Source: RBC

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has made it clear that he wants to resolve his country’s long-standing territorial dispute with Russia over the Kuril Islands and to prevent an overly close alliance between Moscow and Beijing—and Russo-Japanese relations are heating up as a result.

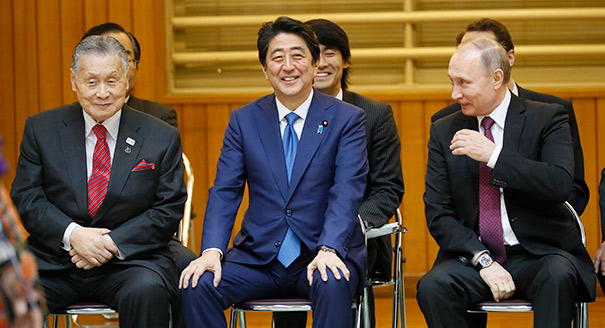

In December, Putin visited Abe in the prime minister’s home prefecture of Yamaguchi. Three months later, the Russian and Japanese foreign and defense ministers met in Tokyo for the first time in almost four years. Then in April Abe visited Moscow, marking only the second time in almost fifteen years that a Japanese premier has made an official visit to Russia.

The Kremlin is not rebuking Japanese diplomatic advances, but it is being more cautious than its counterpart; Moscow wants to improve bilateral relations with Tokyo in other ways before entering into concrete negotiations on the Kuril Islands.

The problem is that Russo-Japanese relations cannot move far beyond where U.S.-Russian relations have been since the 2014 Ukraine crisis: Japan is a close ally of the United States and has been steadfast in complying with all of the G7’s decisions regarding sanctions on Russia.

More than one hundred days into his presidency, Donald Trump has not backed away from the sanctions regime against Russia that Barack Obama introduced. Meanwhile, the results of the French presidential election and the forecasts for the upcoming German parliamentary elections leave no doubt that the countries of the European Union will also maintain sanctions against Moscow. This significantly limits the potential payoff of Russia’s main objective in improving relations with Japan.

This article originally appeared in Russian in RBC.

Still, there are differences between Russia’s relationship with the United States and its relationship with Japan. If Russia is able to emerge from the current crisis and start down the road of economic development, technological cooperation with and investment from Japan will be invaluable for Russia—particularly for Siberia and the Far East.

The key issue is not Tokyo’s willingness to provide resources but rather Moscow’s willingness to embark on a policy of economic development. Although we should not overestimate Russia’s enthusiasm for change in the run-up to the 2018 presidential election or in the period that follows, sooner or later Russia will have to reform its economy and its system of state administration.

The latest rapprochement between Russia and Japan has lasted for almost a year, though Tokyo has changed its priorities recently. Whereas initially Japan emphasized the importance of economic development, its focus has now shifted to security issues.

Prime Minister Abe’s visit to Moscow took place against a background of heightened concerns about North Korea’s nuclear and missile programs. Accordingly, the possibility of a military conflict in Northeast Asia requires a deep, confidential, and candid dialogue between Moscow and Tokyo.

Russia does not hold much sway in North Korea right now, but it could advise Japan on approaches to stabilizing relations and reducing the risk of confrontation, as well as on sensitive points where applying pressure to North Korea would be counterproductive or dangerous. Such a discussion could be more constructive in establishing a new model of Russo-Japanese relations than usual discussions of the U.S. missile defense system in South Korea or the increased presence of Russian armed forces in the region.

In March, representatives of an association of former residents of the southern Kuril Islands visited Russia. Because the local population was evacuated to Japan in 1947, there are few living former residents left. However, their children still honor their ancestors who lived on the islands. Naturally, any solution to the Kuril Islands dispute will not only need to be ratified by the Russian and Japanese parliaments, but also accepted by those countries’ populations.

Thus, in the interests of intensifying relations with Japan, Russia has expressed a willingness to take steps to accommodate the wishes of the former residents of the islands and their descendants. Visa-free travel to the islands, the right to visit Japanese cemeteries, various opportunities for “nostalgia tourism,” and other interactions between Japanese and Russian citizens could create a new fabric of relations and bring the two nations closer together.

Russia and Japan are still early in their journey toward normalizing bilateral relations, and a broader and deeper relationship will take time to develop. However, delays in the process of normalization benefit neither Moscow nor Tokyo, meaning that both sides are looking for regular, tangible achievements sooner rather than later. With this in mind, concrete measures for expanding and strengthening bilateral contacts (whether between diplomats, generals, or representatives of civic associations) present an opportunity to improve Russo-Japanese relations without waiting for top-level decisions to be made.

The objectives of Japan’s “Russia strategy” are evident. Russia’s main objectives are to attract Japanese investment into its national economic development programs and to continue to diversify its policies in the Asia-Pacific and on the international stage, where Japan plays an important and increasingly independent role. The window of opportunity for improving Russo-Japanese relations is still open, at least for now.