- +1

Toby Dalton, Mark Hibbs, Nicole Grajewski, …

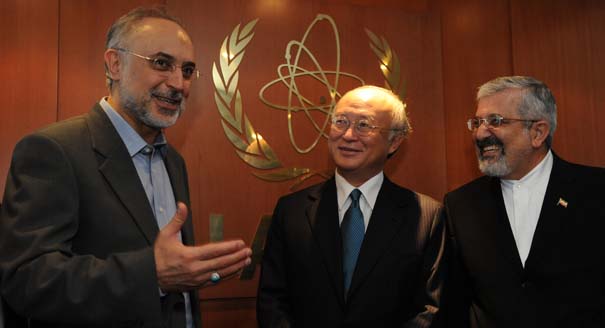

Source: Getty

The IAEA and Iran’s Face-Saving Solution

If the IAEA doesn't ask Iran tough questions, it may be easier to end the Iranian nuclear crisis. But would that stop Iran from secretly developing nuclear weapons?

Senior officials from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) will meet with Iranian counterparts in Tehran on December 13. The IAEA is prepared to visit a building located at Parchin, a site that Iran says is a conventional military facility but where the IAEA believes Tehran may have carried out tests related to the development of nuclear arms.

If the IAEA does not ask questions about what happened at Parchin and some other sites where it believes Iran carried out nuclear-weapons-related work in the past, it will be easier for Iran to cut a deal with the United States and other powers to end the Iranian nuclear crisis. But such an agreement with the five permanent members of the UN Security Council and Germany (P5+1) will be less effective in detecting whether Iran in the future is secretly developing nuclear arms.

For nine months, Iran has repeatedly denied the IAEA access to the location at Parchin, and the IAEA’s director general, Yukiya Amano, knows that this trip to Tehran may be in vain. It is highly unlikely that Iran will agree to a visit this week. It is possible that Tehran will only cooperate with the IAEA after it has scrubbed Parchin clean or perhaps once it has secured a face-saving agreement with the P5+1 about a political resolution of the Iranian nuclear crisis.Tehran may be particularly reluctant to provide access to the site right now because, after the U.S. presidential election, there is a greater chance that it will soon be offered an agreement. In fact, U.S. administration officials say that there is now a “window of opportunity” to make a deal, including one on the basis of direct U.S.-Iran talks.

In the meantime, however, the United States remains firm, warning that a continued lack of cooperation by Iran might result in more Security Council attention to the issue after the IAEA meets in March. Amano, likewise, wants to continue pressing Tehran to answer questions about Parchin and other sites where the IAEA’s information alleges there may be a “possible military dimension” to Iran’s nuclear program.

Since 2003 there have been two tracks in place on Iran—an IAEA track and a big-power diplomacy track. The IAEA track has been highly successful on the ground. Scientists and technicians are keeping tabs on Iran’s known facilities that can be used to generate plutonium and enrich uranium. They are making sure that Iran will be caught if it tries to “break out” and divert the uranium it is enriching for a nuclear explosive device. They are looking for evidence that Iran is carrying out any undeclared nuclear activities.

In parallel, the second, diplomatic track was opened up by the European Union. Three years later the circle was enlarged to include the Security Council—especially the EU’s two permanent members, France and the United Kingdom—plus the United States, Russia, and China.

The two tracks are separate, because the roles of the IAEA and the P5+1 are not the same. In recognition of this division of labor, when Amano was chosen by the board to succeed Mohamed ElBaradei as head of the IAEA in 2009, he indicated that he would leave high-stakes diplomacy and politics up to the IAEA’s policymaking organs—primarily the Board of Governors with its 35 members, which includes most countries with substantial nuclear activities—and instead concentrate on the agency’s more technical mandate serving 158 member states.

Negotiating a deal with Iran to resolve the nuclear crisis is in the hands of the P5+1. In 2013 they might find success, but only if Iran’s supreme leader and others he listens to overcome their deep distrust of the power of the permanent members—particularly the United States—to veto efforts in the Security Council. A deal will be all the more likely if the United States demonstrates leadership in making an offer that permits Iran to climb down from its open-ended nuclear ambitions.

Amano said last week that, in parallel with ongoing P5+1 diplomacy, the IAEA will continue asking Iran questions about the possible military dimension of its nuclear program. Some observers suggest that if diplomacy makes progress, however, the powers negotiating with Iran might urge Amano to exercise restraint and perhaps even to back off from pressing Iran to explain certain past activities.

That might make it easier to negotiate what Iran’s ambassador to the IAEA, Ali Asghar Soltanieh, in the agency’s boardroom last month called a “face-saving solution and a breakthrough from the existing stalemate” that Iran is “well-prepared” to accept. A solution proposed by the P5+1 along these lines might assure Iran that the investigation of its nuclear history will be handled in a way that does not disclose embarrassing information—and may not answer all the IAEA’s questions. For its part, Iran would have to bring into force and allow the IAEA to implement the Additional Protocol, and agree not to engage in the future in specific redline activities related to nuclear weapons development.

Such an approach might make it easier for Iran to save face, but it would be very difficult to accomplish. It might be perilous, for example, to draw a clear line between past activities that Iran would not have to completely explain, more recent and current activities that Iran must fully divulge to the IAEA, and activities that in the future would be prohibited. That would especially be the case if Iran were continuing its nuclear-weapons-related research, as some Western IAEA board member countries believe. Last month, a document of uncertain authenticity alleging that Iran has continued nuclear-weapons-related work until recently was leaked to the press, perhaps by parties who believe that such work by Iran is still ongoing.

Whatever the P5+1 does, it must protect the IAEA’s verification mandate. Since 2006 the Security Council has expressly asked the IAEA to investigate the allegations that Iran’s nuclear program possibly has a military dimension. If in a future agreement with Iran the P5+1 wants the IAEA to circumscribe or limit its investigation of Iran’s past activities, this would have to be done in a way that would not curtail the IAEA’s legal authority. Likewise, efforts to put into effect a ban on certain nuclear-related activities by Iran cannot distract or detract from the IAEA’s essential verification role in that country.

Ultimately, a P-5+1 agreement with Iran, in the light of Iran’s legacy of failure to disclose nuclear activities, should require the IAEA to express confidence through implementation of the Additional Protocol that all of Iran’s nuclear activities are dedicated to peaceful use. It is not clear how the IAEA could fulfill that task if it doesn’t have answers to all the questions based on the sum total of its evidence.

The IAEA has been openly pursuing the weapons allegations against Iran since last November. Then, Amano took a calculated risk and provided the IAEA’s evidence of Iranian nuclear-weapons-related activities to the Board of Governors, assuring that these allegations would become public. Amano was strongly encouraged to do this by the United States and other Western countries on the board. Russia however objected that doing so would escalate pressure on Iran to acknowledge past activities that in the future would not be permitted and hence make it more difficult to negotiate a diplomatic solution to the crisis.

Amano acted out of his conviction that his evidence concerning secret, highly sensitive nuclear-weapons-related activities should be formally reported to board members. He did that informed by the view that the IAEA must fulfill is its own mandate, not that of the P5+1. But Russia’s diplomatic assessment might ultimately prove correct.

About the Author

Nonresident Senior Fellow, Nuclear Policy Program

Hibbs is a Germany-based nonresident senior fellow in Carnegie’s Nuclear Policy Program. His areas of expertise are nuclear verification and safeguards, multilateral nuclear trade policy, international nuclear cooperation, and nonproliferation arrangements.

- Dimming Prospects for U.S.-Russia Nonproliferation CooperationArticle

- What Comes After Russia’s Attack on a Ukrainian Nuclear Power Station?Commentary

Mark Hibbs

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- The Unintended Consequences of German DeterrenceResearch

Germany's sometimes ambiguous nuclear policy advocates nuclear weapons for deterrence purposes but at the same time adheres to non-proliferation. This dichotomy can turn into a formidable dilemma and increase proliferation pressures in Berlin once no nuclear protector is around anymore, a scenario that has become more realistic in recent years.

Ulrich Kühn

- The U.S. Risks Much, but Gains Little, with IranCommentary

In an interview, Hassan Mneimneh discusses the ongoing conflict and the myriad miscalculations characterizing it.

Michael Young

- When Do Mass Protests Topple Autocrats?Commentary

The recent record of citizen uprisings in autocracies spells caution for the hope that a new wave of Iranian protests may break the regime’s hold on power.

Thomas Carothers, McKenzie Carrier

- The Greatest Dangers May Lie AheadCommentary

In an interview, Nicole Grajewski discusses the military dimension of the U.S. and Israeli attacks on Iran.

Michael Young

- The EU Needs a Third Way in IranCommentary

European reactions to the war in Iran have lost sight of wider political dynamics. The EU must position itself for the next phase of the crisis without giving up on its principles.

Richard Youngs