The latest ruling in the Moscow protest cases sent a clear signal, and not just to society.

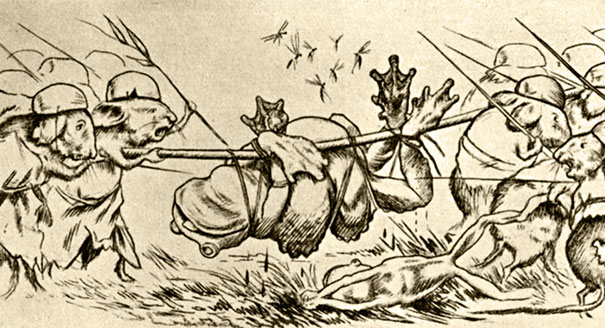

On Friday, Yegor Zhukov, a student, was found guilty of public incitement to extremism in his video blog, and given a three-year suspended sentence. But what’s really interesting about this case is Judge Svetlana Ukhnaleva’s additional sentence: she ordered the destruction of three ceramic frogs.

Ironically, the means of the crime—a camera and computer—were returned to Zhukov, while a yellow libertarian flag and the ceramic model of a family of three frogs that was standing on Zhukov’s desk in his videos were ordered to be destroyed.

Why did Judge Ukhnaleva hand down such a bizarre ruling? She is no novice, and doesn’t need to focus on forging a professional name for herself: she is already at a senior level. In condemning the frogs to execution, Ukhnaleva was sending a signal—to the people who introduced the frogs into the case in the first place: investigators and prosecutors, who kept returning to the sacred nature of the frog family during the trial.

Zhukov was first accused of taking part in mass rioting, then of making a video blog in which an FSB expert (an engineer by education) identified signs of extremism. Faced with a lack of any evidence of wrongdoing, the prosecutor focused on the frogs.

In passing down her sentence, it looks very much like Judge Ukhnaleva was also passing judgment on the work of investigators and prosecutors. Judges are deeply unimpressed with the quality of investigations, which are forcing the judges to take extreme positions. The frogs are a form of protest for Ukhnaleva. To find the defendant guilty without permission from above would have been too much, so she worked with what she had.

A total of seven sentences were handed out over the Moscow protests on Friday, December 6. All were found guilty, and three were given prison sentences. Nikita Chirtsov, a twenty-two-year-old internet entrepreneur, got a year in prison for pushing a policeman. The judge in his case was Elena Bulgakova, who back in August sentenced another Moscow protester, Danila Beglets, to two years in prison for using violence against a representative of authority.

Crucially, Chirtsov pleaded not guilty, which means his case is not over. He can appeal, seek a reversal, and take it all the way to the European Court of Human Rights. This is worth pointing out at every opportunity: if the defendant pleads guilty, then the option of appealing the verdict is closed to them. This came as a shock to many of those facing charges over the Moscow protests: Beglets, for example, simply didn’t know this, and was persuaded by lawyers to plead guilty, without being told the full implications.

Another person sentenced over the Moscow protests on Friday was Pavel Novikov, who pleaded guilty and got off with a fine of 120,000 rubles ($1,895). Novikov was accused of hitting a police officer on the shoulder and helmet with a bottle of water. Beglets, on the other hand, is serving a two-year sentence for pulling at the uniform of a law enforcement officer. The unexpectedly “light” sentence given to Novikov can only be explained by the amount of attention that Beglets’s case attracted.

Another of the defendants, Vladimir Emelyanov, was accused of grabbing a National Guard officer by their body armor. The officer in question even requested that Emelyanov should not be punished, but he had still been kept in pretrial detention since the middle of October. By the time of the trial, it had become widely known that Emelyanov was an orphan, and was responsible for caring for his seventy-two-year-old grandmother and ninety-two-year-old great-grandmother. Until recently, these circumstances would not have concerned the Russian justice system, but on Friday, Emelyanov was given a suspended sentence.

The same day, Maxim Martintsov was given two and a half years for kicking a police officer. Alexander Mylnikov, the father of three children for whom he has sole responsibility, got a two-year suspended sentence for exactly the same charges.

Something has obviously changed in the legal system, and that something is the logic of repression. As recently as three months ago, everyone was being given prison sentences, as judges tried to gauge the leadership’s mood and bore the example of the Bolotnaya case in mind. Neither the existence of young children nor aging relatives, and certainly not the lack of a crime, could influence this. Now the changes are there for everyone to see.

Kommersant newspaper had a very interesting account of how things had unfolded. “According to one source close to the Kremlin, officials were closely monitoring attitudes to the Moscow protest cases among the public. They could not fail to take into account the large-scale and high-profile campaigns in support of many of those detained in the case, including the actor Pavel Ustinov, who was sentenced to three years in prison [that sentence was later overruled and he was given a one-year suspended sentence]. Professional solidarity also plays a role. Many actors spoke up for Ustinov, while students and representatives of universities rallied around Zhukov,” a student at Moscow’s prestigious Higher School of Economics.

A source close to the Presidential Human Rights Council spoke to Kommersant of “closed social surveys” that were apparently carried out at the request of the presidential administration.

“They showed that public opinion was not on the side of the authorities’ position,” the source was quoted as saying. The source told Kommersant that such closed polls are carried out regularly by the state pollster VTsIOM. This one showed that people “didn’t particularly express their support for Yegor Zhukov, but no one expressed any malice or bloodlust in his regard either.”

These rumors only confirm a general feeling that despite all the skepticism, public opinion does play a role in the decisionmaking over the degree of repression in each particular case. Public support, attention to the case, the involvement of high-profile people, and professional solidarity—especially the opinion expressed by representatives of the Orthodox Church, for the first time in recent history—are all important. They can be measured in the number of years in prison to which individual defendants in the Moscow protest trials are not sentenced, thanks to public support—or to which, in its absence, they are condemned.

Judges don’t want to get involved with high-profile cases, and will seize any opportunity to take it out on the prosecutor’s office, like Judge Ukhnaleva did so exquisitely with the frogs. This is the important political leitmotif of the end of the year.

It’s perhaps worth repeating that anyone who is not guilty must defend themselves. A guilty plea makes life easier for the judge and investigators, and means the defendant will get a longer sentence. It also puts an end to the prospect of finding a way out via the law.

Another important thing to note is that it is useful to tell the truth. If someone facing charges in a political case says in court that they had simply gone for a walk or popped outside to smoke when they were suddenly arrested for no reason, they will—if convicted—be considered as wrongly convicted (if, of course, it was the truth). If that person kept a political blog, attended protest marches and one-person pickets, and is being charged over those activities, then they become a political prisoner. That is the difference, and it’s an important one to know.

The judges certainly know it, so there is no getting around the fact that Zhukov is a political prisoner, as opposed to someone who pleads guilty or says that they had simply gone for a walk. This also explains the difference in coverage and attention paid to various legal cases. And attention, crucially, is something that now even the presidential administration recognizes.