Federica D’Alessandra

In Nyamagabe in southern Rwanda, flowers brought by residents attending the 28th local commemoration of the genocide against the Tutsi are seen on the ground at the Murambi genocide memorial. (Photo by SIMON WOHLFAHRT/AFP via Getty Images)

What the White House and Congress Can Do to Prevent Global Mass Atrocities

Lessons from the first Trump administration for today.

Summary

The Unites States has long recognized that preventing and responding to mass atrocities is both a moral responsibility and in its national security interest. Commitment to atrocity prevention and response has long enjoyed broad bipartisan support, and the U.S. government has long been a global leader on the issue. In 2011, the United States was the first country to establish an interagency body dedicated to atrocity prevention. Ever since, each Republican and Democratic administration—with the support of Congress—has taken additional, important steps toward implementing this objective.

In 2019, under President Donald Trump, the United States was the first country to enact federal legislation addressing global mass atrocities. The Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act mandates the White House to report annually to Congress on government-led atrocity prevention efforts. Under the act, the second Trump administration will again be required to report to Congress by mid-2025, raising the question: What is in store for the atrocity prevention agenda under Trump 2.0?

This paper reviews the atrocity prevention track record of the first Trump administration and other relevant action taken so far in this second term to parse out what efforts to sustain and uphold U.S. atrocity prevention obligations could look like under Trump’s second White House. This paper highlights how a number of steps the administration has already taken, including but not limited to the recently announced reorganization of the U.S. Department of State and the effective dissolution of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), unless promptly addressed, will raise dire challenges for the readiness and capacity of the State Department and other relevant agencies tasked with operationalizing U.S. commitments to this end. Accordingly, this paper advances a number of actionable recommendations that both the White House and the U.S. Congress should urgently consider to ensure the administration stands ready and capable to fulfill its obligations under the Elie Wiesel Act and other relevant legislation.

Introduction

In light of the second Trump administration’s overhaul of U.S. foreign policy, and the flurry of executive orders, reform, and reprioritization undertaken in its first three months, it seems reasonable to ask what the future might hold for historic U.S. commitments anchored in the protection of civilians, the promotion of human rights, global accountability, and the rule of law. Following the Holocaust, a deep-seated consensus—rooted in long-standing U.S. principles and values—has formed across both Democratic and Republican administrations that genocide and the deliberate targeting of civilians cannot be tolerated.

Beyond the humanitarian imperative to protect civilians in harm’s way, it has long also been recognized that mass atrocities can threaten international peace and security, including by fueling conflict, generating uncontrolled migration and refugee flows, and destabilizing entire regions. The United States’ own national security is affected when masses of civilians are slaughtered, refugees flow across borders, and apparent murderers wreak havoc on regional stability and livelihoods. When mass atrocities go unchecked, perpetrators are emboldened, “creating openings for violent extremism to flourish; creating grievances that extremists can exploit; disrupting economic relations and undermining progress on economic development; [and] contributing to state fragility.”

Undoubtedly, mass atrocities and genocide demand action. Yet, when governmental engagement arrives too late, crucial opportunities for prevention—or to mobilize through low-cost, low-risk action—are often missed: “By the time these issues have commanded the attention of senior policy makers, the menu of options has shrunk considerably and the costs of action have risen,” ultimately “necessitating costly ex post intervention.” This underscores the need for early and proactive engagement, including through interagency coordination, intelligence collection, and analysis to inform early warnings, monitoring, and documentation, and to ensure that all available options to prevent and respond to mass atrocities can be effectively leveraged in time.

After witnessing the devastating consequences of the failure to prevent genocide and other mass atrocities in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s, U.S. officials vowed to ensure that similar atrocities would never again go unchallenged. Thus, in 2007, a historic Genocide Prevention Task Force was convened (under the stewardship of former secretary of state Madeleine Albright and former secretary of defense William Cohen) to recommend what steps the U.S. government might take to this end. Receiving bipartisan praise, its work set in motion a process that would lead the Barack Obama White House to declare mass atrocity prevention a “core national security interest and a core moral responsibility” of the United States and to direct the coordination of a “whole-of-government approach” to deliver on this national security imperative.

Bipartisan consensus has since been firm in support of U.S. commitments and global leadership to prevent and respond to mass atrocity scenarios. In 2011, the United States was the first country to establish an interagency body dedicated to atrocity prevention; each of the following Republican and Democratic administrations took additional, important steps toward implementing this agenda. In 2019, the United States was the first country to also enact federal legislation addressing global mass atrocities. The Elie Wiesel Genocide and Atrocities Prevention Act, signed into law by Trump, mandated the White House to report annually to Congress on government-led atrocity prevention efforts. Indeed, through his first term, Trump and his administration took a number of additional steps aimed to further implement atrocity prevention objectives. This included enshrining a U.S. commitment to “hold perpetrators of genocide and mass atrocities accountable” made in the 2017 U.S. National Security Strategy, and taking action to implement U.S. commitments under the Elie Wiesel Act, including submitting the first two White House reports to Congress under Section 5 (in 2019 and 2020).

Trump also signed into law a number of other relevant statutes, such as the 2017 Women, Peace, and Security Act, the first comprehensive legislation on this topic in the world; the 2019 Global Fragility Act, which aims to improve the U.S. government’s approach to addressing global fragility and violent conflict by focusing on strengthening national and local governance, promoting conflict resolution, and preventing violent extremism; a number of thematic and country-specific legislation, including the 2018 Iraq and Syria Genocide Relief and Accountability Act authorizing U.S. government agencies to provide humanitarian, stabilization, and recovery assistance for nationals and residents of Iraq and Syria, in particular ethnic and minority individuals at risk of genocide and other atrocity crimes; and the 2019 Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act setting forth sanctions and financial restrictions on institutions and individuals related to mass atrocities in Syria. In 2019, the Trump administration also released the U.S. Strategy on Women, Peace, and Security to operationalize commitments under the relevant act. The Joe Biden administration further built on its predecessors’ contributions by publishing the first-ever national, government-wide U.S. Strategy to Anticipate, Prevent, and Respond to Atrocities (SAPRA) in 2022, which also remains in effect.

Under the Elie Wiesel Act, the second Trump administration will be required to report annually to Congress starting in mid-2025 on progress made toward its implementation (including on current initiatives, funding allocations, risk assessments, and training programs, among other issues),1 raising the question: What is in store for the atrocity prevention agenda under Trump 2.0? In its first three months, the Trump administration has already taken limited but important action in support of certain atrocity prevention objectives. This includes executing an arrest warrant against an alleged Rwanda genocidaire; sanctioning two individuals, including a Rwandan government minister, for their alleged support of M23; and sanctioning Houthi leaders (as well as their network and specific vessels) for unlawful weapons procurement and destabilizing violence in the region.

Although no one knows what additional steps, if any, the second Trump administration will take to uphold its responsibilities under the act, it might be instructive to look back at the first administration’s track record, and other relevant actions taken so far in this second term (including the recently announced dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), among other congressionally mandated entities, and the reorganization of the U.S. Department of State), to parse out what U.S. government efforts to sustain and uphold the atrocity prevention agenda could look like under Trump’s second White House. See box 1 for an overview of the U.S. government’s approach to atrocity prevention (up to the recent reorganization of the State Department, which foresees abolition of many bureaus holding key responsibilities for atrocity prevention), including a discussion of the task force, its composition and mandate, and other relevant federal agencies involved in supporting and operationalizing U.S. commitments under the act.2

Box 1: A Primer on the U.S. Government’s Recent Approach to Atrocity Prevention

The U.S. government approach to atrocity prevention, mitigation, and response has evolved significantly over the last fifteen years and draws from a number of statutes, authorities, and related strategies, alongside the U.S. Strategy to Anticipate, Prevent, and Respond to Atrocities and the Elie Wiesel Act. In addition to fulfilling its responsibilities under relevant legislation, each administration is also required to regularly integrate atrocity prevention efforts with thematic workstreams and priorities that align with its agenda. For example, the Joe Biden administration made food insecurity and starvation as a weapon of war key thematic priorities of its atrocity prevention work, while the first Donald Trump administration emphasized religious freedom and combating antisemitism.

It has long been understood that directing the implementation of atrocity prevention commitments requires interagency coordination and a whole-of-government approach. For this reason, the Barack Obama White House established an interagency committee previously known as the Atrocities Prevention Board, which became the Atrocity Early Warning Task Force under the first Trump administration. The task force is White House–led, but houses its secretariat with the State Department’s Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations and draws from the contributions of a number of other U.S. government departments and agencies, including: the Departments of Justice, Treasury, Defense, and Homeland Security; the intelligence community; USAID (per the Trump White House 2019 report) (until recently); as well as the National Security Council and the FBI (per its 2020 report). The task force’s responsibility is to enhance U.S. government efforts to “prevent, mitigate, and respond to atrocities” by: “monitor[ing] developments in atrocity risk globally to alert the interagency to early warning signs; improv[ing] interagency coordination . . . to address gaps and lessons-learned . . . ; and facilitating the development and implementation of policies” to further build U.S. government capacity to pursue atrocity prevention, mitigation, and response through a variety of “economic, financial, and prosecutorial tools” (discussed in this paper).

In addition, its mandate requires the task force to regularly consult and work with civil society, at home and abroad, both to assist its early warning efforts (by leveraging forecasting by initiatives such as the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and Dartmouth’s Early Warning Project to supplement the State Department’s Atrocity Early Warning Assessment, and the intelligence community’s confidential Annual Mass Atrocities Risk Assessment) and to help identify the appropriate strategies and partners on the ground, given its “greater access to local communities” in countries at risk. As part of its external engagement, the task force also regularly receives feedback and recommendations from civil society on how to improve its efforts and partners with a number of both governmental and nongovernmental institutes (including the State Department’s Foreign Service Institute, the U.S. Army Security Force Assistance & Stability Integration Directorate, and, until recently, the U.S. Institute of Peace, among others) to deliver trainings and raise awareness among civilian and military personnel of both the United States and partner countries.

Finally, the task force works through “multilateral and other diplomatic engagements,” both bilaterally and with groupings of “like-minded partners” (such as the International Atrocity Prevention Working Group) through “coordination and burden sharing” to “develop actionable programs,” “inform mitigation and accountability efforts,” and “implement capacity building programs . . . that help partner countries more effectively prevent and respond to atrocities.”

For the most up-to-date account of U.S. government efforts in all of these areas, including efforts by sector and how these translated to specific initiatives within at-risk-countries, see the 2024 Biden White House report.

A Review of Atrocity Prevention Under Trump 1.0

Despite the challenges already arising from the approach the second Trump administration has taken in its first few months to cut government spending, shrink the size of the federal government, and reorient U.S. foreign policy in accordance with the president’s America First agenda, the approach the administration might take toward long-standing U.S. commitments to atrocity prevention should not be a foregone conclusion. In fact, during his first term, Trump and his administration took a number of important steps to fulfill their obligations under the Elie Wiesel Act and other relevant legislation. Even though a track record is, of course, not always indicative of future performance, the most instructive starting point to assess what approach the second Trump administration could take on atrocity prevention issues might be to look back at what the president and his administration already achieved during his first term.

The last congressional report submitted by a Trump White House dates back to 2020 and is particularly instructive to appreciate how the administration might have understood its commitments, identified priorities, and implemented action pursuant to the Elie Wiesel Act and other relevant authorities.3 For example, per Section V of the report, in 2019 the administration abolished the high-level interagency working group previously known as the Atrocity Prevention Board, creating instead a White House–led Atrocity Early Warning Task Force, which continued to meet regularly at the working level throughout his term. Sections III and IV of the report emphasize how the administration “used multilateral and bilateral diplomatic engagements,” “worked with like-minded partners,” and “engaged with civil society” to “reaffirm the U.S. commitment to atrocity prevention, publicly denounce perpetrators, and raise the alarm” on countries where atrocities are ongoing or at risk. Given the “important focus” the human rights crisis in Xinjiang received from the administration, it is helpful to look at this particular case to better understand how the administration implemented this approach in practice.

To begin with, the administration leveraged a number of United Nations (UN) meetings, platforms, and other commemorations to “publicly condemn China’s ongoing and escalating abuses of the Uyghurs and other members of ethnic and religious minority groups in Xinjiang.” This included multiple initiatives:

- raising the issue at a number of UN Security Council meetings;

- convening high-level events during the seventy-fourth session of the UN General Assembly;

- signing an unprecedented joint statement with twenty-three nations “calling attention to the situation in Xinjiang and urging China to demonstrate respect for the rights of members of ethnic and religious minority groups”; and

- reinforcing “its high-level messaging on atrocities in Xinjiang” at other White House–led events where Uyghur survivors and their families gave “powerful testimonies of the Chinese Government’s escalating repression against members of religious groups in China.”4

The Department of State also held a number of consultations with civil society organizations, regularly communicated with Uyghur survivors and their family members, and leveraged honors (such as the 2020 International Women of Courage Award) to “bring international attention to the [Chinese Communist Party’s] campaign of repression.”5 Then secretary of state Mike Pompeo also issued a number of statements “about the harassment, imprisonment, or detention” experienced by Uyghur survivors, activists, and their families and strongly condemned the Chinese Communist Party’s “coercive population control practices, which include forced sterilization and involuntary birth control methods.” In 2021, Pompeo also issued a (somewhat controversial) official genocide determination against China, while the State Department pursued additional accountability and mitigation measures, such as financing efforts to gather evidence and hold perpetrators accountable. These measures included allocating “$1 million to address issues of repression in Xinjiang” in 2019 and working with other U.S. government departments, including the Treasury Department, to impose export controls, visa restrictions, and economic sanctions under the Global Magnitsky Act.6

Although the U.S. government’s prioritization of this particular situation was criticized by some for overshadowing other urgent human rights crises, the above highlights how—even as it criticized the UN and other international organizations and withdrew the United States from the UN Human Rights Council—the first Trump administration understood and embraced the crucial need to leverage international diplomatic forums (including the UN itself) and work with like-minded countries and partners in civil society to advance its objectives. Importantly, the administration also pursued accountability and mitigation efforts with respect to other crises beyond Xinjiang (most notably in Burma/Myanmar, Iraq, South Sudan, and Syria, among others), which are equally worth reviewing as they provide insight into additional action and areas of intervention not available or applicable to the situation in Xinjiang.

One such area is the pursuit of criminal accountability by means of cooperation, financial support, and technical assistance to international justice and law enforcement mechanisms such as the UN Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh/ISIL (UNITAD) and the UN International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism in Syria (IIIM). U.S. cooperation and assistance aimed to “develop actionable case files” against perpetrators of atrocities in Syria and Iraq,7 including by supporting initiatives aimed to gather battlefield evidence and sharing the State Department’s own documentation with prosecutors in Europe. In addition, the Trump administration reported collaborating with international judicial institutions “to strengthen justice and accountability mechanisms”8; “working through the [UN Security Council] to address abuses by armed groups and government forces” in Burundi, the Central African Republic, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo; and allocating “$10.5 million towards atrocity prevention programming globally” from USAID and the State Department’s 2019 budgets.9

Just as it supported global accountability efforts, the first Trump administration also leveraged domestic authorities (including under criminal and immigration statutes) and the capabilities of other U.S. government agencies, such as Homeland Security Investigations, the Human Rights Violators and War Crimes Center, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), to carry out multiple goals: ensuring the United States “does not become a safe-haven for perpetrators of atrocities,” deploying a “range of economic and financial pressure tools to disrupt and deter atrocities” and to respond to or contain military threats emerging from Syria and Islamic State–held territories in Northern Iraq, and undertaking “capacity-building programs for partner governments.” This reportedly led to in-depth assessments and training for local law enforcement to “stabilize border areas and inhibit illicit financial flows, collect evidence, and conduct witness interviews following suspected atrocities.”10 Finally, the administration reported delivering a number of atrocity prevention trainings—both in person and online, through USAID, the State and Defense Departments, and the FBI—for civilian, military, and law enforcement personnel from both the United States and partner countries.11

Although the civil society assessment that followed the 2020 White House report raised a number of areas for improvement and ongoing substantive, structural, and procedural concerns with the administration’s approach, it also credited the administration’s work as “valuable and constructive contributions to global efforts to mitigate, prevent, and respond to mass atrocities and genocide.” On this basis, then, the first Trump administration’s track record on atrocities prevention suggests there may be sustained progress during his second term. Yet, unless promptly addressed, a number of steps the second Trump administration has already taken will raise dire challenges for its ability to uphold atrocity prevention commitments, even if the political will is there to do so.

Atrocity Prevention Under Trump 2.0: What’s Most Immediately at Stake?

The most pressing issue, in light of the recently announced reorganization of the State Department, is that it remains unclear which part(s) of the federal government will be given the lead and/or corollary responsibilities to implement U.S. government atrocity preventioncommitments moving forward. This is because the restructuring, as currently envisioned, abolishes many offices and bureaus (which were formerly under the Undersecretary of State for Civilian Security, Democracy and Human Rights, another office being abolished) that have historically played a significant role in implementing U.S. government commitments in this area. These include: the Bureau of Conflict and Stabilization Operations (CSO), which has historically housed the task force’s secretariat, and directly supported the State Department’s Conflict Observatory; the Office of Global Criminal Justice (GCJ), which has been leading the implementation of U.S. policy on atrocity crimes accountability since it was created in 1997; the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement (INL), which has supported the investigation and prosecution of perpetrators by U.S. authorities and partner countries (including Ukraine); the Office of International Religious Freedom (IRF), which inter alia played a crucial role in supporting U.S. policy toward atrocities in Xinjiang during the first Trump term; and the Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (TIP), among others.

In addition, the Trump administration has announced drastic cuts to international organizations and other multilateral initiatives crucial to advancing atrocity prevention objectives within (and alongside) international partners, forums, and organizations. Moving forward, clarity on how any and all atrocity prevention responsibilities previously under the competences of each abolished entity will be reallocated is imperative, to avoid losing expertise, readiness, and capacity to the detriment of the U.S. government’s ability to deliver on its commitments.

Given the key role USAID played (according to the administration itself) in implementing U.S. government commitments and initiatives on atrocity prevention, its effective dissolution will prove to be a key obstacle to the capacity and, in all likelihood, effectiveness of efforts that might be pursued by the second Trump White House. The administration’s decision to overhaul the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP), a government-funded research institution, by firing most of its board, executive leadership, and employees and taking over its premises, is also likely to impede its pursuit of atrocity prevention efforts, given the instrumental role the institute has long played in generating groundbreaking research and analysis to support U.S. government efforts at the strategic, policy, and operational levels; supporting training; and convening policymakers.12 Indeed, USIP’s atrocity prevention contributions date back to the very origin of the agenda, when it partnered with the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum and the American Academy of Diplomacy to convene the earlier-mentioned Genocide Prevention Task Force.

To make up for the loss of contributions from these two hugely important institutions, the State Department and other government agencies will require a massive surge to supplement their own work and initiatives on atrocity prevention. This seems improbable, however, at least at present, given the reorganization under way and the huge cuts that have already been made to the agency’s budget, not to mention the number of agency employees, contractors, and partners that already are (or are likely to be) affected (including by additional firings, reassignments, and reductions in workforce) over the next months. Even if Secretary of State Marco Rubio, who has a long track record as a senator of supporting action to prevent and respond to mass atrocities,13 were able to marshal enough financial resources to deliver atrocity prevention initiatives and related research, analysis, and programmatic activities, the loss of expertise, institutional knowledge, and human capital arising from the administration’s current approach is inestimable and will be extremely hard, if not impossible, to replace.

The same is true for any other agency that is involved in supporting atrocity prevention efforts by implementing and operationalizing U.S. government commitments to this end. Although their true scope remains unclear, such measures—including personnel reassignments and dismissals; the disbandment of interagency working groups (such as that responsible for gathering intelligence to inform U.S. policy on atrocity crimes); budget cuts; and within-agency reprioritizations—have already affected and will continue to affect the Department of Homeland Security, Department of Defense, National Security Council, FBI, and much of the rest of the intelligence community. Moreover, the reduction of U.S. government personnel is likely to also affect U.S. diplomatic missions and other operations within at-risk countries. Although the list of U.S. embassies that might be closed has not yet been made public, this is a serious concern particularly for at-risk countries, given that losing an embassy entails a lack of eyes and ear on the ground, as well as channels for implementing policy as required. Meanwhile, cuts and terminations to federal grants and U.S. foreign assistance, unless reversed or otherwise addressed, will cripple the research, analysis, and knowledge generation that is continuously needed to properly inform U.S. government action on the basis of data-driven evidence, to monitor and document ongoing violations, and to highlight the scores of lessons learned yet to be assimilated. Similarly, the impact of such cuts on the local partners the U.S. government would otherwise (and rightly) rely on to deliver many of its in-country programs and activities has already proven devastating (not to mention such cuts’ fatal effects on the lives of the world’s most vulnerable).

In addition, a number of actions the administration has already directed against key institutions, both at home and abroad, raise broader but important questions for the future of U.S. leadership and global engagement, as well as ongoing U.S. commitments to address atrocities, protect civilians, and promote postconflict stability. These include, among others, its reimposition of sanctions on the chief prosecutor of the International Criminal Court, an institution with which (for better or worse) the U.S. government inescapably has intersecting interests across a range of policy priorities and in a number of country situations; its (second) withdrawal from the UN Human Rights Council; its overhaul of congressionally mandated entities; its dismantling of initiatives aimed to support accountability for Russian war crimes; and its current approach to the wars in both Ukraine and Gaza. More broadly, the confrontational approach the second Trump administration has taken toward a range of like-minded partners and international organizations will seriously impede U.S. government efforts to work through multilateral and perhaps even bilateral arrangements as it did in its first term. For example, the administration’s push to review all multilateral agreements to which Washington is party might lead to the loss of access to important forums and agencies that previously offered both platforms to raise U.S. government concerns and implementation partners to carry out its agenda. Tenser relationships with some members of the International Atrocity Prevention Working Group—the microlateral network bringing together those allies (such as Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom) with whom the U.S. government has coordinated atrocity prevention action most closely until now—shows how steps taken in the past three months, unless constructively addressed, will negatively impact the U.S. ability to partner with even its closest friends.

Put simply, unless it reverses course or otherwise repairs the damage already apparent, the Trump administration might have seriously undercut its own capacity to leverage the expertise, resources, and capabilities of the U.S. government’s own agencies and undermined its chances to work with both the multilateral and civil society partners it needs to rely on to deliver on its atrocity prevention commitments. Of course, it is possible that the administration will be able to identify at least some avenues to engage in specific country situations, but these will be limited and (in keeping with its approach during the first term) are likely to be highly selective. That, too, will make it harder, even for willing partners, to join U.S. government efforts given the current global political climate.

Actionable Recommendations

The White House

Despite the challenges highlighted above, the administration can nonetheless still take a number of steps to redress the situation and improve its readiness to deliver on atrocity prevention commitments, regardless of how these might be articulated and prioritized. These steps include:

- Reaffirming U.S. commitments to prevent, mitigate, and respond to atrocities and to hold perpetrators of genocide and mass atrocities accountable by enshrining such imperatives in its next national security strategy (as it already did in 2017).

- Implementing and operationalizing the U.S. Strategy to Anticipate, Prevent, and Respond to Atrocities, and complying with legal obligations to fulfill reporting and operational requirements under Section 5 of the Elie Wiesel Act. As listed under subsections 5(a)(1)(D) & (E) of the act, this includes:

- Conducting a “global assessment of ongoing atrocities, including the findings of such assessment and, where relevant, the efficacy of any steps taken” by the task force or “relevant Federal agency to respond to such atrocities.” This necessarily requires restoring the recently disbanded intelligence working group informing the interagency process of early warning and actionable scenarios.

- Reporting to Congress on “countries and regions at risk of atrocities, including a description of specific risk factors, at-risk groups, and likely scenarios in which atrocities would occur.”

- In furthering such objectives, the White House should utilize early warning data to identify countries immediately at risk and those where risk factors and indicators are present but where mass atrocities have not yet escalated. The second group will require “upstream” interventions (meaning action should be taken before mass atrocities’ onset to mitigate risks or de-escalate). This, too, requires early and actionable intelligence and calls for reinstating the intelligence working group that has been informing the interagency process thus far. In addition, this is an area where the effective dissolution of USAID will become problematic unless its effects are appropriately counteracted, given that it will be much harder to work upstream in places where international development assistance focused on building resilience, local leadership, and other relevant upstream initiatives have been cut or otherwise curtailed.

- In both cases, but especially the former, the White House should also determine which strategies and potential tools could be effective within the contextual factors and country-specific dynamics of each case scenario to degrade perpetrators’ capacity, dissuade them from committing atrocity crimes, and protect populations at risk.

- Interagency communication, coordination, and congressional oversight will also be needed in both cases, but especially with respect to upstream prevention.

- Ensuring that the task force, the National Security Council, and any federal agencies tasked with implementing atrocity prevention commitments are properly staffed, resourced, and safe from cuts to the federal workforce and budget. This includes:

- Ensuring that the task force is composed of individuals at the assistant secretary level or higher (as designated by the leadership of the respective departments or agencies). The task force should also have a clearly identified organizational structure, including the following steps:

- The appointment of a knowledgeable atrocity prevention senior director to the National Security Council to lead the interagency process

- Support staff and supporting working-level roles filled by participating agencies and departments

- Appropriately identified and staffed offices within supporting agencies and departments

- An atrocity prevention adviser positioned within each regional bureau at the State Department to render access to expertise more readily available to all concerned desks

- Reviewing and, where necessary, reversing funding, office, and personnel cuts and reassignments currently affecting federal agencies involved in operationalizing U.S. government atrocity prevention commitments, including: the Departments of State, Treasury, Defense, and Homeland Security; the National Security Council; the FBI; and other relevant intelligence and law enforcement agencies.

- Reviewing and continuing to update and deliver training for civilian, military, and law enforcement personnel of both the United States and partner countries, including by partnering with governmental and nongovernmental institutes as relevant, both at home and in partner countries, preferably in coordination with the relevant regional bureau’s atrocity prevention adviser.

- Developing a clear plan to ensure that any and all losses caused by the State Department reorganization, the dissolution of USAID, and the overhaul of USIP (particularly as they pertain to atrocity prevention commitments) are identified and mapped out and that strategies, policies, and plans are proactively implemented by the State Department, other relevant agencies, and, where appropriate, external partners to offset and counteract their impact on U.S. government commitments and capacity.

- Where necessary, providing a surge in all relevant agencies’ personnel and budgets, particularly those tasked with documentation and monitoring efforts and with enforcement responsibilities, both domestically and with partner countries.

- Identifying strategic, policy, and within-country priorities in fulfillment of commitments and obligations under all relevant statutes and strategies, and proactively identifying research and implementation partners, both at home and abroad, particularly in civil society, to integrate and compensate the current loss of technical, financial, and manpower resources caused by ongoing cuts and terminations affecting federal grants and foreign aid.

- Revitalizing U.S. government commitments and partnerships with like-minded countries, particularly with U.S. allies such as members of the International Atrocity Prevention Working Group, including by proactively and constructively working to identify and address any potential sources of tensions, rebuild trust, and foster good-faith cooperation.

- Ensuring that the U.S. government maintains access to high-level forums, commemorations, and mechanisms, including but not exclusively at the UN, and, where access has already been limited (such as in the case of the UN Human Rights Council), encouraging partner countries to raise key U.S. government priorities.

- Identifying avenues and actionable recommendations to sustain the U.S. government ability to fulfill the “enhancing multilateral mechanisms” and “strengthening relevant regional organizations” requirements under Section 5(a)(2) of the Elie Wiesel Act and the act’s policy statements in Sections 3(2) and 3(3).

- Ensuring fulfillment of Section 3(3)(C) of the act requiring that the U.S. whole-of-government strategy for atrocity prevention include the “effective use of foreign assistance to support appropriate transitional justice measures, including criminal accountability, for past atrocities.” This should include:

- Increasing the annual budget for atrocity prevention initiatives to an amount adequate to ensure that sufficient funds are readily available to deliver on atrocity prevention commitments in all thirty of the most at-risk countries designated in the 2025 Biennial Progress Report to Congress pursuant to the Global Fragility Act.

- Prioritizing the appointment of a knowledgeable and experienced new U.S. ambassador for global criminal justice to lead and sustain the functional and operational work of the Office of Global Criminal Justice, even if it were to be housed elsewhere at the U.S. State Department. The office’s work provides an excellent example of programs that should see a surge in capacity and resources and that could be examined to evaluate possible additional benefits in atrocity prevention efforts.

- Sustaining funding and cooperation with Eurojust, PacificJust, Justice and Accountability Network Australia, and other law enforcement and investigative bodies, including UN mechanisms such as the International, Impartial and Independent Mechanism for Syria, the Independent Investigative Mechanism for Myanmar (IIMM), and relevant domestic, regional, and international courts and tribunals concerned with investigating international crimes allegations and bringing perpetrators to justice.

- Expanding U.S. risk assessments and analysis to align with new and related threats (as set out in the intelligence community’s 2025 Threat Assessment), including:

- The role and impact of various technologies on atrocity prevention, mitigation, and response efforts.

- Any changes that might be needed to U.S. government and partner countries’ strategies to protect civilians and monitor and respond to atrocities to ensure the strategies remain fit for purpose in light of escalating geopolitical tensions, great power competition, and the possibility of confrontations with or among U.S. foreign adversaries.

- This is particularly important in the case of direct confrontation between military and technological superpowers, including near-peer competitors, regardless of whether the United States might itself be a party (such as conflicts involving Taiwan or Ukraine).

- Making additional, substantial funding available to increase civil society’s early warning and research capacities, including in support of the earlier-mentioned objectives.

The U.S. Congress

The U.S. Congress has a hugely important and urgent role to play in holding the administration to its obligations under the Elie Wiesel Act and other relevant legislation and in ensuring that competent U.S. government entities and departments tasked with implementing such commitments stand ready and capable to do so. This includes:

- Exercising the power of the purse and passing a formal authorization for appropriation for atrocity prevention programming, and ensure—through the appropriations process—that sufficient funds are readily available to address, mitigate, and respond to atrocity risks in all thirty of the most at-risk countries.

- Continuing to legislate atrocity prevention, including by expanding the Elie Wiesel Act, country-specific legislation, and other relevant statutes, to ensure that both the current and future administrations remain under legal obligations not only to continue implementing such commitments but also to periodically report to Congress on their progress across all relevant authorities. Country-specific legislation with strong bipartisan support, such as the past examples of the Caesar Act or the Burma Act, can be extremely powerful in mandating the deployment of atrocity prevention tools.

- Exercising congressional oversight, including:

- Over the dismantling, resizing, reprioritizations, reassignments, and cuts initiated by the White House across the State Department and all federal agencies with responsibilities for atrocity prevention to ensure that the adverse impact of any such measures (whether taken or planned) do not infringe on the U.S. government readiness to deliver on atrocity prevention by leveraging the 2025 Department of State Authorization Act to codify this work. This especially includes congressionally mandated entities such as USAID and USIP.

- By holding regular hearings for administration officials, including but not limited to the topic of the White House annual report submissions to Congress.

- By convening hearings and requesting regular briefings by administration officials on thematic and in-country issues regarding atrocity prevention.

- By leveraging future confirmation hearings before the Senate to explicitly ask presidentially appointed nominees and candidates about their plans and commitments to atrocity prevention objectives and priorities.

In addition, Congress should consider:

- Mandating that the task force meets at the assistant secretary level or higher, as well as with regional bureaus directors, at least twice a year; that a knowledgeable atrocity prevention senior director be appointed to the National Security Council to lead the interagency process; and that support staff and supporting roles be filled by participating agencies and departments, including the appointment of an atrocity prevention adviser within each regional bureau at the State Department.

- Mandating the White House to report on progress accounting for the role and impact of various technologies and of escalating geopolitical tensions, including great power competition, on atrocity prevention, mitigation, and response efforts.

- Mandating the White House to carry out a review of atrocity risks and factors that might be present within the United States, including in relation to the potential threat posed by domestic violent extremism (a threat category that was notoriously absent from the 2025 intelligence community’s threat assessment for the first time since 2019).

- Requesting the White House, State Department, and other relevant agencies to provide regular updates on U.S. arms sales and weapons transfers, particularly to countries actively engaged in armed conflict, to ensure such transfers remain at all times in line with U.S. legal obligations under the Arms Export Control Act, Leahy Laws, and the Foreign Assistance Act, particularly including provisions related to human rights protections and compliance, such as those requiring the vetting of recipients of security assistance and the prohibition of assistance to countries that restrict humanitarian aid delivery.

- Advocating with the White House for U.S. engagement around thematic and country-specific priorities and, where relevant, passing dedicated legislation or country-specific appropriations, including but not limited to the following examples.

- Syria: Identify the most appropriate ways for the U.S. government to support the Syrian political transition after the ouster of former president Bashar al-Assad, including national dialogue and policy priorities such as security, reconstruction, the search for the missing, and international crimes accountability.

- Northern Iraq: Particular focus on the regional threat posed by resurging Islamic State forces and the national security threat that returning foreign terrorist fighters might pose to both the U.S. homeland and allies in Europe and elsewhere.

- Myanmar: Continue to support international accountability mechanisms, including those developed to build prosecution-ready case files, preserve and analyze evidence, and bring perpetrators to justice.

- Democratic Republic of Congo: Ensure that previous U.S. government efforts (including engagement through the UN Security Council, the imposition of sanctions, and U.S. security assistance) continue as needed and are effective to prevent further escalation of the internationalized conflict involving both state and nonstate actors.

- Haiti: Given its geographic proximity and historical ties to the United States, ensure that appropriate security arrangements are made within the country to restore order and protect vulnerable populations, including the humane treatment of internally displaced persons, refugees, and migrants.

- Central and Latin America: Proactively and constructively engage with relevant countries, including regarding the ongoing situation in Venezuela, to ensure that appropriate within-country measures are taken to secure the U.S. southern border, while assisting vulnerable populations in a manner that preserves the human rights and dignity of refugees, asylum seekers, and migrants and fulfills all legal obligations to which both the United States and partner countries are subject under domestic and international law.

- Sudan, Central African Republic, Afghanistan, Somalia, and other at-risk countries: Identify the most appropriate means of engaging with at-risk countries designated in the 2025 Biennial Progress Report to Congress pursuant to the Global Fragility Act, to identify the most effective policies and actionable strategies to ensure vulnerable populations are assisted and protected and that the capacity of current and would-be perpetrators of mass atrocities is deterred and degraded.

About the Author

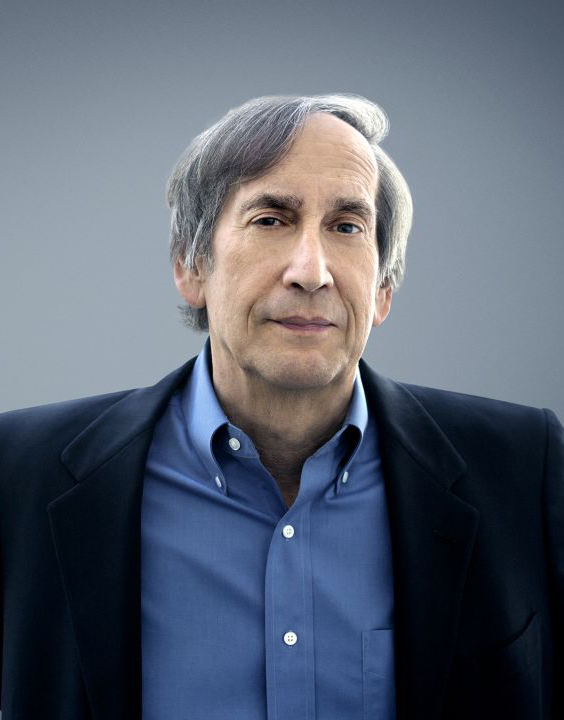

Nonresident Scholar, Global Order and Institutions Program

Federica D’Alessandra is a nonresident scholar with the Global Order and Institutions Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

- International Crimes Accountability Matters in Post-Assad SyriaPaper

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Is a Conflict-Ending Solution Even Possible in Ukraine?Commentary

On the fourth anniversary of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Carnegie experts discuss the war’s impacts and what might come next.

- +1

Eric Ciaramella, Aaron David Miller, Alexandra Prokopenko, …

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

Putin is stalling, waiting for a breakthrough on the front lines or a grand bargain in which Trump will give him something more than Ukraine in exchange for concessions on Ukraine. And if that doesn’t happen, the conflict could be expanded beyond Ukraine.

Alexander Baunov

- Russia in Africa: Examining Moscow’s Influence and Its LimitsResearch

As Moscow looks for opportunities to build inroads on the continent, governments in West and Southern Africa are identifying new ways to promote their goals—and facing new risks.

- +1

Nate Reynolds, ed., Frances Z. Brown, ed., Frederic Wehrey, ed., …