Source: Rethinking Russia

Russia “impressed Arab leaders a great deal”

Rethinking Russia: The title of your new book is “What Is Russia Up To in the Middle East?” Well, what is Russia looking for in the region?

Dmitri Trenin: In the terms of the ongoing confrontation with the U.S., Russia is seeking to confirm its great power status. Russian President Vladimir Putin decided to use the tool that he and his predecessors lacked after 1991. This is a military tool.

After all, the Soviet Union was a strong military power and it used its military resources to support, strengthen and increase its political clout. Russia had been lacking this resource for first 20 years after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The 2008 August Russo-Georgian conflict showed to what extent this resource was weak. After this war Putin invested in Russia’s military buildup a lot. By 2015, he acquired a robust military tool.

Putin is a very cautious man, but sometimes he takes calculated risks. And in Syria he took a calculated risk by involving Russia’s armed forces there to increase its status on the international arena. And it was quite successful.

RR: And was this its main success?

D.T.: Russia’s major benefit is the fact that its rivals or former partners see it as a serious power — maybe, this power is not pleasant, it opposes them and destroys the old world order, but it is serious. You can call it a great power, yet today Russia is seen as an important global player.

RR: Ok, the political benefits are obvious, but about the damage? Won’t economic and political damage overshadow those benefits that we’ve already achieved? After all, every success comes with a failure.

D.T.: By the same token, one can say that every failure has a silver lining. Yes, it is the case. But this is not Russia’s first victory. Russia doesn’t have unrealistic commitments. It does have some commitments, which it can fulfill. In fact, it didn’t pay such a big price: It just conducted a military operation within the peacetime budget.

At the same time, Russia was able to test its jet pilots and different arms systems. And this is very valuable. In addition, it is a matter of boosting its prestige.

Look, Americans let down Egypt’s former President Hosni Mubarak, and in a week the demonstration in the Tahrir Square started in Cairo [In the late January 2011, a large-scale rally against Mubarak, who had been ruling the country for 30 years, started, with the protestants requiring his resignation. On Feb. 11, he resigned and handed over his power to Egypt’s armed forces — Rethinking Russia].

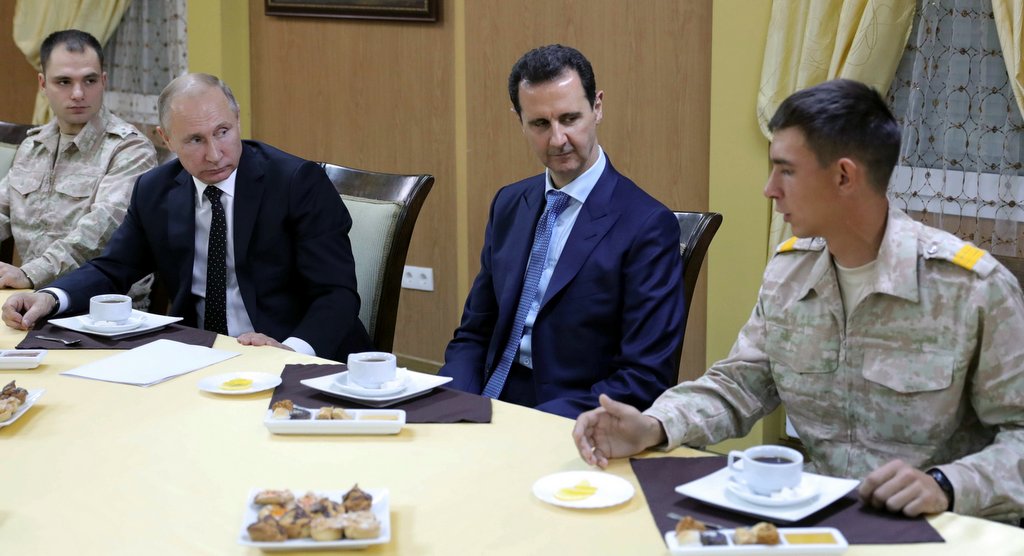

In contrast, Russia didn’t betray its allies and, in fact, it saved Syrian President Bashar Assad, even though everyone buried him. And Moscow dragged him from this difficult situation. And this impressed Arab leaders a great deal.

RR: Do you mean it impressed Russia’s rivals — Saudi Arabia?

D.T.: It impressed everyone. Saudi Arabia didn’t like the way of how Americans behaved during the coup d’état in Egypt, and after it: the U.S. didn’t object to the overthrown of Mubarak and Mohamed Morsi’s ascension to power with his religious party Muslim Brotherhood, which is seen by Saudi Arabia as arch-enemies.

When the U.S. switches from Mubarak to Morsi, it raises some inconvenient questions for the U.S.

RR: Do you mean that one cannot rely on Washington?

D.T.: Yes, of course. They [the U.S.] will betray their allies if the positions of these allies are shaken. It is like in Vladimir Vysotsky’s well-known song “If you’re weak — straight to the grave!” And such behavior does impress as well.

RR: Does this mean that Saudi Arabia sees Russia (not the U.S.) as a mediator in resolving conflicts in the Middle East?

D.T.: Yes, to a certain extent, Russia is seen as a mediator, to some extent it is a counterbalance, to a certain extent it is an alternative force. Take, for example, Turkey: It buys S-400 missile system from Russia not to integrate it into NATO’s system, but to establish it outside the North Atlantic Alliance.

And if the West decides to overthrow the Turkish leadership, these S-400 divisions will defend President Recep Tayyip Erdogan in Ankara, Istanbul or elsewhere, where he might be located. This shield would prevent Turkey’s NATO allies from overthrowing Erdogan. This is very seriously.

Global and fundamental impact

RR: You wrote in your book that Russia’s foreign policy in the Middle East has a global, far-reaching fundamental impact on international relations. Could you clarify this idea?

D.T.: Russia is back as a recognized great power. It is recognized because Russian presidents — from Boris Yeltsin to Vladimir Putin — said in the beginning of their tenures that Russia is a great power. It is engraved in the Russian elite’s mind: “Russia is nothing but a great power. Russia can be only the great power, otherwise it won’t exist.” Yet it is the Russian perception.

The perception of the rest of the world is totally different, and the rest of the world wrote off Russia from the list of important global players. In the 1990s there were talks about the world without Russia, which meant that Russia didn’t exist at all. I do remember how some Western journalists asked me the same question in the 1998: “Well, we know that Russia is disintegrating. Do you think that it will come apart at the seams along the borders of the military districts, because they are the only self-sufficient territorial structures, which could support the vital functions of the country’s regions?”

In the 2010s U.S. President Barack Obama expressed the idea of Russia being a regional power, which could be only a game-changer within the post-Soviet space. Yet outside it Russia doesn’t exist, could not exist and won’t exist.

Putin pulled Russia beyond its borders: Yesterday it was on the periphery, but today it is everywhere. It recruits the U.S. presidents, it determines the outcome of the elections in European countries, it is against the liberal world order and so on.

I don’t say it is good for Russia. This is a mental shift in the perception of Russia, and this is a political shift. The U.S. National Security pays a lot of attention to Russia. Together with China, it is viewed as one of two rivals of the United States. This is the first point.

Second, gradually, the U.S. gives up those positions, which it took after the end of the cold war, as indicated by their response to Russia’s intervention in Syria. They don’t see why they should participate in all global processes. Under Obama and Donald Trump, the U.S. retreated from the Middle East. They fulfill other local tasks, yet they stopped being a power, which determines the order in the region.

The regional order is determined without Washington’s active interference. Yes, the U.S. presence remains in the Middle East, yet they don’t play the same role, which they did under George Bush Junior, Clinton, or Bush Senior. This is a big shift as well.

RR: What did Russia specifically do to provoke this shift?

D.T.: Russia used its force, ignored the American monopoly on the use of power. After all, after the cold war no country could launch a military intervention outside its borders without the U.S. permission. Moscow violated this rule and achieved the results, which it sees as positive.

Second, the U.S. admitted this as a matter of fact — both nominally and through their actions: They didn’t participate actively in Middle East events and didn’t try to push Russia out of the region.

And third, the role of some regional powers — first and foremost, Turkey and Saudi Arabia — increased, and Russia played a role in this as well. Both Ankara and Riyadh are the allies of Washington, but they conduct an independent policy. The U.S. doesn’t control their actions and impose its will. Turkey and Saudi Arabia (as well as Iran, Israel and Egypt) start an active policy, promote their own interests and clash with each other. And this is a very different world.

In addition, Russia together with the U.S.-led coalition defeated the Islamic State of Iraq and Greater Syria (ISIS). I do understand that the Islamic project remains in the minds of people, and it will keep driving them to do something. We could still find a lot on this topic.

But what is important here is the fact that we annihilated what seemed almost invincible in 2014-2015 (after all, the zone of Islamic influence was expanding, everyone was steeping aside, many had to accept their power, the Islamic soldiers were standing 100 kilometers from Baghdad and could impose their control in Damascus at worst). All this will have certain implications for the jihadist movement.

Islamic State still poses a threat to Russia

RR: ISIS is defeated, yet the void might be filled with another radical organization of the same twist. Some experts argue that Hezbollah, a Shia Islamist political party and militant group, which seeks to create a caliphate in Lebanon.

D.T.: Hezbollah existed before, during and after the creation of ISIS. This organization is different. For Israel, Hezbollah does pose a threat and might be even worse than ISIS. But the difference between Hezbollah and ISIS is the former is a regional one, which is based in Lebanon and conducts its activity in Syria.

However, unlike ISIS, it doesn’t seek to establish the global caliphate on all territories, where Muslims live. This is like the difference between national communism and the world revolution: you peruse establishing national communism and don’t go beyond the borders of your country. Yet if you are an advocate of the ideas of the global revolution, you will promote them everywhere.

RR: Yet it is utopic.

D.T.: Yes, it is utopic and, of course, dangerous. It undermines the global stability. And this is what makes ISIS more dangerous for Russia and many other countries than Hezbollah.

RR: What will happen with those Russian citizens, who fought on the ISIS side and might return to Russia? Does this mean that the terrorism threat will increase in the country?

D.T.: I think some of them won’t return. This was one of the goals of the Russian military operation in Syria: stop those who joined ISIS from coming back.

RR: Do you mean they will be annihilated?

D.T.: They have been already annihilated. Russian Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu announced last year that about 2800 citizens of Russia and a certain number of militants from the post-Soviet republics were killed. They fought on the ISIS side.

Some of its supporters turned out to have been disappointed. Some remained intransigent: They (or their relatives and friends) will always fight against Russia. If Russia hadn’t defeated them and they had conquered Syria, the situation would have been much worse: a victory attracts supporters, while a failure leads to the opposite results.

Silence of the U.S. is “the best indication of their recognition”

RR: Previously you told that before Russia’s Syria military campaign, Americans were very skeptical about the results of this operation and compared Syria with Afghanistan, they were speculating about some negative scenarios for Russia. When Moscow proved otherwise, demonstrated its success and bragged about the ISIS defeat, how the U.S. responded — were they surprised, disappointed, envious? Or do they take the wait-and-see approach: “It remains to be seen”?

D.T.: I think today they are not interested in Syria or the Middle East. In 2015 there were different moods in the American establishment, with Obama being criticized for having allowed Russians to take the lead in the Middle East. Today, the U.S. is fully obsessed with the investigation into the Kremlin’s alleged interference in the 2016 presidential election and the Trump administration’s ties with Russia. So, today the situation is different.

In fact, the U.S. accepted Russia’s success in the Middle East as a matter of fact without thinking too much about it. If you were an opponent of Trump, you would accuse him of letting Putin to be a winner in Syria. Yet if you are a Republican and if you support Trump, you will say that Obama is the origin of the problem, because he allowed Russia to take the lead in Syria.

Silence of the U.S. is the best indication of their recognition. After all, when the West is silent, this might mean that it accepts something unpleasant, it just takes it into account: “Don’t expect us to welcome your success. We accept it, yet we won’t congratulate you”.

RR: Russia, Turkey and Iran are cooperating on the Syrian question within the Astana format. In 2017, there were seven rounds. In your view, to what extent is the Moscow-Ankara collaboration robust, taking into account the Russian-Turkish rivalry in the Middle East? After all, Moscow and Ankara disagree on the Kurdish question (Russia supports them) and Nagorno-Karabakh. In 2015, the cooperation between the countries was interrupted in no time, after Turkey shot down a Russian jet over the Syrian-Turkish border.

D.T.: I think Russia is in a stronger position now than Turkey. Turks will take this fact into account. Regarding Russia, it will draw a line between Turkey’s legitimate interests and their geopolitical ambitions. I don’t think that Russia is interested in destroying the Turkish statehood. I don’t think that Russia is interested in supporting the undermining activity of Kurdistan Workers’ Part, which is deemed as a terrorist organization by the Turkish government. I don’t think that Russia is interested in creating another hotbed of tensions by strengthening the Kurds.

On the other hand, Russia doesn’t want Turkey to impose its influence in Syria. In this situation, there could be a balance between what is seen as legitimate and what is seen as ambitious. I don’t know how we could achieve it, but the idea of the Syrian federalization, which suggests creating a Kurdish quasi-state on the Syrian-Turkish borders, is not effective. Russia absolutely doesn’t want it, while Kurds might be interested in it. A compromise for Russia could be the creation of autonomy in this situation.

RR: You told that Russia’s Syria campaign is a chapter in the book, not its end. Does it mean that Russia will get stuck in Syria for a long time?

D.T.: Russia will remain in Syria by maintaining its military presence and political clout there: there will be Russian aviation, military bases and vessels there. In this regard, Russia will get stuck in Syria for a long time. Yet it is a rather positive aspect.

RR: What about a negative aspect?

D.T.: So far, I don’t see who may become a serious opponent to Russia in Syria. If we assume that the U.S. will decide to change their policy in the Middle East and start strengthening the Syrian opposition to overthrow Asad, we might face with the American allies, I mean the Sunni states. This means that we will fight against a country, supported by the U.S.

RR: How do you see the prospect of the Russian-American collaboration in the Middle East in this situation?

D.T.: To a certain extent we are cooperating with the U.S. This collaboration might even continue. If Syria doesn’t become a top priority for the U.S., we will avoid the clash. If Syria becomes a priority for Washington (which is hardly likely now), there might be a harsh confrontation. We need to avoid it.

This interview was originally published on “Rethinking Russia”