The use of technology to mobilize Russians to vote—a system tied to the relative material well-being of the electorate, its high dependence on the state, and a far-reaching system of digital control—is breaking down.

Andrey Pertsev

{

"authors": [

"Christophe Jaffrelot",

"Kalaiyarasan A"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "SAP",

"programs": [

"South Asia"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"South Asia",

"India"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Economy"

]

}

Source: Getty

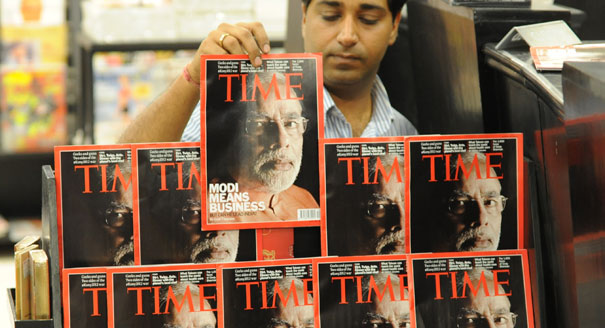

The upcoming elections in Gujarat will be an important test for the Modi government. Many Patels in Gujurat feel alienated and betrayed, but there remain many ardent partisans of the BJP, especially among the elite fractions of the caste.

Source: Indian Express

Given the association of the prime minister with Gujarat, the coming elections in the state will be an important test for his government. While demonetisation and the GST have destabilised the local businessmen, the group the BJP has probably alienated the most is the Patels. After the repression of the movement led by Hardik Patel in the name of reservations in August 2015, the Gujarat government has not found any agreement with the most active Patel organisations, the Patidar Anamat Andolan Samiti and the Sardar Patel Group. On the contrary, in the context of what looks like a tug of war, young Patels, in September 2016, prevented Amit Shah from addressing a rally organised by the BJP to honour the Patel ministers in the then new government led by Vijay Rupani. On September 12, PAAS activists clashed with the BJP Yuva Morcha in Surat again.

Last month, when Narendra Modi was laying the foundation stone of the Ahmedabad-Mumbai bullet train with Shinzo Abe, Hardik Patel conducted a three-day Sankalp Yatra which took him from Ahmedabad to Somnath. In his speeches, he accused the BJP of being responsible for the imprisonment of dozens of Patidars after the August 2015 repression and described it as a party of “dictators and goons.” By contrast, he was soft on the Congress, which, he said, in 1985 — during the repression of the anti-reservation riots in which many Patidars took part — “didn’t kill anybody. But these people killed 14 boys. They don’t have any right to be in power for the next 50 years.” Here, Hardik Patel refers to the casualties of the August 2015 repression and to Amit Shah’s speech in August, when he said the BJP would stay in office not five or 10, but 50 years.

Hardik Patel’s words echo the social media of Gujarat, an arena in which young Patels play a major role. Parallel to the campaign ‘Development has gone crazy’, which shows pictures of undevelopment or maldevelopment across the state, another one, ‘I have been duped’ focuses on promises which have not been kept, like the Metro, jobs or more specifically, Patel-related issues. One slogan says: “They could not give reservation but used bullets and lathis to hit. I have been duped.” Another one, referring to the replacement as CM (in 2016) of Anandiben Patel not by Nitin Patel, but by Vijay Rupani: “They showed us the face of Nitinbhai and delivered Rupani… I have been duped.”

The resentment of the Patels results not only from the attitude of the BJP government, but from their comparatively deteriorating socio-economic condition. There is a paradox here: According to the Indian Human Development Survey, their annual per capita income has jumped from Rs 17,470 in 2004-5 to Rs 51,045 in 2011-12, gaining the top position in the state (the Brahmins, who were number one in 2004-5 with Rs 20,528 have moved to the second position with Rs 44,144). But the Patels who have benefited are not the 40 per cent who till the land (or the 8 per cent who belong to the “casual labour” category), but the 19 per cent who are doing some business and the 19 per cent who are “salaried”. In fact, inequalities have increased more among the Patels than in most other groups, including the Brahmins: The Gini coefficient, between 2004-05 to 2011-12, has jumped from 0.49 to 0.57 when the evolution amongst the Brahmins has been less dramatic (from 0.49 to 0.54) — and the Gini coefficient has even declined among the other forward castes.

It means that the 20 per cent of the richest among the Patels cornered 61.4 per cent of the total Patels’ income in 2011-12 (against 52.8 per cent in 2004-5), whereas the 20 per cent of the poorest got only 2.8 per cent (against 4.1 per cent seven years before). But the poor Patels are probably even more upset because of another development: They are increasingly lagging behind the OBCs and Dalits. In fact, the mean income of the first quintile of the Patels, Rs 3,382, used to be very similar to the mean income of the second quintile of the SCs, Rs 3,643, in 2004-5. Seven years later, the mean income of the first quintile of the Patels, Rs 6,978, was almost half the mean income of the second quintile of the SCs, Rs 11,411. A similar trend is seen in the following quintile. And the fourth quintile of the SCs now earned in 2011-2 as much as the third quintile of the Patels, about Rs 29,000.

What is important here is the trend towards the closing of a secular gap, even more obvious in the comparison between Patels and OBCs. The first three quintiles of the Patels have seen a mean income increase of respectively 106 per cent, 137 per cent and 144 per cent from 2004-5 and 2011-2, whereas the first four quintiles of the Kolis have increased by 74 per cent, 128 per cent, 192 per cent and 204 per cent and the first four quintiles of the other OBCs have increased respectively by 211 per cent, 177 per cent, 170 per cent and 194 per cent. As a result, the third quintiles of the Kolis and of the other OBCs earn almost as much as the second quintile of the Patels and their fourth quintiles almost as much as the Patels’ third quintile.

To compensate for the erosion of Patels, the BJP might woo a section of Kolis and STs who have gained economic mobility in the last decade. The richest quintile among the Kolis cornered 67.8 per cent of the total Koli income in 2011-12 (against 56.5 per cent in 2004-05) which is the highest among the elites of all caste groups. The top income quintile of STs who cornered 57.8 per cent of total tribals’ income in 2011-12 (against 49.7 per cent in 2004-05) in the state might be the other BJP’s target. The party may also use symbols there, by promoting the new president’s caste (he’s a Koli) and inviting the Adivasis to look at themselves as Hindus first. But the loss of the Patels would remain a problem for the BJP, as they reflect societal changes. The figures of the IHPS show that class differentiation is increasing in every caste group and that the upper layers of the lower castes are catching up with the middle-level Patels — hence Hardik Patel’s demand for reservations. These processes have something to do with urbanisation and reservations.

Indeed, the fractions of the caste groups staying in villages are usually losing out. Will class play a role in the coming state elections, like in 2012 when, for instance, urbanised Kolis supported the BJP, whereas rural Kolis stood behind the Congress? Or will caste solidarity prevail? The question is particularly relevant in the case of the Patels who may feel alienated, but among whom there are still ardent partisans of the BJP, especially among the elite fractions of the caste.

This article was originally published in the Indian Express.

Former Nonresident Scholar, South Asia Program

Jaffrelot’s core research focuses on theories of nationalism and democracy, mobilization of the lower castes and Dalits (ex-untouchables) in India, the Hindu nationalist movement, and ethnic conflicts in Pakistan.

Kalaiyarasan A

Kalaiyarasan is faculty at the Institute for Studies in Industrial Development, New Delhi.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

The use of technology to mobilize Russians to vote—a system tied to the relative material well-being of the electorate, its high dependence on the state, and a far-reaching system of digital control—is breaking down.

Andrey Pertsev

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

The pace of change in the global economy suggests that the IMF and World Bank could be ambitious as they review their debt sustainability framework.

C. Randall Henning

As discussions about settlement and elections move from speculation to preparation, Kyiv will have to manage not only the battlefield, but also the terms of political transition. The thaw will not resolve underlying tensions; it will only expose them more clearly.

Balázs Jarábik

Despite considerable challenges, the CPTPP countries and the EU recognize the need for collective action.

Barbara Weisel