Andrey Pertsev

{

"authors": [

"Andrey Pertsev"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [

"Inside Russia"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

System Failure in Russia: The Elections That Didn’t Go as Planned

The Kremlin obviously understands that elections held under the old rules will result in more defeats. The rules, therefore, will have to change. Just like in 2013–2014, when opposition candidates started winning mayoral elections, the Kremlin first welcomed their victory, but then dispatched local legislatures to scrap mayoral elections altogether. They remain in just seven out of 83 regional centers. A similar fate may now await gubernatorial elections.

It had seemed that in the six years since gubernatorial elections were reintroduced in Russia, the Kremlin had come up with the perfect formula for holding them. Municipal filters, in which candidates must collect a certain number of endorsements from local council members in order to run, deals with in-system opposition parties, administrative pressure, and the president’s personal support all previously ensured that even the regime’s weaker candidates would win the first round of elections, while strong ones swept to victory with up to 70–80 percent of the vote. But this year’s regional elections, in which the authorities failed to secure their candidates’ victories in as many as four regions, have demonstrated that the established scheme no longer works.

It’s no longer true that the candidate backed by the regime is guaranteed to triumph over a symbolic opponent. The Communist Party municipal legislator Valentin Konovalov won the gubernatorial elections in Khakassia, while Vladimir Sipyagin, a Duma deputy for the LDPR, defeated the incumbent governor the Vladimir region. Few people had even heard of the Communist candidate in the Primorsky region, Andrei Ishchenko, before he ran for governor, yet for a long time he was in the lead in the subsequently annulled runoff. Weak candidates who didn’t even campaign properly—with the exception of Konovalov—have managed to cause problems for the regime.

In other regions such as Krasnoyarsk, Amur, and Altai, regime candidates won, but with nowhere near the strong results that were previously expected, even faced with weak opponents. Traditional images of “local candidate,” “young technocrat,” or “powerful lobbyist” no longer matter. People only sее one label—“regime candidate”—and vote against them.

Support from the federal center and even personally from President Vladimir Putin doesn’t work now, either. The president had met before the first round of the election with all the candidates who were then forced into a runoff, but those meetings clearly failed to work their magic, even though the federal authorities promised new projects, greater funding, and other incentives.

Deliberate reminders of support from above, such as the seal of approval: “Approved by the President” on campaign posters urging Khakassians to vote for regional governor Viktor Zimin, had no effect.

Strategists for regime-backed candidates openly state that the plans to increase the retirement age in Russia were a catalyst for protest voting, along with other causes for discontent: impending tax hikes, social issues, and price increases. The regime candidates’ second-round losses are a rebuke to the Kremlin.

Pro-regime analysts may explain the results away as individual cases and allude to the penchant for protest in the Far East, but the outcomes were too diverse to be limited by those factors. After all, this is not just about the four regions that had runoff elections. The Communists also did unexpectedly well in municipal elections, and A Just Russia candidate Alexander Burkov in Omsk and Communist Andrei Klychkov in Oryol had the best showings overall in gubernatorial elections, winning 82.5 percent and 83.5 percent of the vote, respectively. Just like United Russia candidates in other regions, they faced no serious challenge, but their impressive numbers also resulted from their vocal opposition to pension reform.

Local elites have a lot to ponder now. It seems it’s quite easy nowadays to get an outspoken politician elected if they run as a candidate from an in-system political party and convince the local administration that they are harmless before conducting a well-funded campaign. Against the backdrop of popular discontent, regional elites may ask themselves why they even need to deal with the ruling party.

In this atmosphere, even the perennially loyal LDPR has started showing an independent streak. At first, its candidates barely campaigned in the runoff votes, and the Khabarovsk candidate, Sergei Furgal, docilely accepted the governor’s offer to become his first deputy. But by the end, the party had sent its observers to the polls and even started saying it might not recognize the outcome of the election: a claim it naturally withdrew after Furgal won the runoff.

The only maneuver that the center could come up with to at least technically avoid a defeat was to invalidate the election results as it did in the Primorsky region, citing numerous violations. But it would be absurd to apply this method all the time. The authorities didn’t dare to do the same in Khabarovsk and Vladimir, where politicians who didn’t even want to win have ended up at the helm. If such candidates keep winning, it will be increasingly difficult to manage the country.

It’s hard to imagine that the Russian authorities will give up their Putin-centric approach to regional elections. Regional elections won’t suddenly become relatively competitive, nor will the regime agree to work with the in-system opposition governors.

It’s more likely that the system will make every effort to preserve its core, where Putin and the center make all the decisions. We can already see how pro-regime media outlets and bloggers are attempting to justify the regional election results, attributing the losses to controlled democratization and mistakes made by local governments. However, the scale of the defeat and the regime’s subsequent reaction discredit both of these justifications.

The Kremlin obviously understands that elections held under the old rules will result in more defeats. The rules, therefore, will have to change. Let’s recall the events of 2013–2014, when opposition candidates started winning mayoral elections: Galina Shirshina in Petrozavodsk, Anatoly Lokot in Novosibirsk, and Yevgeny Roizman in Yekaterinburg. The Kremlin at first welcomed their victory, but then dispatched local legislatures to scrap mayoral elections altogether. As a result, they remain in just seven out of 83 regional centers.

The simplest first step that the authorities can take now is to get rid of the second round for gubernatorial elections, just as was done with mayoral elections in the past. After all, the regime candidate almost always wins the simple majority in the first round. One round of voting also makes it easier to weaken the leading opposition candidate’s showing by introducing spoilers. But this move might not help in the long run: even now, two of the four in-system opposition candidates that forced runoffs won a simple majority in the first round. And the protest vote is bound to grow as public discontent strengthens.

Scrapping gubernatorial elections altogether seems like a more reliable option. The election news coverage on federal TV channels indicates that the central government is indeed considering this option. News reports emphasize numerous electoral violations by opposition parties, although regional governments also come under fire. Even the perfect candidate supported by the president can be tarnished by the cesspool of public politics, the logic goes. Hence, we don’t need elections.

Abandoning direct gubernatorial elections delivers tactical advantages, but no one knows what the strategic consequences might be. The unpredictable election results have piqued public interest and become front-page news. Scrapping the elections will elicit a negative reaction, although to what extent is still unclear. It may well result in protest that will attract local elites and in-system opposition parties that will smell blood.

About the Author

Andrey Pertsev

Andrey Pertsev is a journalist with Meduza website.

- The Kremlin Is Destroying Its Own System of Coerced VotingCommentary

- Why Is the Kremlin Punishing Pro-War Russian Bloggers?Commentary

Andrey Pertsev

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- My Country, Right or Wrong: Russian Public Opinion on UkrainePaper

Rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict in Ukraine has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect.

Denis Volkov, Andrei Kolesnikov

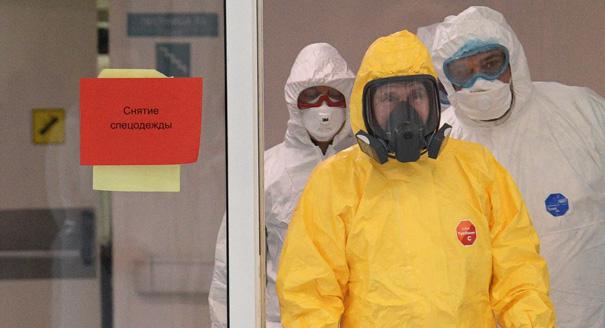

- As Putin’s Regime Stifles the State, the Pandemic Shows the CostCommentary

Russia’s ineffective response to the coronavirus reveals the hazards of a system that cultivates self-interest and cronyism over strong state capacity and administration.

Nate Reynolds

- Facing a Dim Present, Putin Turns Back To Glorious StalinCommentary

The foundation of the current Kremlin ideology is a defensive narrative: that we have always been attacked and forced to defend ourselves. Another line of defense is history.

Andrei Kolesnikov

- The Putin Regime CracksArticle

The pandemic has revealed a truth of the Russian government. Vladimir Putin has become increasingly disengaged from routine matters of governing and prefers to delegate most issues.

Tatiana Stanovaya

- Russia’s Leaders Are Self-Isolating From Their PeopleCommentary

The fight against the new coronavirus in Russia is being led not by politicians oriented on the public mood, but by managers serving their boss. This is why the authorities’ actions appear first insufficient, then excessive; first belated, then premature.

Tatiana Stanovaya