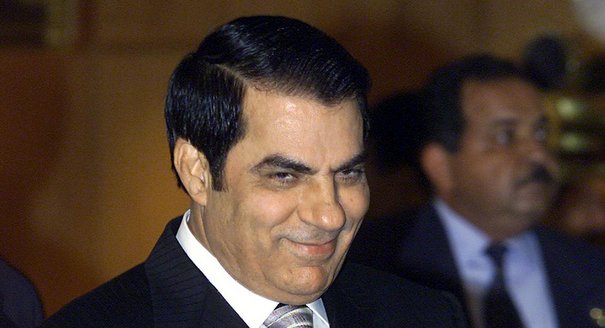

In the Tunisian presidential elections on October 25th, the reelection of President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali to a fifth term is not in doubt. Presidential and legislative elections held in 2009 in the Maghreb region have proved to be somewhat perfunctory, as nothing prevents the same ruling elite from getting reelected over and over--and no criticism is heard from the international community. Still, elections are a good opportunity to understand why the region is failing to democratize and what obstacles need to be removed to promote change.

In the case of Tunisia, the regime has managed to maintain good relations with its European and American partners because it maintains economic stability and security, thanks to open market policies and repression of Islamist movements. Furthermore, unlike its neighbor Libya, Tunisia does not formally reject Western democratic standards; it provides adequate education for its citizens and some protection of women’s rights. Those limited reforms have allowed the president to maintain an illusion of "change" while consolidating his control over the country. As a result, although opposition candidates are allowed to run in the presidential elections, Ben Ali is always reelected with record numbers of support, as in 2004 where he officially won 94.5 percent of the votes and in 1999 when he obtained 99.5 percent.

In order to appease domestic and international demands for free, fair and pluralistic elections, Ben Ali has tried to maintain a façade of pluralism while designing new laws to ensure contestants will not undermine his control. Those laws, pertaining to the simultaneous parliamentary and presidential elections, are generally enacted to weaken the president’s opponents and end as soon as he is reelected. Thus in 2002, the removal of presidential term limits in the constitution opened the way for Ben Ali to be reelected repeatedly—effectively to be president for life. In 2004, only candidates from parties that were already in parliament were allowed to run. Independent parties were required to collect the sponsorship of 30 deputies, which was impossible for them since they did not have any deputies in parliament.

Now, for the 2009 legislative elections, the domination of Ben Ali’s party, the Democratic Constitutional Rally (RCD), is even further reinforced by a new law. It states that 25 percent of parliamentary seats are automatically assigned to opposition parties. The other 75 percent of parliamentary seats are retained for the party that obtains the majority of votes, no matter what the actual vote count is. Under such a system, opposition parties cannot have a real impact in the parliament; only the RCD will be able to obtain a majority. Furthermore the 25 percent of deputies assigned to the opposition is split between "real" opposition parties and pro-Ben Ali parties that will support the RCD’s decisions. The RCD is also the only party whose electoral lists have been validated in all electoral districts. All the other parties complained of having their lists rejected without explanation, which has led to the withdrawal of the opposition Progressive Democratic Party. Stating that the party had its lists rejected in 17 districts, i.e. 80 percent of all districts, its members are now calling for a boycott of the election.

The scenario is similar for the presidential elections of 2009. A new law stipulating that a presidential candidate must have been the leader of his party for at least two years has prevented Mustafa Ben Jaafar of the Democratic Forum for Labor and Freedoms, as well as Nejib Chebbi, head of the Progressive Democratic Party, from running, as both parties have had a recent change in leadership. As a result, the only genuine opposition party candidate participating in the presidential elections is Ahmed Brahim, head of the Movement for Renewal. But even this party has complained of authorities interfering in their campaign, hampering party meetings by pressuring hotels not to rent them space or closing down the party’s newspaper. The two other candidates who have been allowed to participate are Ahmed Inoubli, representing the Unionist Democratic Union, and Mohamed Bouchiha from the Party of Popular Unity, both of whom are pro-government “opposition” parties. These two candidates will not bring any significant change: both have stated that the purpose of their candidacies is only “to get people accustomed to pluralism” and both have called for the re-election of Ben Ali.

What is different about the 2009 elections as compared to those in 2004 is that Ben Ali has put stronger emphasis on the need for “transparent” elections and he has appointed a new National Observatory for Presidential and Legislative Elections committee. Intended to placate the Tunisian people and the international community after his rejection of foreign monitors, this structure still consists mainly of members of the RCD. Such state laws and institutions help Ben Ali both assuage demands for pluralism and democracy and extend his control. Handicapped by tailor-made laws at every election, opposition parties also face increasing condemnation from their youngest activists, either for taking part in a “waste of time” election instead of engaging in more radical methods or for not having been able to create a common front to oppose Ben Ali’s monopoly.

The majority of the Tunisian youth is not that critical, however, lacking the ability to consider any option other than the president they have known for 22 years. To target them in these current elections, Ben Ali has also lowered the voting age from 20 to 18. This decision added a million new voters, not a negligible number considering that the total Tunisian population is 9 million. The RCD is targeting these new voters, even using new social networking technologies such as Facebook.

Since the RCD holds itself above all parties, Tunisian presidential elections should not be understood as an open competition, but rather as a managed referendum for or against the president. That even RCD members are not very interested in the elections is demonstrated by the fact that real voter turnout in past elections has been estimated at only 20 percent (although official estimates always put turnout at 80 percent). Standing against the president is not easy, as the RCD dominates, regulates and controls large cross-sections of society, including the police who intimidate potential opponents and potential election boycotters. Government-controlled trade unions and 8,500 of the 9,300 registered civil society associations have already declared their support for Ben Ali. Newspapers are covering only Ben Ali’s political and campaign activities and ignoring other political actors. Public offices have had large posters of the president on display for several months. Even the Tunisian diaspora’s vote is tightly controlled. The RCD itself has 2.7 million members, in an electorate of 5 million Tunisians. With other political parties so marginalized, supporting the RCD and Ben Ali is a prerequisite for any access to state services and any kind of social mobility.

Favoring economic development over fundamental freedoms is really the key to Ben Ali’s rule. As an example, the national committee for Ben Ali’s electoral campaign consists of many businessmen who during the campaign have put the emphasis on the economic side of the president’s program, rather than any sensitive political issues.

The United States and EU should not allow the predictability of these elections to create a lack of interest in Tunisian politics. This country stands as a perfect example of the semi-authoritarian regimes that have consolidated in the Arab world. These regimes have internalized and stage-managed the slogans of reform and pluralism to their benefit. They represent a real challenge to the international community, and require a new set of democracy promotion tools. International actors should insist that ‘official’ pluralism is not enough. They should encourage the president to undertake reforms that are more in line with the need for real pluralism and reform. Civil society must be encouraged to take part in national and international public debates without fearing police reprisals and the RCD’s relationship with opposition parties should be based on negotiation and healthy competition rather than on allegiance and tests of loyalty. The fact that Ben Ali’s authority relies more on police power than on the military gives the international community a better chance to engage in a meaningful dialogue with the president over the future of reform and executive power in Tunisia, as opposed to other authoritarian Arab republics where the army plays a larger and more problematic role.

Unless he amends the constitution again, the 2009-2014 term could be the current president’s last, since the constitution still fixes the presidential age limit at 75 and Ben Ali is already 73. However, unlike in several other Arab republics, Ben Ali’s successor is not at all clear. There are already signs of succession-related tension between his wife, Leila Ben Ali, and his son-in-law, Sakhr Materi, a businessman of 28 years who has been recently elected to the central committee of the RCD. While the October 25 elections are a foregone conclusion, the international community should engage with President Ben Ali after the election to encourage and insist on serious progress toward real pluralism and more meaningful elections in this fifth term of his.