It’s dangerous to dismiss Washington’s shambolic diplomacy out of hand.

Eric Ciaramella

Source: Getty

In the eyes of the West, Ankara fluctuates on international issues and displays a lack of consistency in dealing with its allies. Why is Turkey’s foreign policy so erratic?

It has become an understatement in Western diplomatic circles to say that Turkey’s foreign policy is becoming more difficult to understand. In the eyes of Turkey’s Western partners, Ankara frequently fluctuates on international issues, displays a distinct lack of consistency in dealing with its friends and allies, and occasionally gives off the scent of an imperial attitude. These troublesome characteristics have become the hallmarks of Turkey’s diplomatic initiatives and statements, making it difficult—and at times perplexing—to make sense of Ankara’s foreign policy aims.

Yet Washington, Berlin, and Brussels see Turkey as a member of NATO and the Council of Europe as well as a candidate for EU accession and expect Ankara to display a pattern of behavior compatible with these affiliations. So why is Turkey’s foreign policy so erratic? And how should the West react?

While there are many reasons for the inconsistencies in Turkey’s foreign policy, there are also clear realities that will guide the country’s international direction in the years ahead. It is undoubtedly in Ankara’s best interest to be more consistent and strategic in future dealings with its international partners. But regardless of whether Turkey adopts a more stable foreign policy, the West—and particularly the EU—should keep Turkey close and continue to directly and actively engage top Turkish leaders.Turkey’s approaches to important regional and global issues have been marked by sudden policy reversals. In 2010, Turkey started befriending Syria by conducting multiple top-level visits, eliminating entry visas between the two countries, and improving business ties. It did so in the name of an (illusory, many said) ambition to elicit economic and social reforms in Damascus, although seasoned observers and a few courageous Turkish diplomats cautioned that the odds of succeeding in this aim were slim. When Turkey’s plan (predictably, the same would say) failed—and when Damascus unleashed a brutal repression against Syrian civilians—Ankara swiftly moved to ask for Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s removal.

Turkey’s initial rapprochement was perceived in Damascus as somewhat invasive, not to mention condescending, and its subsequent about-face was of course vilified by the Assad regime. When Ankara later decided to give support, whether direct or indirect, to jihadists heading to Syria through Turkey, neither the medium-term consequences on the balance of power in Syria nor the perceptions in Washington or Moscow were seemingly taken into account. By now, Turkey seems to have belatedly put in place a somewhat more stringent policy on controlling jihadists.

A similar reversal seems to have occurred in the rhetoric concerning Turkey’s relations with the European Union. Ankara has regularly presented its ties to Europe as a constant, central fixture of Turkey’s foreign policy. But after Turkey received international—and especially European—criticism for violently cracking down on protesters in Istanbul’s Gezi Park last June, the tone adopted by most government members was harshly anti-EU. The prime minister denounced a European Parliament resolution criticizing the Turkish response, and another Turkish minister issued a scathing attack on German Chancellor Angela Merkel, both of which are remembered vividly across Europe and beyond.

When the extent of the diplomatic fiasco surrounding Turkey’s handling of the Gezi protests became apparent, Ankara made a decision to tone down the language about the EU. On September 30, Turkey announced a “democratic package” detailing a range of reforms that was conveniently “inspired by EU principles.” And on November 5, the opening of a new chapter in the EU accession negotiations was the subject of eulogistic governmental statements in Ankara.

Such dramatic shifts do more than render Turkey’s foreign policy difficult to read and predict—they also dent Ankara’s credibility to an unprecedented degree.

The erratic nature of Turkey’s foreign policy also frequently obscures its aims on the global stage. Over the past few years, Ankara has shown signs of rethinking its traditional alliances and potentially forming new international relationships, often upsetting its longtime friends in the process.

If there is an aspect of Turkey’s foreign policy that has received praise from most of its neighbors and from non-EU Western countries, it is the fact that since 2005 Ankara has been pursuing EU accession negotiations. As a result, Turkey has conducted EU-inspired reforms in the economic and technical fields and, most importantly, in the domain of the rule of law. This is not to say that in Cairo, Rabat, or Washington, DC, there is a naive expectation that Turkey will in short order enter the European Union. But there is genuine praise for taking the risk. Similarly, business circles around the world see this accession process as a reason to invest in Turkey.

Yet, a peculiar Turkish mix of deep pride and strong language has often resulted in harsh anti-EU statements, usually written off as “meant for the national audience”—as if, in this day and age, there were a “national” and a “foreign” audience for political statements. The result is, again, perplexed international policymakers and diplomats who are unsure of Ankara’s real relationship to Brussels.

This sort of ambiguity also exists with regard to Turkey’s dealings on security, an area in which the issue of consistency has recently reached new lows. Turkey, when attacked by Syrian artillery fire in August 2012, rushed to NATO and asked for antimissile protection. NATO granted the request, and Patriot missile batteries have been deployed since January 2013. The deployment has recently been renewed for the year 2014.

However, when working on setting up its own missile defense system, the Turkish government announced off-the-cuff that it was likely to choose a Chinese system. While Ankara’s choice is an eminently sovereign one, this announcement represents a double blow for Turkey’s NATO allies. It means that, if the Chinese deal is confirmed, Turkey would operate a “stand-alone” missile system that would never be interoperable with NATO’s collective missile defenses. It also means that Turkey would fail to contribute to the upgrading of NATO’s collective defense, a key commitment of the 2012 NATO summit in Chicago and hence a Turkish commitment as well. Purchasing the Chinese system would in fact represent a negative contribution. Ankara’s meager explanations that it was swayed by Chinese promises of technology transfers (on an outdated weapon system) will not offset the political earthquake triggered by Turkey’s announcement anytime soon.

In addition, Turkey has perplexed its NATO allies and friends in the EU by seemingly pursuing new international affiliations. In 2013, it twice made public appeals to Russia and China to be accepted as a full member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). These appeals were essentially gestures of defiance vis-à-vis the European Union. The SCO does not seem to have answered Turkey’s request, which is not surprising considering the anti-Islamist stance of the SCO members and the image of Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) as rooted historically in Islamism. SCO members have also committed to fight separatism, and they were likely displeased with Turkish visits to the separatist Uighurs in China (Uighurs are also present in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan, all members of the SCO). But whether the SCO accepts Ankara or not, the fact remains that Turkey—a NATO member and a partner in its missile defense shield—asked to join an organization dominated by the two non-Western permanent members of the UN Security Council.

Ankara’s ambitious policy toward the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) in Iraq also raises serious concerns in Baghdad, once considered a Turkish ally, and Washington. Turkey hosted KRG President Massoud Barzani in a spectacular visit to Diyarbakır in November, and Ankara is working on a plan to directly import oil from the Kurdish region of Iraq (although this has not yet been approved by the Iraqi central government). The fact that Turkey’s policy de facto promotes the economic and financial independence of the KRG does not bode well for harmonious relations between Turkey and Iraq.

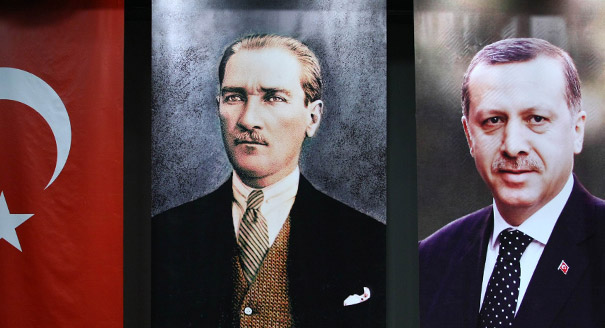

In Ankara, the AKP government has never liked scholarly comparisons of Turkey’s foreign policy to a “neo-Ottoman” strategy. Yet, in foreign policy, perceptions matter as much as principles, and Ankara has given the distinct impression that Turkey’s imperial history inspires its current international ambitions. This, in turn, often implies a departure from policy choices made since the proclamation of the republic in 1923.

When setting Turkey’s geographical priorities in May 2009, Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu referred first to the geography of the Ottoman Empire. During his tenure, he has defined Turkey as the agenda setter of the Middle East and the country “right at the center of everything.” These references, and the unexpected announcement in September 2011 of the creation of an Ankara-Cairo “axis of democracy” left regional and international countries deeply perplexed about Turkey’s international aims.

Seen from Cairo or Tunis, Foreign Minister Davutoğlu’s words have often been reminiscent of the Ottomans’ imperial grandeur, and his habit of constantly referencing cultural and religious affinities between Ankara and the Arab world has not necessarily been welcome. Arab countries do not instinctively perceive Turkey as one of them but see it first of all as a member of the Atlantic alliance that participated, albeit not in a combat posture, in NATO’s campaign in Libya.

The shifts in Turkey’s foreign policy seem so incomprehensible that Western observers have started asking questions and doing research on the topic. In late September, during his visit to New York for the UN General Assembly, Turkish President Abdullah Gül was besieged by questions about where Turkey was heading to an extent that no one in his entourage had predicted. And a scathing report was issued in October by the Bipartisan Policy Center in Washington that evaluated the current “turbulence” in the Washington-Ankara relationship. It was signed by two former U.S. ambassadors to Turkey.

Observers have listed multiple reasons for Turkey’s perplexing foreign policy. Undoubtedly, from the Southern Caucasus to the Nile River, Turkey is surrounded by an area rife with frozen conflicts, tensions, and active crises. In this volatile environment, the AKP government’s brand of foreign policy, loaded as it is with considerations such as religious affinities, may have overestimated the goodwill Ankara would get from its Arab neighbors. Turkey’s genuine and unprecedented economic success (often portrayed by the government as even more impressive than it really is) may also have induced overconfidence.

In addition, the “strategic depth” concept that forms the base of Turkey’s foreign policy may have misled the Turkish government in more than one way. This concept is based on the idea that Turkey’s history and geographic position afford it advantages that it should use to become an influential power in several regions. Although seemingly discursive from a purely narrative point of view—history and geography may indeed be seen as assets for Turkey’s foreign policy—this concept tends to minimize, or even obliterate, other core factors, such as the colonial perceptions associated with the Ottoman Empire, the fact that Turkey’s NATO membership makes it a distinctly Western actor on the international stage, the strong Russian influence in the South Caucasus and Syria, and Turkey’s energy dependence.

Another explanation focuses on ballot box considerations. It posits that the AKP, which has gradually lost its urban liberal followers, is trying to recoup that loss by playing on conservative religious feelings or nationalist leanings among its core electorate. This theory explains Ankara’s fierce defense of deposed Islamist president Mohamed Morsi in Egypt as an appeal to Turkish Muslims and its stance on Chinese missiles as proof that Turkey will not accept being technologically dependent on the West.

Differences in political culture also matter. What is routinely perceived within Turkey as arm-twisting in defense of national interests often appears as mere chest beating abroad. Similarly, the volatile nature of Turkish domestic politics tends to reflect badly on its foreign policy, a realm where strategic planning should be more influential than short-term ballot box tactics.

Regardless of the reasons for inconsistency in Ankara’s foreign relations, there are a number of hard facts that will shape Turkey’s future and therefore should influence its foreign policy.

During the past eleven years, Turkey has grown fast, reformed deeply, and witnessed a political revolution of sorts as the religious conservatives have taken center stage. The society has modernized even faster than Turkish political personnel, and Ankara’s diplomacy has become immensely more visible and active.

Yet the region around Turkey has now entered an era of unprecedented political and security instability, economic troubles, and human tragedies. Cards are being reshuffled and roles are changing: The United States and the European Union may seem less influential to some, while others may see Russia and Iran as having scored points. Qatar has recently gone quieter. Turkey has been spectacularly active during the past four years but has gained little additional influence, to put it mildly.

In the future, Turkey’s foreign policy will have to face a number of deep-seated realities. In defense terms, Ankara is heavily dependent on NATO and formally committed to its policies, including by hosting an early-warning radar station for its missile defense shield. It does not have the luxury to run away from this affiliation, nor does it have an interest in doing so.

In economic terms, Turkey is strongly anchored to the European Union, and to a lesser extent to the United States, through trade, investment, and technology transfers. Agreements such as the EU-Turkey customs union have played a key role in lifting Turkey’s industry to Western standards over the past sixteen years. The ongoing EU accession negotiations also help bring foreign direct investment as well as short-term money to Turkey.

In the short to medium term, Turkey will be confronted with a number of strategic challenges, most of them invisible in the media. First among these is the country’s current, abrupt decline in fertility rates, which will result in the population leveling off within ten to twenty years at around 85 to 92 million inhabitants. This will have immense consequences for Turkey’s labor-intensive export industry, which is primarily focused on automotive goods and domestic appliances, and for its welfare and education systems.

The inadequacy of Turkey’s research and development capabilities will also prove challenging. For a number of reasons, the country lags far behind India or Brazil, let alone China, in computer sciences, biotechnology, and space technologies. Ankara will have to think hard and smart about how to compensate for these fundamental shortcomings. If it needs more technology transfers, Turkey will have to decide whether these transfers will come more easily from Russia, China, or India, on the one hand, or from the European Union and the United States, on the other. If Turkey needs more engineers and technicians, it will have to decide whether to look to India or Brazil or to the Turkish-qualified labor force in Europe and the United States. It will need to address whether reverse immigration is a prospect or if Turkey will import manpower from less advanced countries. These momentous challenges will have direct foreign and economic policy implications.

In many ways, Turkey’s alliances, and therefore its foreign policy, will depend on the specific niche the country wants to occupy: Does it aim to be a mere energy hub linking the Caucasus, Iraq, or the Eastern Mediterranean to Europe? A builder of airports and social housing and an exporter of cookies and mattresses to the neighboring Middle East? An advanced technology center and maker of aircrafts and satellites? Such crucial choices call for a well-thought-out, multifaceted, and coherent strategy at home and on the international stage. These relevant factors have little to do with religious affinities, historical evocations, or sentimental proclamations.

In Turkey as everywhere, all politics are local. The determining factor for any political decision will undoubtedly be the electoral fever that will grip the country until the general elections in June 2015. EU and Western politicians should brace for impact. While formal statements and official visits will be carefully crafted to erase the embarrassment of the Gezi protests, ease up the EU accession process, and appease the West, words addressed to the Turkish voters may often run in the other direction.

This should not, however, dissuade Western leaders—and especially European leaders—from trying to steer relations with Turkey back onto a mutually beneficial path. To do so, European leaders should engage more closely and directly the Turkish top leadership. This renewed engagement should be based on four ingredients.

First, the EU should acknowledge that there is a fundamental imbalance in the EU-Turkey customs union because Turkey is obligated to unilaterally abide by the free-trade agreements passed by the EU. This should be corrected, and Turkey should adopt a positive approach to the customs union. Similarly, the European Union and the United States should pay greater attention to the impact that their proposed trade agreement, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, would have on Turkey.

Second, the EU should promptly proceed with the process of visa liberalization. It agreed to open dialogue on this process in exchange for Turkey’s signature on an EU-Turkey readmission agreement for illegal migrants, which should be swiftly implemented.

Third, Turkey’s accession negotiations to the EU should be given a political boost under a clear, mutually accepted dual conditionality: the negotiations’ own conditions (according to EU law and political criteria) and a ratification process, which will obviously include a popular referendum if a government so decides. Renewed impetus on the accession negotiations will also factor into Turkey’s course on fundamental liberties and tolerance within its own society.

Lastly, the EU should vastly increase programs aimed at youth, such as the Erasmus student exchange program, and civil society in order to support people-to-people rapprochement and foster liberal democracy and tolerance.

On Turkey’s side, after the haste and hubris that have often characterized its policy initiatives in recent years, the government should look at where exactly its strategic interest lies. The dream of again becoming the dominant power in the middle of all things is, by way of geography, history, and shifting equilibriums, a legitimate one for Turkey. But it should not come at the price of unpredictability and inconsistency. This is why Turkey’s partners, and not only its Western partners, are hoping for a more stable and reasoned course of action.

There are signs that Turkey may be considering such a pragmatic course. There is the fact that Ankara specified that the September 30 democratization package was “inspired” by EU principles, for example, and made references to tolerance and consultations in the society. Or that the Chinese missile deal is said to be only at a draft stage and the EU-Turkey readmission agreement will be signed on December 16. There are hopeful indications that Turkey may be willing to compromise on long-standing disputes, such as on the Cyprus issue and Armenia, and there has been a move toward more stringent controls on the flow of jihadists and arms into Syria. And against this encouraging backdrop, the Turkish prime minister is preparing to visit Brussels.

In the final analysis, Turkey faces an important test: Will all these promising developments lead to a lasting readjustment in Turkish foreign policy, or will they prove to be more fleeting words? And in terms of national politics, will Ankara move toward a tolerant brand of democracy, open to difference and dissent, or remain authoritarian? Its choices will shape both Turkey’s international image and its future performance.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

It’s dangerous to dismiss Washington’s shambolic diplomacy out of hand.

Eric Ciaramella

EU member states clash over how to boost the union’s competitiveness: Some want to favor European industries in public procurement, while others worry this could deter foreign investment. So, can the EU simultaneously attract global capital and reduce dependencies?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

Europe’s policy of subservience to the Trump administration has failed. For Washington to take the EU seriously, its leaders now need to combine engagement with robust pushback.

Stefan Lehne

Leaning into a multispeed Europe that includes the UK is the way Europeans don’t get relegated to suffering what they must, while the mighty United States and China do what they want.

Rym Momtaz

As Gaza peace negotiations take center stage, Washington should use the tools that have proven the most effective over the past decades of Middle East mediation.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes, Kathryn Selfe