Russia.

After two years of rule by Menyailo, the Kremlin chose not to tap another silovik as Sevastopol governor. The chosen appointee Dmitry Ovsyannikov has business experience and knows how to make deals. He will promise elections and federal investments. Local websites are reporting that sales of champagne have risen in response to the news.

Why the new appointments? These new governors are men the Kremlin will definitely find it easier to work with. There can be no subordinate more loyal than a former military or security official. They don’t question orders but follow them. They will deliver the number of votes United Russia needs in the elections.

Russia has had bad experiences of having strongmen as governors before, such as former generals Alexander Lebed and Vladimir Shamanov. Both still conjure up nightmares for their former subjects. They flew back to Moscow on weekends; they ordered local businessman to make way for their friends; and no one dared to question their orders.

Above all, the placing of military and security personnel into regional positions of power suggests that the Kremlin power vertical, dominated by siloviki, chiefly looks out for its interests. Of course, there is nothing new in this. Elites traditionally make appointments in their own image.

Men in uniform are neither politicians nor economists. Even Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov conceded that they have little management experience. At best, the Kremlin is offering its citizens the idea of order in a rather abstract sense. At worst (and that’s exactly how Peskov’s words can be interpreted), the authorities are telling them: you and your territories are subject to our requirement to restore order—to a military exercise, if you will.

It’s symptomatic of the state of the country that the Kremlin made these changes so openly on the eve of the Duma elections, a time when a ruling regime traditionally tries to pay at least some attention to its voters. The new appointments suggest that the governors will be required to instill discipline and order in their subjects, who are expected to be quiet and obedient.

About the Author

Andrey Pertsev

Andrey Pertsev is a journalist with Meduza website.

- The Kremlin Is Destroying Its Own System of Coerced VotingCommentary

- Why Is the Kremlin Punishing Pro-War Russian Bloggers?Commentary

Andrey Pertsev

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya