- +11

Frances Z. Brown, Nate Reynolds, Priyal Singh, …

{

"authors": [

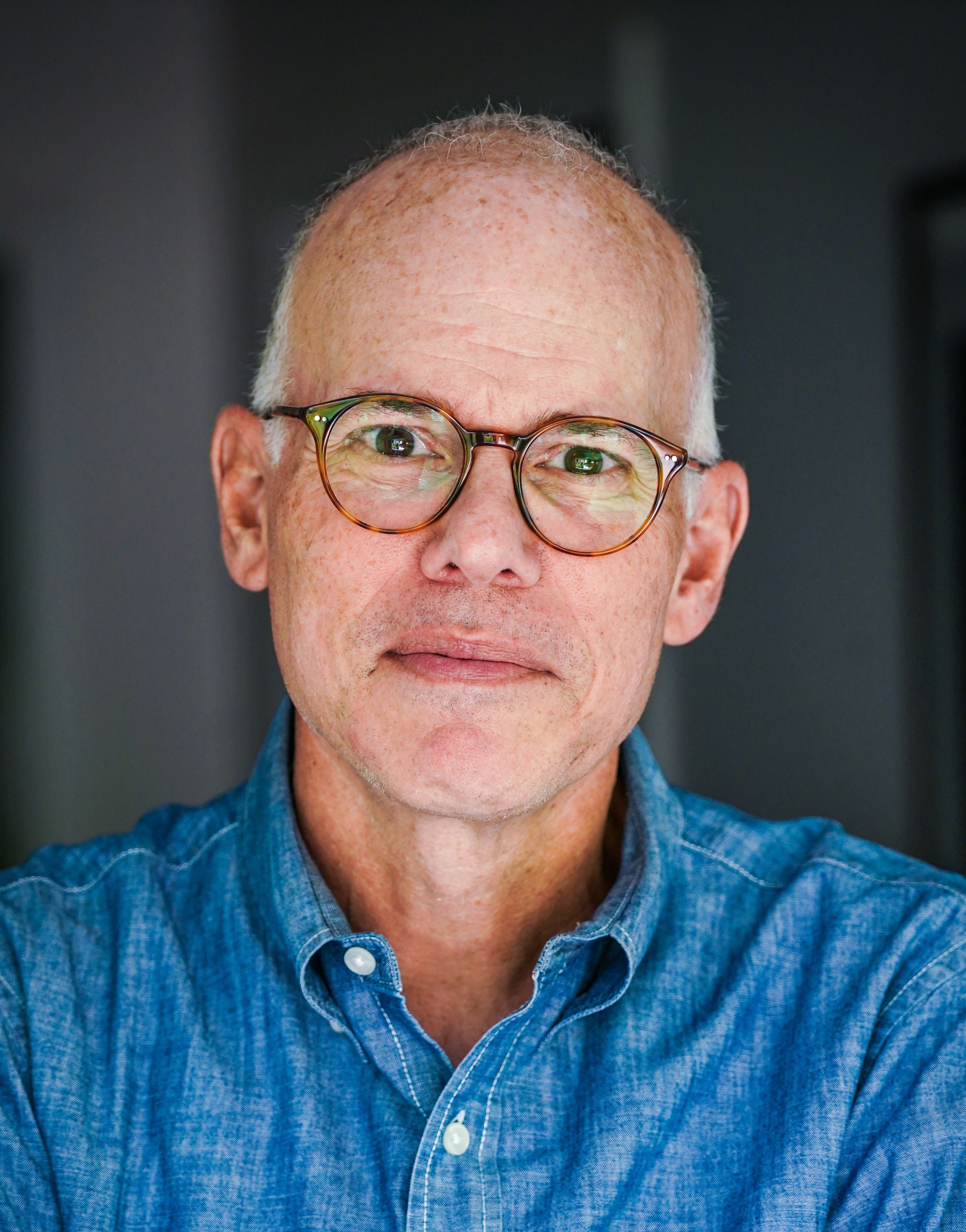

"Frederic Wehrey"

],

"type": "commentary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [

"The Day After: Navigating a Post-Pandemic World"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "ctw",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "russia",

"programs": [

"Russia and Eurasia",

"Middle East"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [],

"topics": []

}

Source: Getty

View From Libya

Putin has dispatched mercenaries to Libya’s civil war, exploiting the protracted conflict to carve out a new sphere of influence in North Africa.

It was the mortar rounds that worried Muhammad the most. They fell with a frequency he’d never encountered. “Like rain,” he said.

Then there were the snipers. Their shots were terrifyingly accurate and used a type of bullet new to the Libyan battlefield.

It was an overcast evening in November 2019. I sat with Muhammad, a militia commander and former engineer in his late forties, in a farmhouse outside the Libyan capital of Tripoli. For months, he and his men had been waging a grinding war against forces led by a renegade general named Khalifa Haftar, who was trying to topple the country’s internationally recognized government.

It had been a static battle whose frontlines barely moved. But in September, Haftar had gained momentum. His firepower became more lethal. His emboldened men seized new territory.

The sudden shift was the handiwork of hundreds of Russian mercenaries from the Wagner Group who had arrived to bolster Haftar’s troops.

An ostensibly private military company, Wagner has, in fact, served as an important tool of power projection for Russian President Vladimir Putin. It has been deployed across the globe, from the Central African Republic and Mozambique to Syria and Ukraine.

The results of these adventures have been mixed. In Libya, however, the Wagner Group made a difference. Morale among the government forces plummeted. Capturing Tripoli appeared within Haftar’s grasp.

This wasn’t the first time that Russia had helped Haftar. Drawn by the promise of energy control and arms deals in this oil-rich state, Moscow had courted and aided the Libyan general for years. All the while, it kept open channels to his government rivals.

To counter the Wagner deployment last fall, the Libyan government turned to Turkey for help. In December, Ankara deployed thousands of Syrian mercenaries to Tripoli—along with advisers, air defenses, artillery, and drones. Aided by this influx, government troops pushed Haftar’s forces out of the capital region.

Moscow quickly pivoted, dispatching advanced combat jets to Haftar’s territory in the east. In tandem, Wagner forces were redeployed across the east and south, including to strategic oil fields.

These moves were part of a broader Russian strategy to gain leverage for a political settlement with Turkey that would establish economic and military spheres of influence while undercutting Europe and the United States. And they starkly illustrated how an opportunistic and scalable military intervention could yield modest strategic gains for Russia.

But the Libyan conflict has carried incalculable human costs. Haftar’s forces are responsible for indiscriminate attacks on civilians, according to the United Nations.

Meanwhile, Western powers have largely stayed on the sidelines. The U.S. President Donald Trump’s administration has tacitly endorsed the Libyan general’s assault. Washington is growing frustrated with Haftar’s blockade of oil facilities and alliance with Russia, yet the White House continues to downplay the destructive role of U.S. allies—including Egypt, France, and the United Arab Emirates—in fueling his campaign. France has admonished Turkey for intervening while ignoring the Emirates’ longstanding interference, but Europe as a whole has been too divided and distracted to engage.

For Muhammad, the progovernment Libyan commander, U.S. ambivalence has been especially bitter.

Several years ago, he and the Tripoli government forces received U.S. military aid during a campaign against the self-proclaimed Islamic State. Now they feel abandoned.

“Russia gave Haftar mortars,” he said. “What did Trump give us?”

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Middle East Program

Frederic Wehrey is a senior fellow in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where his research focuses on governance, conflict, and security in Libya, North Africa, and the Persian Gulf.

- Russia in Africa: Examining Moscow’s Influence and Its LimitsResearch

- How the Flaws of Trump’s Gaza Deal Prevent an Enduring PeaceCommentary

Charles H. Johnson, Frederic Wehrey

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- India’s Path to the Big LeaguesCommentary

India can play a larger role on the world stage, but it must first restore its economic momentum and liberal credentials.

Ashley J. Tellis

- A Coming Decade of Arab DecisionsCommentary

As the old order in the Arab world collapses, the region needs governance that can resolve its crises and harness its potential.

Marwan Muasher, Maha Yahya

- Reckoning With a Resurgent RussiaCommentary

The greatest obstacle to countering Russia’s hard-edged foreign policy has been the West’s incoherent response.

Andrew S. Weiss, Eugene Rumer

- A U.S. Foreign Policy for the Middle ClassCommentary

The United States must secure the benefits of a globalized economy while protecting itself from systemic shocks and supporting the economic renewal of middle-class communities.

Rozlyn C. Engel

- Asia’s Future Beyond U.S.-China CompetitionCommentary

Beijing and Washington are competing to set Asia’s rules, norms, and standards. But other countries in the region are increasingly choosing to shape its future themselves.

Evan A. Feigenbaum