Last month, President Donald Trump’s administration released its plan to reorganize the State Department and reduce the department’s workforce. Many aspects of these plans are concerning—especially the proposed reductions to the department’s highly skilled and dedicated workforce—but the organizational reforms proposed for the Office of the Under Secretary of International Security and Arms Control (whose under secretary, in the department’s organizational naming system, goes by the initial “T”) are not among them.

The State Department created the T under secretary’s office in late 1999, when it absorbed the previously independent U.S. Arms Control and Disarmament Agency. The presidential decision that created T made the position a senior independent adviser to the president on nuclear issues. Their oversight included bureaus focused on nonproliferation, arms control, and verification and compliance, as well as the preexisting Bureau of Political-Military Affairs that builds security partnerships alongside the Department of Defense. However, the vision for a strong T office was never fully realized. The State Department bureaucracy, which elevates region- and country-specific interests over functional ones (such as nonproliferation), consistently pushed T to the margins.

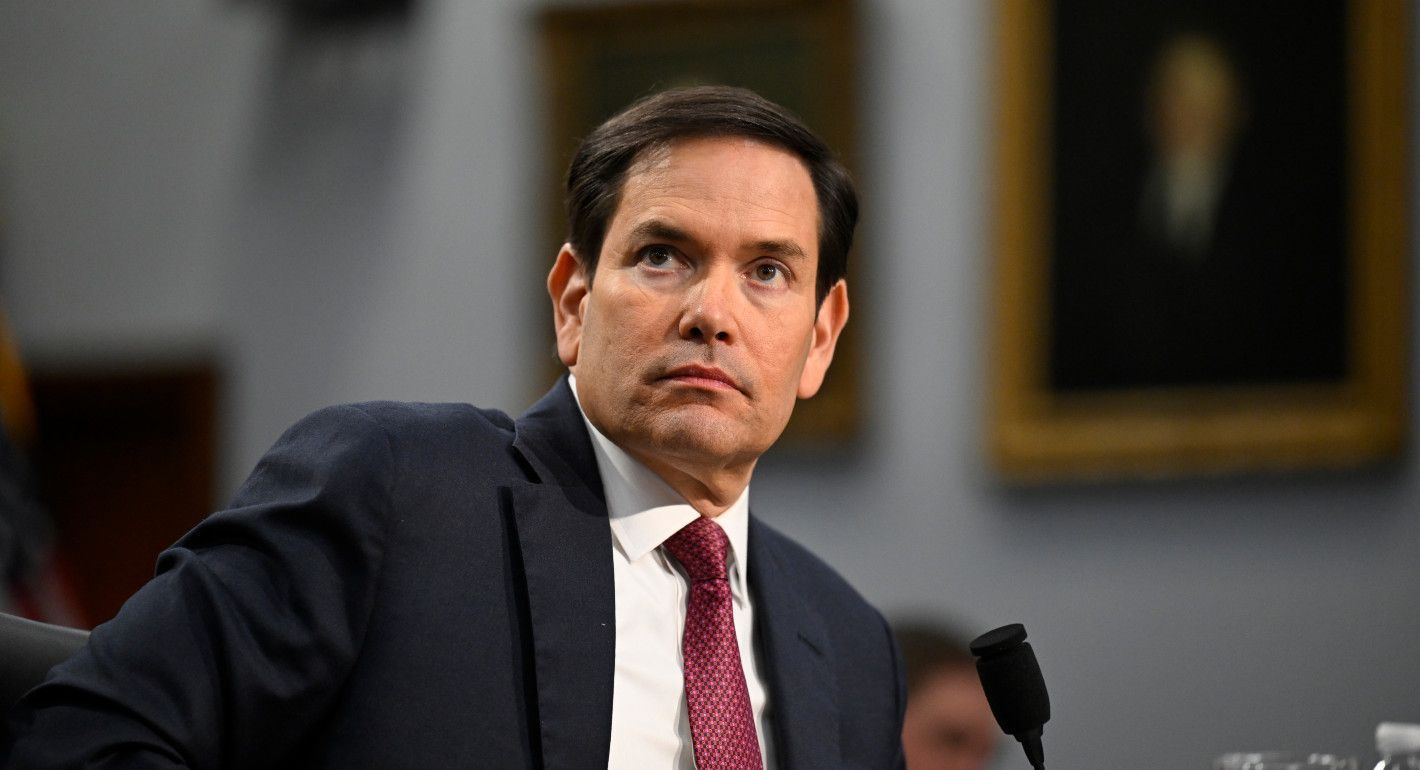

The planned reforms by Secretary of State Marco Rubio are an opportunity to correct this deficiency. The reforms can strengthen the bureaucratic, diplomatic, and strategic effectiveness of the State Department’s international security, nonproliferation, and arms control missions, enhancing T’s influence within the department. That said, important questions remain about how the programs and staff operating under T’s oversight will be resourced.

Rubio proposes three major changes relating to T. First, he wants to merge the two bureaus focused on arms control and nonproliferation—the bureaus of Arms Control, Deterrence, and Stability (ADS) and International Security and Nonproliferation (ISN). Second, he plans to create a Bureau of Emerging Threats within T. Third, he proposes to shift to T the existing bureaus of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs and Counterterrorism (which are currently located elsewhere in the State Department).

The merging of ADS and ISN has attracted controversy, particularly within the nongovernmental nuclear policy community. Past reorganizations have put these bureaus’ workers through box-shifting turmoil multiple times over the past three decades. Moreover, this time feels all the more worrying, given the indiscriminate cutting of other federal workers.

However, reducing the number of assistant secretaries who lead risk-reduction efforts from two to one will not undermine those efforts. The real barriers to progress are Russia’s and China’s disinterest in and disdain for honoring or seriously negotiating arms control agreements. Moreover, explaining to foreign interlocutors—or fellow administration appointees—the mission-driven need for the seemingly arbitrary bureaucratic dividing lines between ADS and ISN can be difficult. (For example, both have offices dealing with aspects of biological weapons and multilateral nuclear affairs.) How well the State Department funds and supports its arms control and nonproliferation staff and functions will matter much more than whether it fuses them.

Rubio’s second proposed change, the creation of a Bureau of Emerging Threats, would build on a special envoy created by former president Joe Biden’s administration to coordinate State Department policy and strategy on AI, quantum, and biotechnology, among other key emerging technologies. The new bureau’s precise role remains unclear, but aligning the State Department’s efforts to address the security challenges posed by these technologies—efforts that necessarily involve T’s other bureaus—should enhance their effectiveness.

Rubio’s third proposed change—giving T responsibility for international counterterrorism, anti-narcotics, and law enforcement efforts—aligns with T’s existing role in arms sales. It would enable T to consolidate control over the State Department’s security assistance programs and vastly expand the office’s programmatic and personnel resources and responsibilities. Indeed, it would lead to a doubling of T’s staffing count at fiscal year 2024 levels—though the administration is proposing major cuts to law enforcement assistance.

If done properly, reorganizing and expanding T could yield several important benefits besides improved coordination within the State Department. The department has struggled to craft a strategic approach to foreign security assistance. Under the proposed reorganization, T would be able to carefully consider the best way to offer the full spectrum of State Department tools. For individual countries, T could propose security assistance packages that include training and arming their militaries, helping them to combat drug cartels and terrorist organizations, and improving their abilities to detect and interdict weapons of mass destructions crossing their borders.

Unifying the State Department’s offerings under T would enhance the United States’ ability to ensure wider security aims. Bilateral engagements with T would become even higher-stakes occasions for partner countries as they would face the possibility of receiving (or losing) critical assistance by agreeing (or refusing) to address other U.S. security concerns. For example, security benefits could be tied more readily and more directly to a country’s willingness to address a nonproliferation priority of the United States.

Increasing the resources and responsibilities under T’s control will strengthen the office’s bureaucratic voice on important international security, arms control, and nonproliferation security matters. In recent decades, both Republican and Democratic administrations have bypassed T on issues that seemingly fall within its mission. Instead, special envoys outside of T have often led key nonproliferation and arms control negotiations and have sometimes discounted or even ignored inputs from experienced subject-matter experts under T.

Meanwhile, State Department officials with a regional focus often fail to see the global security consequences of a given policy choice. For example, the Biden administration in its final days removed three Indian nuclear entities that India has not included among its civilian nuclear facilities offered for International Atomic Energy Agency safeguards from the export control list, which restricts the export of certain goods from U.S. companies. This policy damaged global nonproliferation standards and might have been prevented if T were a more powerful actor in the policymaking process.

T will need a better-staffed front office to seize these opportunities. In fiscal year 2024, the Office of the Under Secretary of Arms Control and International Security had a much smaller cohort than its policy colleagues. The next-smallest undersecretary’s staff was almost 50 percent larger, and the largest was twice T’s size. T also must take better advantage of the Foreign Service, whose networks and culture dominate State Department decisionmaking. T will struggle to sign up the most-qualified Foreign Service officers in one or two recruitment cycles, but over time an Office of the Under Secretary for Arms Control and International Security controlling so many high-value foreign policy tools should be able to secure the best support the Foreign Service has to offer.

Finally, Congress has an important legislative and oversight role to play. It could seek more details from the administration—particularly on how the reforms will retain and support vital arms control and nonproliferation work and expertise—and urge the executive branch to codify its vision for how U.S. security assistance at the State Department should be organized. If the administration gets the T reorganization right, improvements to the department’s approach to international security and arms control will benefit future Democratic and Republican administrations trying to navigate the emerging era of great power competition.