Russian authorities almost always use terrorism as a justification for new restrictions on civil liberties or other forms of repression. The so-called “Yarovaya laws,” fines for reposting material on social media, the security services’ outsize role in everyday life, and even the Kremlin’s intervention in Syria—all these were portrayed as necessary to ensure security. The message from the Kremlin is clear: “Do you want to be like Europe, where tolerance and freedom do little to protect people from terrorist attacks?”

Under Vladimir Putin, the Kremlin’s fight against terror has been a cornerstone of state policy, the basis for a social contract with the Russian people. When Putin won election for the first time in 2000, it was in part because of his image as a strongman, as someone who could restore order and suppress the violence in the North Caucasus. This struggle continued through the beginning of the 2000s, after which, the myth goes, Russia became free from terror.

Though attacks happened—in the Moscow metro in 2010 and in Volgograd in 2013–2014, for example—they were portrayed as distinct events rather than as a symptom of any broader domestic chaos. After terrorists pledging allegiance to ISIS began launching attacks in Europe, this sense of security only increased, as officials and state propaganda outlets made clear their belief that European authorities bear some of the blame for the tragedies that have befallen their countries.

In this sense, terror in Russia is described in relative terms; the Kremlin repeatedly emphasizes that the kinds of attacks perpetrated in London, Nice, Paris, and Brussels would be unthinkable in Russia.

The fight against terrorism has always been offered as a justification for repressive initiatives. The 2004 gubernatorial elections were canceled after the Beslan hostage crisis, and in 2015, when Moscow began its campaign in Syria in part to keep ISIS from carrying out attacks in Russia, could anyone question additional budget expenditures? These are the costs, the Kremlin says, of living in peace.

Broadly, the North Caucasus notwithstanding, there is a consensus among the Russian population that the government’s hardline stance on terror has prevented attacks from being perpetrated. This guarantee of security has allowed authorities to ignore a host of social and economic problems. But there is a significant downside to this model: any attack on Russian soil begins to erode the underpinnings of the Kremlin’s social contract.

This is a losing strategy precisely because it is such a well-worn one. Whereas in 2000 it was the basis for a new national project, this strategy now raises more questions than it answers: What did seventeen years of security concerns get us? For years, authorities have told us that attacks happen in Europe because authorities there are weak and do not know how to govern. Now that terrorism has come to Russia again, does this mean our authorities are weak, too?

People have already started asking these questions following the St. Petersburg metro bombing. What exactly were the security hardliners doing, if not preventing terrorist attacks? If an attack can happen in St. Petersburg, which was under a special security regime because of Putin’s visit on the same day, what could happen in a less secure place?

The fact is that no country, no city, no person can be 100 percent safe from terror. But in Russia, authorities have described their absolute ability to stop terror, making any shortcoming all the more glaring.

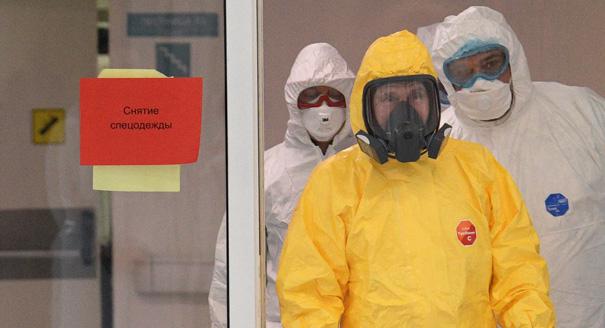

Evidently, the Kremlin understands the seriousness of the problem, but simply doesn’t know how to respond. Vladimir Putin arrived at the scene of the St. Petersburg attack quite unexpectedly—a spontaneity we have not seen from Putin in many years. What’s more, the nightly news following the attack was short on narrative, with information about the perpetrator being disclosed only sparingly.

Still, despite the government’s uncertain response, many Russians still expect the Kremlin to respond with repression, tightening censorship and mass assembly laws.

In the absence of a Kremlin line, pro-government activists and propagandists have taken over the narrative: LifeNews was quick to report that Ukrainians had celebrated the terrorist attack, and experts have rushed to find traces of Western security services’ role in the bombing. The writer Alexander Prokhanov went as far as to associate the attack with the opposition rallies held across the country a week before. Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov, for his part, implored Russians to rally around Putin in the wake of the attack.

Instead of uniting the country, the tragedy in St. Petersburg has become yet another reason to look for enemies and conspirators to blame, once again revealing the deep divisions in Russian society. And it is in the midst of this division that Vladimir Putin enters his 2018 election campaign.