Dan Baer, Sophia Besch

{

"authors": [

"Dan Baer"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "DCG",

"programs": [

"Democracy, Conflict, and Governance"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Political Reform",

"Democracy",

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

Source: Getty

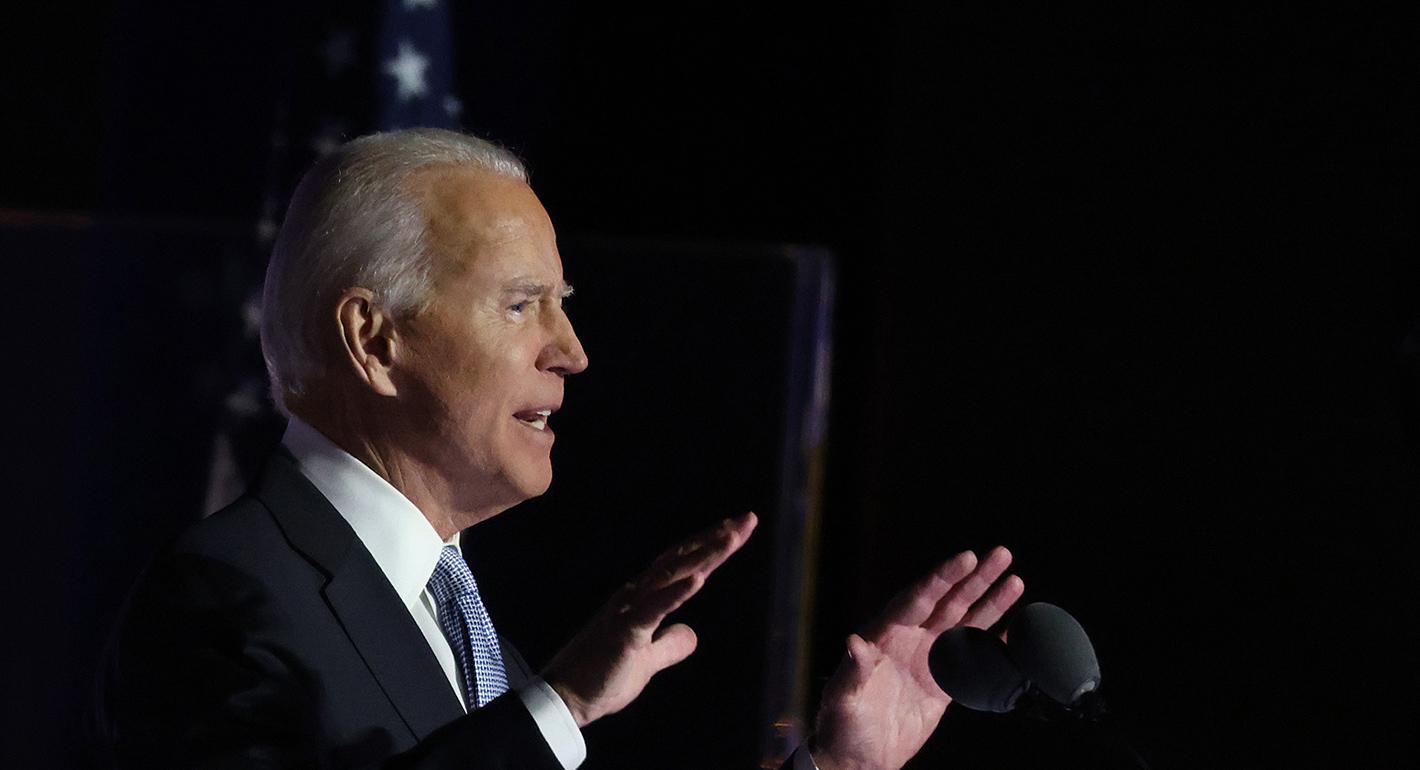

Note to U.S. Allies: America Will Remain Divided and Frustrating

For U.S. allies and partners around the world, the United States will stop being an at times gratuitous antagonist, and the Biden-Kamala Harris administration will reinvigorate U.S. diplomacy, but Washington will remain a frustrating partner on important issues.

Source: Foreign Policy

Let’s start with a positive note: It is a good thing that we do not know the outcome of U.S. elections before they happen. Democracy entails uncertainty—and that uncertainty demands a measure of humility from all participants in an election, winners and losers alike.

Now for a more sobering take: When all is said and done, it seems most likely that President Donald Trump will lose his bid for reelection—but he will still have received more votes than four years ago, despite a reckless and corrupt administration that has badly mismanaged a pandemic and seen a growing economy transform into a dire recession. For the United States’ friends overseas who have wondered over the last four years whether the 2016 election was fluke: It was not. It was a reflection of what was and is a divided country grappling with divided responses to its past and to the challenges of the 21st century.

The outcome of Tuesday’s election that will take longest for the United States’ partners overseas to process is the fact that Republican Sen. Mitch McConnell looks poised to retain control of the U.S. Senate. (While there are races left to be called, this is the most likely scenario for now.) Both domestically and internationally, the Joe Biden presidency that would have been possible if Democrats had won the Senate would have been very different than the one that he now looks likely to lead.

On a practical level, it will take longer to fill senior administration posts that require Senate confirmation. But, more significantly, the legislative agenda to lift the United States out of the current economic and public health crisis, strengthen its democracy, and tackle the existential challenge of climate change has become much, much more difficult to advance. On climate change in particular, the prospect of the kind of significant investment needed to transform the U.S. economy and meet emissions targets is greatly diminished. For U.S. allies and partners around the world, the United States will stop being an at times gratuitous antagonist, and the Biden-Kamala Harris administration will reinvigorate U.S. diplomacy, but Washington will remain a frustrating partner on important issues.

At a deeper level, the loss of innocence that happened in 2016 remains. Though the votes are still being counted, the 2020 election looks likely to produce a victory for Biden and Harris, but it is not the full moral victory that I and many other Democrats had hoped for. The task of making the case for democratic values, of demonstrating that democracies can deliver, and of pushing back against demagogues and authoritarians is not one that can be left to the United States alone. Democracies on other continents need to step up—for their own interests and for the cause of democracy itself.

About the Author

Senior Vice President for Policy Research, Director, Europe Program

Dan Baer is senior vice president for policy research and director of the Europe Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Under President Obama, he was U.S. ambassador to the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) and he also served deputy assistant secretary of state for the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor.

- NATO’s Northeast Countries Have a Template for Europe’s New Security RealityCommentary

- “Supporting Armenia’s Democracy and Western Future”Testimony

Dan Baer

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Bombing Campaigns Do Not Bring About Democracy. Nor Does Regime Change Without a Plan.Commentary

Just look at Iraq in 1991.

Marwan Muasher

- Global Instability Makes Europe More Attractive, Not LessCommentary

Europe isn’t as weak in the new geopolitics of power as many would believe. But to leverage its assets and claim a sphere of influence, Brussels must stop undercutting itself.

Dimitar Bechev

- How Trump’s Wars Are Boosting Russian Oil ExportsCommentary

The interventions in Iran and Venezuela are in keeping with Trump’s strategy of containing China, but also strengthen Russia’s position.

Mikhail Korostikov

- Iran Is Pushing Its Neighbors Toward the United StatesCommentary

Tehran’s attacks are reshaping the security situation in the Middle East—and forcing the region’s clock to tick backward once again.

Amr Hamzawy

- The Gulf Monarchies Are Caught Between Iran’s Desperation and the U.S.’s RecklessnessCommentary

Only collective security can protect fragile economic models.

Andrew Leber