In an interview, Naysan Rafati assesses the first week that followed the U.S. and Israeli attack on Iran.

Michael Young

{

"authors": [

"Erik Brattberg",

"Philippe Le Corre"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Europe"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "asia",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "AP",

"programs": [

"Asia",

"Europe"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"East Asia",

"China",

"Western Europe",

"Germany",

"Asia",

"Europe",

"Iran"

],

"topics": [

"Economy",

"Trade",

"EU",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

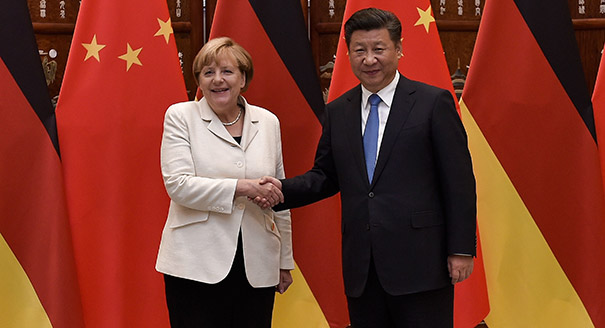

Source: Getty

As President Trump continues to disregard European concerns, Germany feels the need to cultivate better relations with China, with an understanding of the pitfalls and limitations of working with Beijing.

Source: South China Morning Post

Over the past year, Berlin has toughened its stance on China as German business and political elites’ concerns about Chinese economic practices, including in Germany itself, have intensified. But during Angela Merkel’s trip to Beijing this week – her eleventh as chancellor – she struck a more conciliatory tone.

Merkel remarked that both Germany and China wanted a rules-based, fair free trade system and that she wanted to work with Beijing to “strengthen multilateralism”.

The backdrop to Merkel’s attempt to improve relations with China is Donald Trump’s unwavering protectionist and unilateralist policies on things like steel and aluminium tariffs and the withdrawal from the Iran nuclear deal.

Until recently, Merkel and some European leaders still harboured a hope that the mercurial US president could be swayed on central issues. This dream is now shattering as Trump repeatedly shows a willingness to disregard European concerns.

As a result, Germany feels the need to hedge against America’s increasingly reckless policy by cultivating stronger ties with other major players. Enter China.

Germany and China both have faced attacks from Trump for running trade surpluses against the US. The main difference is that whereas President Xi Jinping and Trump have a strong personal relationship, Merkel has struggled to get along with America’s chief executive.

China, moreover, has been able to leverage the North Korean crisis to ease some of Washington’s pressure on trade issues, whereas Trump has repeatedly doubled down on Germany.

Merkel’s Beijing trip, therefore, was intended as a push on behalf of German business for greater access to China’s markets.

China still ranks only fifth among Germany’s largest export centres, but its share is growing and will become increasingly important, especially if the American marketplace becomes more closed for German products such as cars.

The US Commerce Department’s announcement that it is considering imposing additional tariffs on imported vehicles reinforces that assessment.

But Merkel is also walking a fine balance. While she hoped to send Washington a message of German-Chinese unity to push the Trump administration to abandon its controversial trade policies, the chancellor also understood well the pitfalls and limitations of working with China.

In addition to trade, she looked to get support from China for the EU’s attempts to keep the Iran nuclear deal alive after the US pull-out. Since the Trump administration seems bent on aggressively going after European businesses in Iran, China could step in to fill some of the void to give Tehran an incentive to remain part of the deal.

While it is understandable that European capitals want to improve relations with China when transatlantic relations are in shatters, most German elites think it is an illusion to believe Beijing can constitute an alternative to Washington.

In reality, despite Trump’s protectionist trade policies and unilateral foreign policy decisions, Beijing is a far worse offender when it comes to challenging the rules-based international order. For example, in July 2016 it rejected the ruling of the international arbitration court of The Hague on the South China Sea and declared it would exclusively follow Chinese regulation.

The paradox is that the US and Germany increasingly share common concerns regarding China.

The US Congress and the European Parliament both are finalising tougher regulations vis-à-vis Chinese investment in sensitive technology and infrastructure. In Washington and Brussels, political elites keenly demand more reciprocity and market access from the Chinese side.

Yet, this common analysis has not translated into practical cooperation. Despite the US national security strategy’s call for greater collaboration with America’s friends and allies on addressing China, Trump has repeatedly rebuffed European overtures to Washington on coordinating approaches.

In many ways, this has to do with the US president’s inability to distinguish between friends and adversaries in the first place. In Trump’s skewed, zero-sum world view, Germany is as bad a trade offender as China – if not even worse.

For China, this is mostly good news. While Beijing is still concerned with the prospect of a greater transatlantic resistance against its economic policies, Merkel’s change of tone gives China a window of negotiation, just weeks before the EU-China summit next July.

Although Germany remains fundamentally a pro-transatlantic country, the contentious Berlin-Washington relationship is a welcome gift for China, which will be able to excel at its favourite game: playing countries against each other.

This piece was originally published in the South China Morning Post.

Former Director, Europe Program, Fellow

Erik Brattberg was director of the Europe Program and a fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington. He is an expert on European politics and security and transatlantic relations.

Former Nonresident Senior Fellow, Europe Program

Philippe Le Corre was a nonresident senior fellow in the Europe Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

In an interview, Naysan Rafati assesses the first week that followed the U.S. and Israeli attack on Iran.

Michael Young

With the White House only interested in economic dealmaking, Georgia finds itself eclipsed by what Armenia and Azerbaijan can offer.

Bashir Kitachaev

If the succession process can be carried out as Khamenei intended, it will likely bring a hardliner into power.

Eric Lob

But to achieve either, it needs to retain Washington’s ear.

Alper Coşkun

At heart, to impose unconditional surrender on Hezbollah and uproot the party among its coreligionists.

Yezid Sayigh