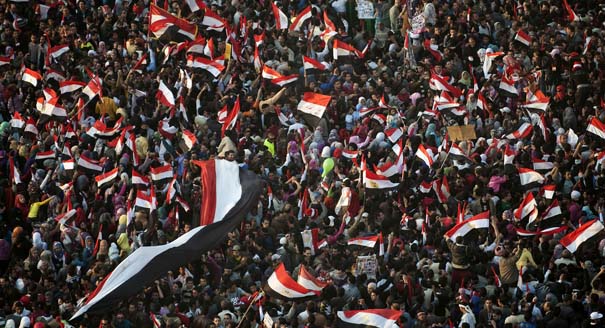

The “Arab Spring,” just like the Iranian Revolution of 1978-1979, occurred unexpectedly for both politicians and experts. While the reasons—corruption, the lengthy rule of the aged authoritarian leaders, an active youth, and modern technology of socialization—all seem obvious today, no one had foreseen what would happen.

Also, the astonishment of many analysts cannot be forgotten when they discovered the passivity of Islamists, who appeared secondary in the events. Europe and the United States, for a while, were hypnotized by the revolutionary wave, which was presumed to be a forerunner for democratization and other positive changes. Disappointment set in when the results of the revolution became evident: the gains were used by the forces that could be identified as Islamists. The victory of al-Nahda in the Tunisian parliamentary elections, the appeals for sharia law in Libya, the anticipated success of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egyptian elections, and the success of Islamists in Yemen seem to have changed popular opinion about the prospects of the end of political Islam and the hopelessness of Islamic fundamentalism.

In light of this, the question remains of what will come next. And there, I allow my imagination to run wild. The unanticipated spring and summer events in the Muslim world justify the most risky of the scenarios.

First, the revolutions will continue. The most difficult situation is in Syria. President Bashar Assad has been rejected by even the Arab world. Most consider him doomed and his exit to be only a matter of time, and that to happen very soon. Who will replace Assad is generally not a matter of much consideration but that needs to be given much thought. Shocks also await Yemen, which de facto already does not exist as a unified state. In mid-November there was unrest in Kuwait, the second case of disturbances in the Persian Gulf states—the first had been in Bahrain.

In this regard, it is impossible not to dwell on the fate of the Saudi monarchy as an internal cataclysm would mean a definite destabilization in the Arab and larger Muslim worlds. Herein lies the key issue: how to prevent a Saudi revolution from occurring. And besides that, one ought not to forget about Iraq.

Secondly, it is unlikely that a prompt onset of stability and conciliation will occur in countries where revolutions, saddled with Islamists, have already been victorious. The new authorities, whether an Islamic or a coalition government, cannot quickly resolve the economic and social challenges, especially of the youth population, while expectations in the society are high and success of the newly installed rulers, even if in appearance only, is needed without delay.

In addition to professionalism and capacity, this requires money. Inside the Arab countries under discussion there is not so much of it, and Europe and the United States do not have enough money even to resolve their own problems. There remain oil-rich brothers in faith. Even if they will finance Islamic revolutionaries (and it remains a question if they will), they will only do it on certain conditions.

If the new authorities do not demonstrate professionalism and an ability to garner outside help, disappointment is inevitable. But, if instead of addressing current problems, the new authorities begin to tighten political or political-religious control, disappointment will come even quicker. And that could usher in a second revolutionary sweep, or more precisely a counterrevolutionary wave. (It will be interesting to see the division of power in Egypt between the Muslim Brotherhood and the generals. What will they do if they can not peacefully divide it?)

Third, the rush of the second wave, as just noted, will be determined by the success of the new powers. At the same time, those new powers are associated with Islamists and the long-awaited return to “true religious values.” In the case of failure, there will be disappointment not only with Islamists’ practice, but with their ideology as well.

That, in turn, could lead to new tensions: a) between supporters of secular government and clericals, and b) inside Islamists groups. The latter possibility is of particular importance as it could lead to a rise of a radical wing of Islamists, who would explain the reasons for failure as the insufficient Islamization of government and society, and promote extreme positions. This could lead to another, possible third revolutionary wave.

A fourth outcome of the “Arab Spring,” which has turned into the “Islamic Fall,” could be the formation of an international bloc of radicals, comprising an Islamic Egypt, Syria, and Palestine, and possibly others. Such a bloc could become a real political force. Also possible would be the formation of an Iranian-led, radical, Shiite bloc, including Lebanon’s Hezbollah, Syria’s Alawites, and Shiites in Bahrain and Yemen.

And last, a kind of appendix, but also fascinating: in the spring of 2011, to the question of how the Arab Spring would influence Central Asia and Russia’s North Caucasus, I used to give a short answer, “In no way!” In the fall, after the Islamic Summer, I’ve changed my opinion and conclude it is rather possible that the Arab Spring could influence this region. Indeed, any Islamic political opponent could now point to their victory and recognition and question why in another country opposition has won, was recognized and why “we are worse than them?”

I am aware that this analysis oversimplifies some points and the nature of it is deliberately provocative. But, just as the events of 2011 in the Arab world had not been predicted, hypotheses of their future development could also seem quite unforeseen, and therefore robust projections, however unexpected, should provoke thought.