Andrey Pertsev

{

"authors": [

"Andrey Pertsev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

Against Everything: Russia’s New Majority

There is a new political majority in Russia. It doesn’t believe in the country’s rulers, its opposition, or its institutions. This nameless, voiceless majority is characterized only by general discontent; it knows only what it stands against.

At first, it looked like Russia’s parliamentary elections had gone extremely well for Vladimir Putin’s United Russia party: it won a constitutional majority in the State Duma, which gave the party—and therefore the president—free reign to implement social reforms such as raising the retirement age, or to pass legislation aimed at quashing dissent. The other statist parties that won seats in parliament—the Communist Party (CPRF), the Liberal Democratic Party (LDPR), and Just Russia—did so with the blessing of the Kremlin, and can be expected to remain loyal to the president.

What’s more, the opposition came out of the elections completely demoralized. Together, the liberal Yabloko and PARNAS parties received less than 5 percent of the vote, and nothing indicates that they are going to do anything about the rampant election fraud that has been reported.

But in spite of all this, many in the Kremlin are concerned about the results of the elections, which showed above all how out of touch the Russian state is with the Russian people.

The September 18 elections saw the lowest turnout in the history of Russian parliamentary elections—48 percent. This is psychologically significant: more than half of the population ignored the elections. Taking turnout into consideration, only a quarter of Russians voted for United Russia, which essentially bills itself as the “Party of the President.” Twenty-five percent support for a national leader is worryingly low.

Putin explained this away by commenting on the fact that people voted for United Russia despite the difficulties the country is currently experiencing. He argued that traditionally, low turnout is a sign that people are happy—they don’t want to change anything so they don’t come out and vote.

In reality, the opposite is true. The people didn’t rally around their leader; the majority of Russians who didn’t go to the polls showed that they are equally indifferent to the country’s rulers and its opposition.

It’s difficult to paint a picture of this new majority, but it is possible to trace its contours. When we take a look at regions where there has historically been less fraud, we can see that United Russia’s support grew compared to the last Duma elections, roughly proportionally with the decrease in turnout. The ruling party’s constituents showed up to vote, while supporters of other parties—CPRF, Just Russia, and even Yabloko—stayed home.

For the Kremlin, it would have been better if the Communists had won 15 or 20 percent of the vote—that way, it would have been clear with whom the Kremlin needed to negotiate and whom it needed to appease. Now, however, there just isn’t anyone for the authorities to work with. For the Kremlin—and the president, who thought he understood what the Russian people wanted—this a big problem.

This anonymous majority has no face and no representatives. It can only be described apophatically: they are not communists, not supporters of PARNAS, not ultra-patriots, and not Alexei Navalny cheerleaders.

Growing support for the LDPR (in the Duma elections, Vladimir Zhirinovsky’s party scored almost as many votes as the Communists) offers some insight into this majority. The LDPR’s electorate consists roughly of two types of voters: fans of Zhirinovsky’s theatrical style, and those who consider him and his party to be a real part of the opposition (there is considerable overlap between these two groups). Now, however, the party is broadening its reach, winning over voters in progressive regions such as Novosibirsk and Sverdlovsk in the Duma elections.

These people are the part of the new majority that decided to vote. This majority, like the LDPR, can’t really say what it stands for, but it knows what it’s against—pretty much everything. It doesn’t believe in Russia’s rulers, its opposition, or its electoral institutions. This nameless, voiceless majority is characterized only by general discontent. Its voters don’t care for the nuances of party politics; they recognize four familiar letters, remember Zhirinovsky’s colorful personality, and vote.

From the regime’s perspective, these contrarian voters made an OK choice. But their demands have not been satisfied; they checked a box, but their anger hasn’t disappeared. The future of this non-Putin majority is unclear, though it certainly won’t become a political force overnight. Still, this group has done something important: it showed its discontent by refusing to vote or by refusing to vote for Putin.

“You don’t even represent us!” the participants of the Bolotnaya Square protests told the Kremlin in 2011. They knew who could—or should—represent them in parliament. Russia’s new discontents, however, have no representation—for now.

About the Author

Andrey Pertsev

Andrey Pertsev is a journalist with Meduza website.

- The Kremlin Is Destroying Its Own System of Coerced VotingCommentary

- Why Is the Kremlin Punishing Pro-War Russian Bloggers?Commentary

Andrey Pertsev

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

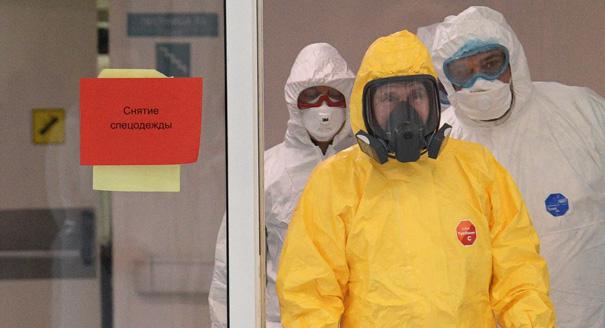

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya