Marc Pierini

Source: Getty

The New French President's Foreign Policy

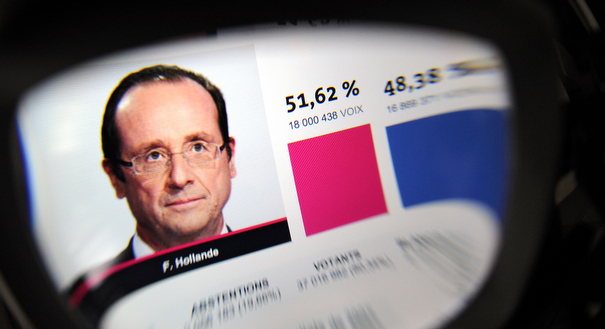

Now that François Hollande is the new president of France, the “campaign-to-power” is over. But the socialist candidate's campaign will now have to be reconciled with the power of the presidency.

Now that François Hollande is the new president of France, the “campaign-to-power” is over. But the socialist candidate’s campaign will now have to be reconciled with the power of the presidency. And foreign policy will factor strongly into this transition.

Barely three days after assuming office, the new president will attend the G8 summit at Camp David on May 18-19, followed by the NATO summit in Chicago. This will be shortly followed by the G20 summit in Mexico and a European Council meeting in Brussels in June. This summitry takes place against the background of the eurozone crisis, radical changes in many Arab countries, relentless massacres in Syria, a withdrawal from Afghanistan, and a stalemate on Iran’s nuclear program—to name just a few challenges.

In such a tight and momentous international agenda, the preparedness, style, and standing of the new French president will be under close scrutiny. This is especially true as he is a total newcomer and as he has campaigned on two platforms clearly at odds with some of his counterparts and both with international consequences: a faster than agreed withdrawal of French troops from Afghanistan and a renegotiation of the EU stability pact.

Europe and Globalization

One of the striking features of this presidential campaign was the broad distaste for European integration, the criticism of EU institutions, and the little that was understood about globalization. None of the candidates, and this includes Hollande, entertained the concept of France in a globalized world—a world where the center of gravity has moved to Asia and a world where a country like France cannot compete alone and must act within the EU framework.

The weakest spot in French politics is the remarkable inability of its politicians to explain why the country must act as a global economic power. All political parties blindly espoused the protectionist leanings of the citizens, although they know that such solutions do not make sense in today’s world. For example, one of the leading French brands with a global outreach, Renault, is regularly criticized for producing in Romania and Morocco (Dacia), and Turkey (Oyak Renault), although these are among its most profitable operations, helping the firm to remain a true global brand and a profitable one for the country.

The first item on Hollande’s agenda is indeed the euro crisis, and particularly France’s exposure to the debt crisis of some member states. The fact that France lags behind Germany in economic competiveness weighs heavily as well in the somber Europe-wide economic picture. But most measures apt to boost competitiveness in France run counter to the Socialist presidential program. Hard choices and straightforward pedagogy are ahead for the new president. How long can politicians mislead the public on such fundamental issues?

Turkey

Turkey is one the thorniest issues for the new French president, because the relationship between the two countries has been badly damaged by a series of skirmishes between Hollande’s predecessor, and the Turkish prime minister. France has lost billions of contracts as a result. What is urgently needed is a pacified relationship. One can be optimistic that Hollande’s polite approach will improve the atmospherics, but difficult substantive issues remain.

First, it is clear that France—and the EU—need Turkey as a booster to its competitiveness and as a fast-growing internal market. The recent acquisition by Aéroports de Paris (at a dear price) of 38 percent of the Turkish airport builder and manager TAV is a case in point: ADP declared to its shareholders that it was buying a double-digit growth firm, a rare example of a French firm acting globally.

Second, France and the EU need a politically stable, fully democratic, and economically dynamic Turkey, a Turkey at peace with itself internally and at peace with its neighbors, in particular Armenia and Cyprus. This can only be achieved through a functioning accession process of Turkey to the EU. This is not equivalent to saying that Turkey must enter the EU anytime soon, as many challenges remain to the accession process.

However, the accession process remains the best vehicle to modernize Turkey and, accession or not, this is in the EU’s and France’s utmost interest. Hollande will have to explain this to the French people. In the short term, he can start restoring France’s ties with Turkey by lifting the negotiation chapters blocked by his predecessor, without compromising the dual conditionality of the accession process.

The Arab World

The dramatic changes in the Arab world present another major foreign policy challenge for the new French president.

His predecessor entertained a privileged relationship with Tunisia’s Ben Ali, made Syria’s leader a special guest at a military parade, and unilaterally promoted Egypt’s Mubarak to the status of co-chair of the Union for the Mediterranean to the great dismay of other heads of state and government. All this finally crippled the Euro-Mediterranean Partnership by forcefully imposing the new mechanism of the Union for the Mediterranean.

The previous French policy in the Arab region has been shattered by the 2011 revolutions. Worse, Arab countries have been vexed by the xenophobic tones used by the right and the extreme right candidates during the campaign.

Hollande will now have to rebuild decent relations with largely unknown political partners—Islamists now dominate the political game in Egypt and Tunisia for example. He will also need to work with the Arab world more through the EU framework, rather than through a strictly bilateral one, which his predecessor preferred but did not work. A fresh start is needed.

The Road Ahead

Beyond these examples, many foreign policy challenges await Hollande as soon as he takes office on May 15. Yet, two of his strongest cards are the legitimacy deriving from his victory on Sunday and his calm, polite demeanor. In the summitry business, these are no small things.

As a by-product of the change at the Elysée Palace, another issue is on the table: how to rebuild confidence amongst France’s EU partners on both the EU issues in themselves and the key foreign policy issues briefly mentioned here.

Hollande should bear in mind that France’s partners in the European Council and the European Parliament were weary of his predecessor’s style, but they are also puzzled by the anti-Europe and France-centered wave that has characterized this presidential election.

A French president working positively and cooperatively is what the European Union urgently needs. France and the European Union will only surmount the momentous crises ahead of them, at home and abroad, if they play together.

Marc Pierini, a former EU career diplomat, has served as the EU Ambassador to Turkey, Tunisia, Libya, Syria, and Morocco.

About the Author

Senior Fellow, Carnegie Europe

Pierini is a senior fellow at Carnegie Europe, where his research focuses on developments in the Middle East and Turkey from a European perspective.

- The Iran War’s Dangerous Fallout for EuropeCommentary

- Unpacking Trump’s National Security StrategyOther

- +18

James M. Acton, Saskia Brechenmacher, Cecily Brewer, …

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Iran War Is Also Now a Semiconductor ProblemCommentary

The conflict is exposing the deep energy vulnerabilities of Korea’s chip industry.

Darcie Draudt-Véjares, Tim Sahay

- Taking the Pulse: Is France’s New Nuclear Doctrine Ambitious Enough?Commentary

French President Emmanuel Macron has unveiled his country’s new nuclear doctrine. Are the changes he has made enough to reassure France’s European partners in the current geopolitical context?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- The Iran War’s Dangerous Fallout for EuropeCommentary

The drone strike on the British air base in Akrotiri brings Europe’s proximity to the conflict in Iran into sharp relief. In the fog of war, old tensions in the Eastern Mediterranean risk being reignited, and regional stakeholders must avoid escalation.

Marc Pierini

- India’s Foreign Policy in the Age of PopulismPaper

Domestic mobilization, personalized leadership, and nationalism have reshaped India’s global behavior.

Sandra Destradi

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs