The Disaster Dollar Database is a tool that tracks the major sources of federal funding for disaster recovery in the United States.

{

"authors": [

"Sarah Labowitz"

],

"type": "questionAnswer",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [

"Sustainability, Climate, and Geopolitics"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Domestic Politics",

"Climate Change"

]

}

Trump, joined by Interior Secretary Doug Burgum, OMB director Russell Vought, and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, speaks on disaster preparedness in the Oval Office on June 10, 2025. (Photo by Anna Moneymaker/Getty Images)

FEMA’s Turbulent Year and Uncertain Future

Former agency officials discuss how reforms could reshape the agency and how states should prepare.

For months, President Donald Trump and his administration have been signaling that the FEMA Review Council’s recommendations and final report would set the direction for the future of the disaster response agency. But last week, the meeting to discuss the report was canceled at the very last minute by the White House.Now, the country remains without a vision for how the government handles disaster recovery and resilience in the context of more extreme, more costly disasters.

To discuss this moment of uncertainty, Carnegie senior fellow Sarah Labowitz spoke with former FEMA administrators Deanne Criswell and Pete Gaynor, as well as Danielle Aymond, a disaster recovery and FEMA funding specialist at Baker Donelson, and Michael Coen, former FEMA chief of staff.

Portions of their conversation are below and have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Sarah Labowitz: We thought we would have the report to talk about. Instead, we only have a preview from a CNN article, with four high-level categories. One, will FEMA remain in DHS? Two, more staff reductions. Three is reformulating the public assistance program as a block grant program instead of a reimbursement-based program. Fourth, privatizing elements of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP).

Let’s start with whether FEMA should be an independent agency.

Pete Gaynor: I think moving FEMA out of DHS—this is my personal opinion—is a gigantic distraction. I’m not sure that where FEMA sits counts as true reform when there’s so many other things that need reform. The Stafford Act says that the FEMA administrator is the principal adviser to the president for all things disasters. I’m not sure why it matters where [the agency] sits.

I’ll use my experience in the first Trump administration: Never did the secretary get in my way when I needed to talk to the president or the administration about what needed to happen when it comes to a national disaster. I think the important part of this is focusing on what matters, and that’s true reform. Moving FEMA out of DHS is just wasted time and energy.

Deanne Criswell: Although I agree with a lot of what you said, Pete, I disagree on whether FEMA should move out. I think reform is needed, and moving FEMA out of DHS does not constitute true reform. But I also think that the success of FEMA, the way it sits right now, is based on the relationship that that administrator has with the secretary. You had a good relationship during your time. I had a great relationship with Secretary [Alejandro] Mayorkas. But we have seen with other administrators that that relationship has not been there, and that lack of cohesiveness has really impeded this ability to do their mission.

I think the other part for me, though, is giving FEMA that Cabinet-level position creates a level of authority and responsibility for the administrator that it doesn’t have as a sub-Cabinet level. And the most important reason for that is long-term recovery.

We can talk all day about how FEMA is really good at coordinating the entire federal family in responding to and stabilizing an incident. But when it comes to long-term recovery, the FEMA administrator does not have the authority to direct other Cabinet-level members to do their own mission set. If the FEMA administrator was elevated to a Cabinet level, they would have greater ability to coordinate those other secretaries to accomplish their mission in long-term recovery—one that I just don’t think exists right now and one that we struggled with during my time.

Does it do true reform? No. Does it make a difference? I think it absolutely does make a difference with the overall effectiveness of an agency to accomplish its mission.

Sarah Labowitz: One of the things that was reported in the CNN article was a potential for 50 percent staff reductions at FEMA. What do you think about that?

Michael Coen: I think it would be devastating. Over time, FEMA has increased staff primarily because of the additional missions on FEMA. After the Post-Katrina Emergency Management Reform Act, there were more responsibilities brought to FEMA. Programs had to be created, and staff had to be hired. We’ve seen increased events across the country. Reducing the staff is going to reduce FEMA’s capability. When something catastrophic happens, FEMA won’t have the staff to do all the things that people will expect it to be able to do, then we’ll be rebuilding FEMA yet again.

Sarah Labowitz: Let’s talk about the block grants. I confess that I found the block grant piece hard to understand.

Danielle Aymond: Block grants are certainly not new to the federal government, but they are to FEMA. In the first Trump administration, when hurricanes Maria and Irma hit the territories, we saw a rapid change from the traditional programs of public assistance to almost a forced use of [block grants] for those territories. I think what we saw was the Trump administration’s focus on knowing what they’re buying from the beginning.

For the traditional public assistance programs, response is easy. You can look at debris, you can send drones in the air, you know prices for cubic feet of removal. You know really quickly a lot of your immediate response costs.

Recovery is harder. You have a bridge. It looks minorly damaged—maybe $1 million. You start working on it, and it has damage that you couldn’t see. It becomes a $10 million project. It takes longer. So you add inflation, you add some tariffs, material prices go up, and now it’s a $40 million bridge project, five years down the road.

That’s exactly what we saw in the original administration trying to do in the territories to get ahold of the budget really quick, not wait till you’re ten or twenty years down the road. So I think everybody’s looking to the block grants, but devil is in the details here.

Sarah Labowitz: What do we think about insurability and the role of the private sector?

Pete Gaynor: I think NFIP has been problematic from the beginning, so reform of NFIP is important. But whatever topic we talk about today, the devil is certainly in the details. You could have a great idea, but implementation may be impossible.

There’s some desire to shift some of the risk from the NFIP pool to the private sector. There are already problems in home insurance across the country, especially those states that have disasters year after year—Florida, Colorado, California. I think part of the goal of the NFIP transformation is to ask the private sector to take on more risk. But the insurance industry probably doesn’t want to bear it all. What’s going to end up happening is that they’ll take all the properties with less risk. They’ll leave all the properties with the greatest risk to the federal government, and it’ll still be a problem.

You have to reform NFIP at its core. There is a partnership, I think, with the private sector. But the way forward to make a difference for those who have flood insurance—and more importantly, those who don’t—is key in this whole reform world. But it’s a tall order to just pass off NFIP to the private sector. I don’t think it’s going to happen.

Michael Coen: It’s not realistic. Why is the NFIP a program at FEMA as part of the federal government? Because the insurance industry can’t make money selling flood insurance. So, the key is reducing the federal government’s risk.

It would’ve been nice if one of the recommendations was that FEMA wasn’t going to provide flood insurance policies to new construction. That would be an incentive for developers to build so that the new construction is not going to flood. We continue to build infrastructure that is at risk for flooding, and we need to drive down that risk.

Sarah Labowitz: What do you all think about the future of resilience funding out of FEMA?

Deanne Criswell: To me, the before part of a disaster is the most important part of the mission. Because if we can’t get ahead of the impacts that we are seeing from more frequent and severe disasters, then we are going to consistently be in this loop of respond, recover, rinse, and repeat. There are multiple different studies out there that talk about how much is saved in recovery for every dollar that’s invested in mitigation—but it’s not just mitigation. It’s resilience in general.

People asked me a lot when I was [FEMA administrator]: What do you see the future of FEMA ten or twenty years from now? And my answer was almost always: I see FEMA as a resilience agency, not a response-and-recovery agency. That way our money is going toward saving more lives, protecting more infrastructure, and making people’s lives more predictable because they know they will be safe from these severe weather events.

We are always going to have a need to respond. We are always going to have to have a need to recover. That part of the mission will never go away. But it will only get worse, and we will not be able to keep up with it if we don’t invest in resilience.

Pete Gaynor: I agree. And if it’s the goal of the administration to save money, make disasters cost less, and reduce that federal expenditure—I think we all applaud that. But if you really want to reduce costs, pre-disaster investments are the smartest thing you can do. If you look at what we do in non-disaster preparedness grants, it’s minuscule compared to what we spend on recovery in the Public Assistance program. So if you want to save money, double or triple down on mitigation and pre-disaster investments, because that’s in the long-term where you’re going to save the most amount of money.

Deanne Criswell: Looking back to one of the last hurricanes that I responded to in ’24 in Louisiana—Governor [Jeff] Landry flew me around, showing me the investments that Louisiana had made in helping protect these communities. The damages were minimal compared to what they could have been.

I think the governors really know how valuable this investment is. But it’s really hard to compete for budgets when you’re up against a shiny object—the stuff that’s making the press. And as much as we can work with the media to try to get to a narrative of things like homes saved instead of homes destroyed, really helps to reinforce that narrative.

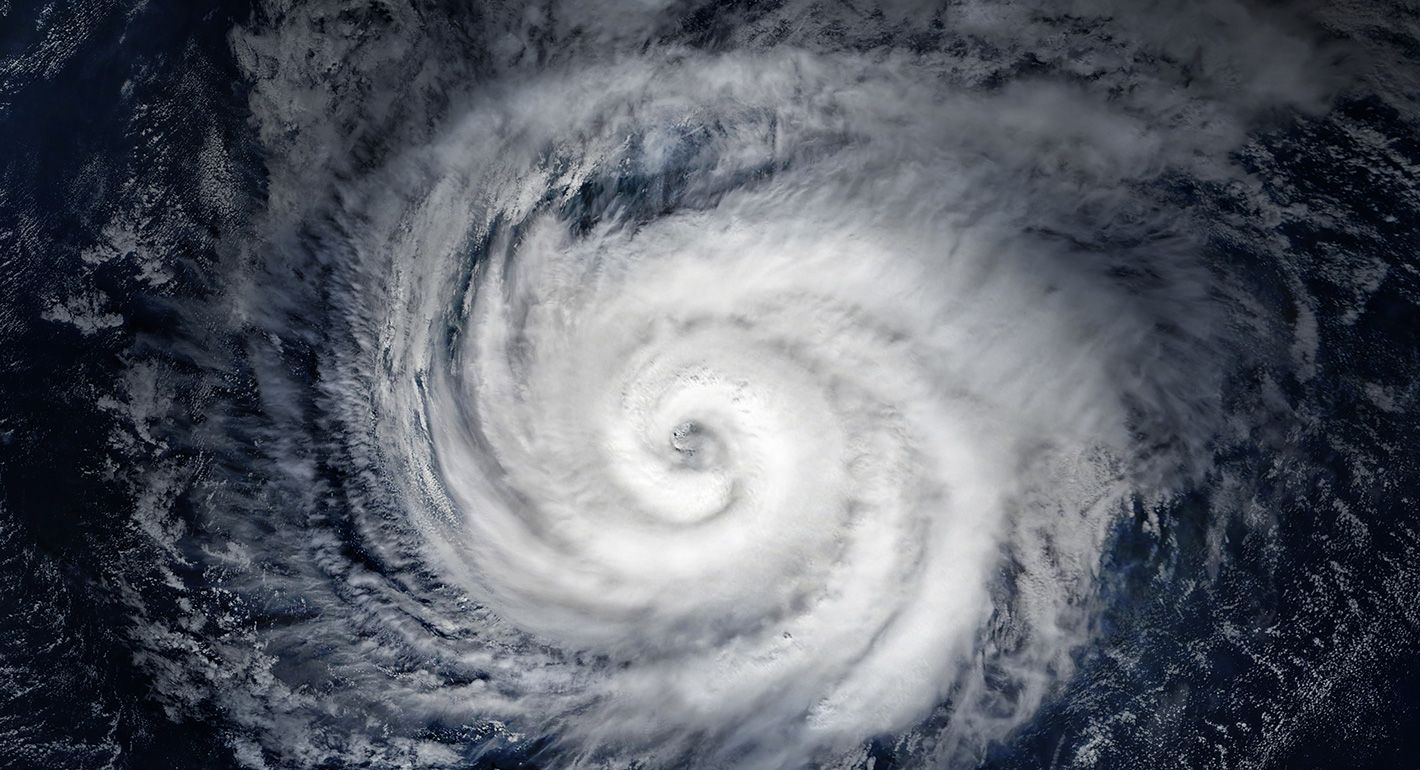

Climate shocks, such as recent, devastating Hurricanes Helene and Milton, open windows when the disaster recovery system can encourage and support adaptation to new climate realities.

Sarah Labowitz: For the former administrators: How do you navigate Washington in this moment to achieve deep substantive change?

Pete Gaynor: The one thing that FEMA—and its employees—need is leadership. In the past [several] months, we’ve had three different leaders, and we have an acting leader today. None of them are professional emergency managers, which the law requires. If I had a magic wand, the first thing I would do is make sure that we had a professional, well-respected, well-experienced emergency manager in that seat to get back to leading the agency. The FEMA administrator job is incredibly hard and incredibly satisfying. But if you don’t have the right person in there, I’m not sure how you actually achieve reform. And I’m not sure how get your employees to follow you in that reform, because you’re going to need every single person who works for FEMA to follow along.

The second thing is that the [DHS] secretary needs to take the leash off FEMA. [Right now, the secretary reviews anything over $100,000.] I don’t know how I could operate as an administrator at $100,000 at a shot. Both Deanne and I have spent billions of dollars on behalf of the American people doing all the right things in a matter of days, so to be hamstrung by $100,000 [limit] makes no sense to me. Disasters are expensive, and you’re going have to spend money to help the survivors who need it.

Then you can get to the really hard part, which is actually implementing some of those reform ideas.

Deanne Criswell: To add on to what Pete was saying: being there for the staff. The women and men at FEMA are the most amazing public servants. [Many of them] have been with FEMA for twenty or thirty years. You ask them why they’d been there so long, and they would always say the same thing: It’s because of the mission. People care so deeply about the mission of helping people before, during, and after disasters.

Whoever is in that role really needs to recognize the value of these people and the reason that they’re there. They care deeply about the American people, and they want to make sure that they reduce suffering, save lives, and help people recover. Whoever comes into that role is really going to have to spend some time reinforcing the value they bring each day.

Daniella Aymond: We also need to think about the states and their leadership. Because when everything hits the fan, those governors and the state emergency management directors are there, right? It is their legal responsibility to act and be responsive.

I spent many years as an executive counsel at Louisiana’s emergency management agency, advising a governor and an emergency management director. Especially when [the disaster] is not a hurricane, you don’t see it coming, and FEMA’s not there. So the states have to be ready.

If anything, regardless of what happens in the legislature and with the FEMA Review Council, the future is pretty darn clear: At least for the next three years, the states have to be ready to respond and even recover—maybe largely on their own. As a state right now, you can’t just be sitting here waiting for the next FEMA Review Council to meet and tell you what’s going to happen. Each of the states individually has to look internally at their own resources, saying: If the cost share was different, would we have been able to afford to recover? And what can we do now [to recover] in the future on our own if we have to? We’re seeing a little bit of that, but not as much as I’d expect.

I would expect to be seeing state legislatures drafting bills that give them that authority, because that’s what they’re going to have to do. A lot of it’s going to be outside of current executive power, which was brought down in a lot of states after COVID in response to the executive power push by governors. Many legislatures have gone back and narrowed that power. They’re going to have to act now, because it’s all happening now—earthquake season is every day, and hurricane season is right around the corner.

For more, watch the video of the event.

Invalid video URL

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Emissary

- Federal Accountability and the Power of the States in a Changing AmericaCommentary

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

- The United States Should Apply the Arab Spring’s Lessons to Its Iran ResponseCommentary

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

- Trump Wants “Peace Through Construction.” There’s One Place It Could Actually Work.Commentary

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan

- Can Venezuela Move From Economic Stabilization to a Democratic Transition?Commentary

Venezuelans deserve to participate in collective decisionmaking and determine their own futures.

Jennifer McCoy

- What’s Keeping the Iranian Regime in Power—for NowCommentary

A conversation with Karim Sadjadpour and Robin Wright about the recent protests and where the Islamic Republic might go from here.

Aaron David Miller, Karim Sadjadpour, Robin Wright