2011 brought new hopes for improving the situation in Dagestan, the largest of the North Caucasus Russian republics. These hopes were dashed in 2012 as the security situation has again deteriorated and become critical. According to the republic’s President Magomedsalam Magomedov, there have been 225 officially recorded crimes of a terrorist nature in Dagestan in the first nine months of this year alone. This number constitutes approximately three quarters of all terrorist attacks carried out in the North Caucasus.

Law enforcement officials have become the militants’ main target. Both local and federal politicians, as well as the media, consider the attackers to be little more than bandits. If this description is accepted as completely accurate, it means that the North Caucasus—Dagestan specifically—is an incredibly lawless territory.

At the same time, the militants are also being described as “illegal armed formations,” which acknowledges their substantial numbers, serious professional training, and the impressive cache of weapons that they have amassed. These characteristics distinguish these militants from ordinary criminals. From this vantage point, they look more like an extremely radical opposition faction that has been fighting the regime for the past fifteen years. “They are being killed, but new members join their ranks,” says Alexander Khloponin, the presidential plenipotentiary envoy in the North Caucasus Federal District. He notes that the average age of a militant is just 18.This fall, for the first time in six years, the federal authorities used army units in their struggle against the militants in the North Caucasus. The Ministry of Internal Affairs uses internal troops to establish new checkpoints in Dagestan; resources for seventeen checkpoints will be transferred there from Chechnya. On top of these federal efforts, the local government is planning the creation of “popular militias,” essentially calling for large-scale popular participation in the struggle against the militants. This, however, risks escalating the latent civil war which has been plaguing the republic for over a decade. “This place is like a volcano that is about to erupt,” Dagestanis warn.

Radical Islam is the foundation of oppositionists’ ideology and their stated strategic goal is to create some kind of Islamic quasi-state. This does not seem likely in the foreseeable future, given that separatism is not very popular in the North Caucasus. Nevertheless, the Islamic opposition, whose members are referred to as Wahhabis or Salafis, has some popular support, because they appeal to a number of grievances prevalent in the North Caucasus in general and Dagestan in particular.

People in the region are unhappy about a number of serious issues, including their current economic situation, growing economic inequality, corruption, high unemployment, and quality of education and medical care. According to the Levada Center polls, Dagestanis display the least confidence in their future—only 38.2 percent have hope that the situation will change for the better, compared to a regional average for the North Caucasus region of 45.5 percent. The conditions for religious radicalism are ripe when despair takes over, and calls for social justice based on strict Islamic principles and for alternative social structure may hold more appeal.

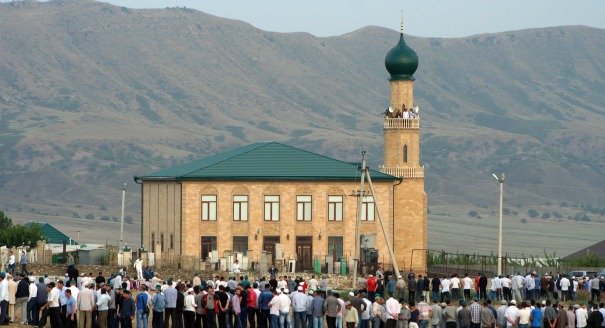

As a result, Dagestan has seen a politicization of Islam. It has spread beyond the Salafi radicals to include traditional Sufi Islam (in Dagestan, there are two largest Sufi orders, or tariqas—Naqshbandiya and Shaziliya). The radicals and the traditionalists loyal to the authorities are engaged in an intense struggle over their social influence and control of mosques, where social life is centered. This struggle is taking extreme and violent forms. One of the most influential Sufi sheikhs, Sirajuddin Israfilov, was assassinated in 2011, and Dagestan’s most prominent Sufi spiritual leader Said Afandi al-Chirkawi, who headed the Naqshbandi and Shazuli tariqas, was killed earlier this year.

Despite all of their internal conflicts, both radicals and traditionalists essentially share a common strategic goal, which is to Islamize Dagestan and institute a state guided by sharia law. The Salafi radicals believe that this can only be accomplished by seceding from Russia and establishing an independent state, while the traditionalists believe that the creation of the “Islamic space” is quite possible within the borders of the Russian Federation. In other words, they disagree on the path which will lead to the formation of the “Islamic territory.”

Dagestani society is moving toward greater reliance on traditional norms—both Islamic and ethnocultural. Civil identity is being replaced by a religious one: a sense of belonging to the Islamic ummah is becoming more important for a Dagestani than being a citizen of the Russian Federation. As Russian national identity is being increasingly defined in terms of affiliation with Russian Orthodoxy, federal control over the region is becoming even weaker and federal authorities appear unable to turn this tide.