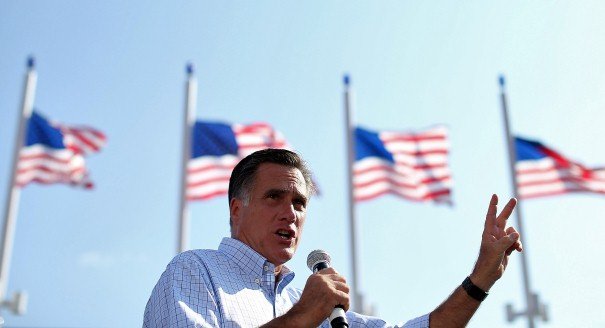

Foreign policy is not a major theme of the U.S. presidential campaign this year. However, the choice American people will make on November 6, will shape Washington’s foreign policy for the next four years and have an impact on the whole world. With Mitt Romney now nominated as the Republican Party candidate, the question is, if he were elected, what kind of foreign policy would the U.S. pursue under his leadership?

In his acceptance speech at the Tampa Bay convention on August 30, Romney didn’t address foreign policy. In the last few months, however, he has offered some remarks on international issues, and made a foreign trip that took him to Britain, Israel, and Poland. He has sounded staunchly pro-Israeli, very tough on Iran and Syria, and critical of China and Russia. The one remark in particular which is continues to ring in Russian ears is the one about Russia as America’s “number one geopolitical foe.”

Some top Russian America-watchers, including Sergey Rogov, have stated publicly that a Romney victory would be a disaster for U.S.-Russian relations. The people who would run Russia policy for Romney, Rogov argued, would put George W. Bush’s neocons to blush. Anyone reading John Bolton’s comments over the past few years can imagine what Rogov means if Bolton were to become Romney’s Secretary of State as some speculation has suggested. However, this is not a done deal, even if Romney were to win in November.Everything said on the campaign trail should usually be treated with a grain of salt, and with reason. For Romney, the principal battleground has been within his own party until now. He had to reach out to various Republican groups to get their support, including what the New York Times columnist Tom Friedman calls “the Dick Cheney wing” of the party. This can be seen to account for Romney’s vow to formally brand China a “currency manipulator” on the first day in office, and his referring to Russia as if it were still the Soviet Union.

If elected, Romney, like any chief executive in the United States, will have to reason and act differently, and probably “pivot to the center” as a result. Practical economic and financial considerations make full-scale confrontation with China extremely unlikely, and while Romney will probably not warm to President Putin, the importance of the Afghan transit across Russia will moderate his behavior vis-à-vis Moscow. There may be more rhetoric going the Moscow way, and symbolic actions of the kind exemplified by the Magnitsky Bill, going to become law next year. Relations may become frayed, but Russia will not be Romney’s priority—for good or for bad.

Crises between the U.S. and Russia could be products of the developments in the Middle East, in particular over Syria and Iran. The stakes are high for everyone, but highest for the countries in the region—and Washington. Russia, which is not a party to either the Syrian or the potential Iranian conflicts, and of course has its own broader interests to protect, needs to be extremely careful in how it reacts to possible U.S. and/or Israeli actions in the region.

One big issue in U.S.-Russian relations will be missile defense. Cooperation on the issue would transform the strategic relationship between the former Cold War adversaries, but a failure to agree would prolong the surviving adversity. Republicans have been traditionally more skeptical than the democrats on the possibility of a cooperative missile defense system in Europe. However, Steve Hadley, another individual now touted as a possible choice for the Secretary of State in a Romney administration, co-chaired a missile defense cooperation panel under the Commission for the Euro-Atlantic Security initiative (EASI). Hadley is a strong supporter and a vocal advocate of U.S./NATO-Russian cooperation in the area.

Russians are right to watch the U.S. election closely, and compare where the candidates stand on various world issues, including relations with Russia. However, Moscow needs to develop its own long-term strategy toward America, which would take into account U.S. parties, personalities, and policies, but would not be led by them. The original “reset” was made in the United States—that is why it was so poorly translated into Russian. Russia’s future U.S . policy needs to be pro-active, not reactive.