The U.S.-China trade war and the coronavirus pandemic have exposed supply dependencies and provoked a reevaluation of supply chains centered on China. A nationalist view of supply chains motivates President Donald Trump’s tariff-centric strategy to reduce the United States’ trade deficits and rejuvenate its economy. Yet the trade war’s impacts are the opposite of the White House’s intentions. Tariffs produced no real improvement in the underlying balance of U.S. trade, while China’s overall trade surplus increased 20 percent and its export markets became more diversified.

Tariffs produced no real improvement in the underlying balance of U.S. trade.

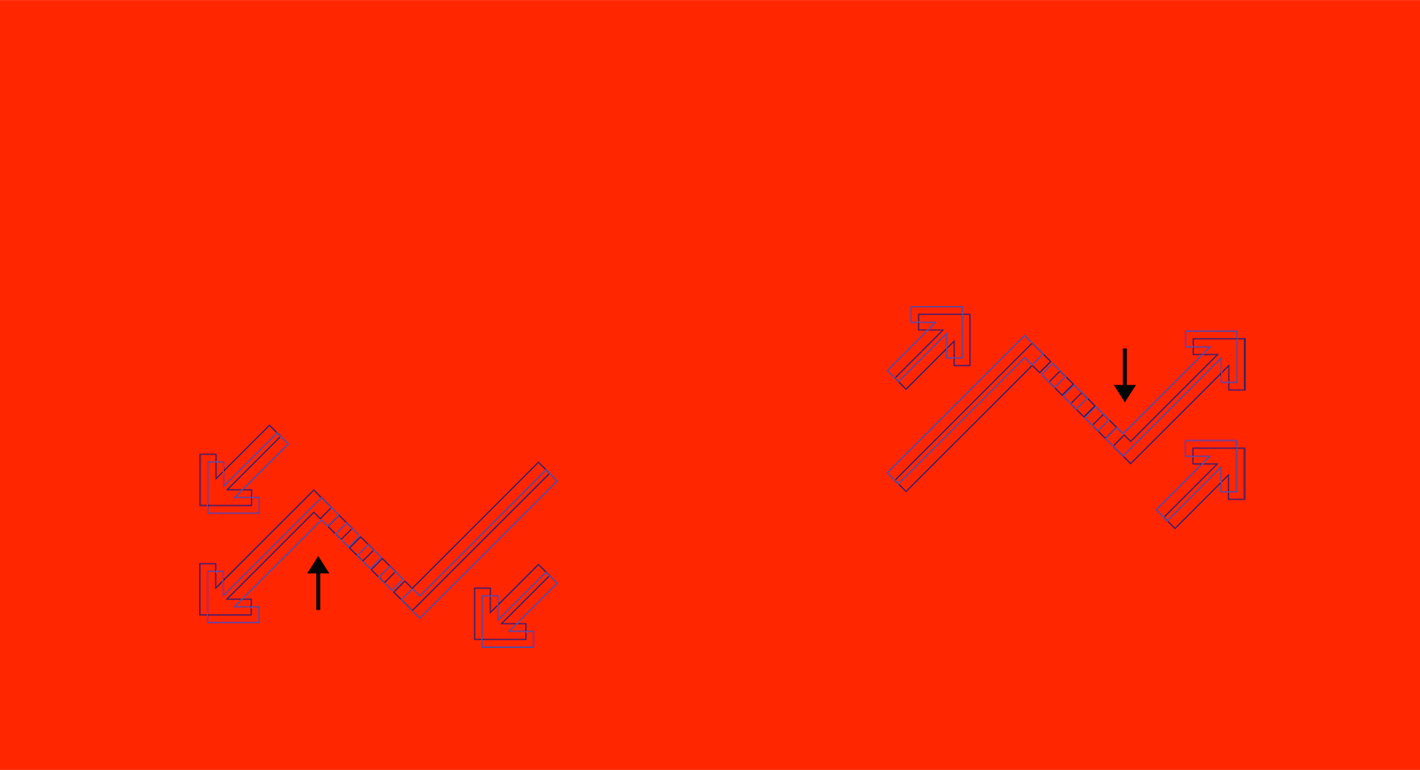

In 2019, U.S. merchandise imports contracted from their 2018 levels by $44.3 billion (see figure 1). A sharp $87.3 billion drop-off in imports from China drove the decline, as tariffs are currently in place on about $370 billion in U.S.-bound Chinese goods.

Among the economies within Asia that have benefited from the trade war, the undisputed winner is Vietnam (up $17.5 billion). Taiwan, to a lesser extent, also benefited. Europe and Mexico filled much of the gap, as their respective exports to the United States rose by $31.2 billion and $11.6 billion. Notably, imports from Venezuela and the Middle East and North Africa plummeted as a result of U.S. sanctions and increased energy self-sufficiency.

On the exports side, the United States was hurt by retaliatory tariffs imposed by China and other countries subject to U.S. duties on steel and aluminum. Rather than increasing the competitiveness of U.S. producers, those tariffs led to a net decline of $23.1 billion in exports. Trump did shrink the bilateral trade deficit with China but did so at the cost of a significant contraction in economic activity. If not for the reduction in oil imports, the United States’ trade deficit would have widened.

Despite Trump’s vision of a “blue-collar boom,” U.S. domestic manufacturing did not pick up the slack.

Moreover, despite Trump’s vision of a “blue-collar boom,” U.S. domestic manufacturing did not pick up the slack. The industrial production index declined for the first time since 2015 in response to supply chain interruptions and increased production costs attributable to tariffs. This yielded a welfare loss in the form of forgone consumption due to higher prices, undercutting the president’s mistaken but oft-repeated claim that China, not the United States, is paying for the tariffs.

How has China responded? Unsurprisingly, exports to the United States and Hong Kong—an intermediary hub—declined significantly as a result of tariffs. However, China ramped up sales to nearly everyone else, especially trading partners in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations and in Europe, containing the contraction in overall exports to just $2.8 billion (see figure 2).

Chinese imports from the United States fell by $33 billion in 2019, as did imports of no-longer-needed components from Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan given the decrease in manufactured exports to the United States. This led to a sharp decline in total imports and an improvement in China’s overall trade balance of over $60 billion last year, despite the trade war.

These ripple effects underscore the fact that—contrary to the misguided view of the White House—trade is a multilateral phenomenon. Trump’s protectionist policies, which threaten to escalate ahead of the November 2020 presidential election, may be shaking up supply chains, but they will neither moderate U.S. trade deficits nor weaken China’s economy.

Nevertheless, some degree of economic decoupling is underway, especially as the pandemic encourages the United States and other countries to become less dependent on China for medical supplies. While the extent of this shift is debated, the bolder predictions may be overblown. China’s cost advantages—including strong infrastructure, skilled labor, and readily available essential components—cannot easily be matched elsewhere. Tellingly, an American Chamber of Commerce in China survey conducted in May 2020 found that a mere 4 percent of firms had considered relocating some or all of their manufacturing out of China.