The Disaster Dollar Database is a tool that tracks the major sources of federal funding for disaster recovery in the United States.

{

"authors": [

"Sarah Labowitz",

"Leonardo Martinez-Diaz",

"Debbra Goh"

],

"type": "commentary",

"blog": "Emissary",

"centerAffiliationAll": "dc",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace"

],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"programAffiliation": "SCP",

"programs": [

"Sustainability, Climate, and Geopolitics"

],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"United States"

],

"topics": [

"Domestic Politics",

"Economy",

"Climate Change"

]

}

A woman searches through debris after a tornado hit London, Kentucky, on May 17, 2025. (Photo by Allison Joyce/AFP via Getty Images)

Trump’s Plan to Push FEMA’s Role to the States Will Be a Fiscal Disaster

Many states are not equipped to handle their own recovery without federal help.

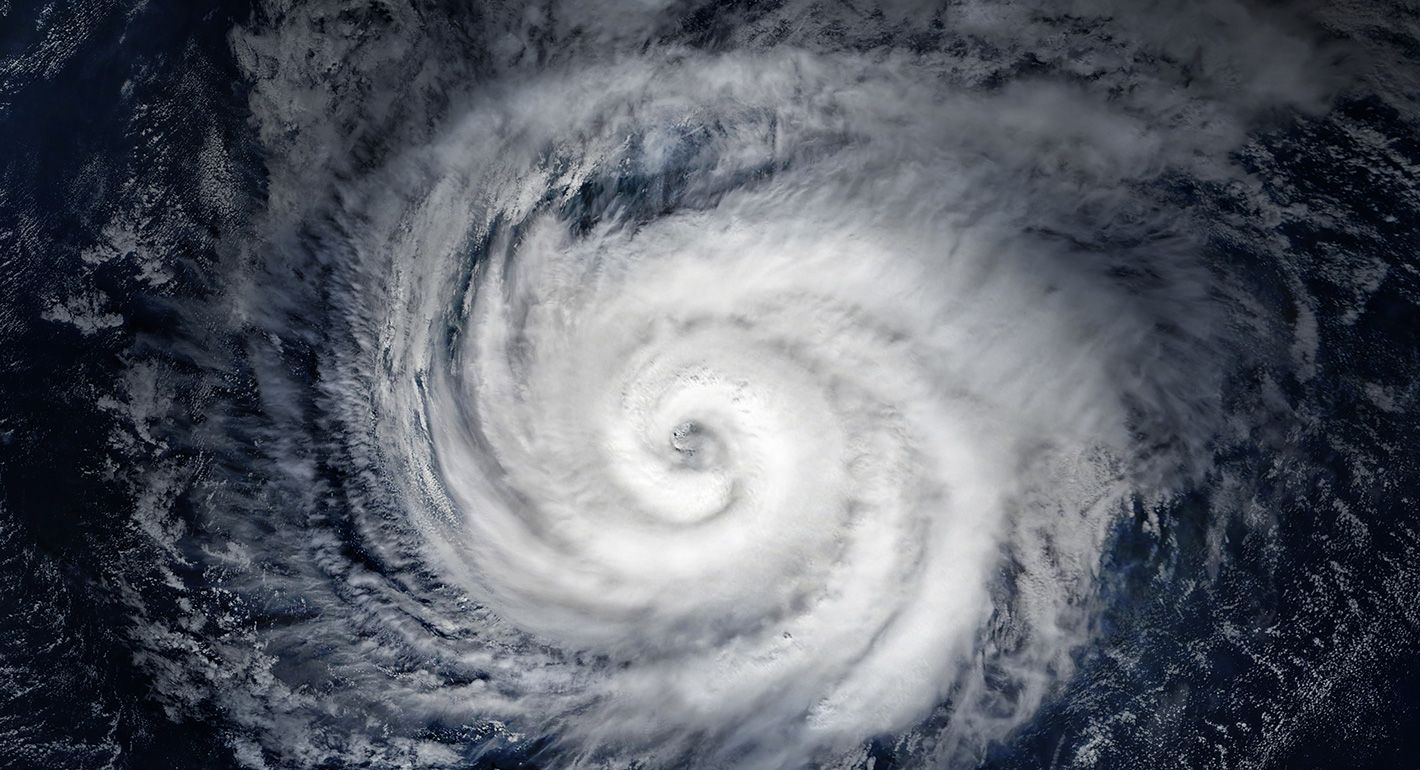

The late spring and early summer are typically a time when the U.S. federal government prepares for hurricane season—the period from June 1 to November 30 that produces the biggest and most costly disasters in the United States. But this year is different.

President Donald Trump and Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem continue to argue that FEMA, the primary federal disaster response organization, should cease to exist. There is no Senate-confirmed FEMA administrator because the White House has not nominated someone who meets the congressionally mandated basic qualifications for the role. Acting Administrator David Richardson still has not produced a viable plan for how FEMA will manage the hurricane season. The agency’s most experienced leadership has left or been forced out—most recently Jeremy Greenberg, who coordinated whole-of-government storm response. And the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) remains understaffed to perform critical weather forecasting functions that allow emergency managers to anticipate extreme weather conditions and position themselves for disaster response.

All of this makes the arrival of hurricane season unusually concerning. But three striking trends threaten to jeopardize a system already under strain: a backlog in federal disaster response requests, an inability of states to fill the federal funding gap, and a shift of accountability to states. Taken together, these factors could suggest major problems not just for the coasts, but for the whole country.

Historic Bottlenecks in Federal Response

In previous years, the federal government has typically reviewed disaster declarations quickly and in a nonpartisan way, and the review process happens in step with the pace of disasters so that the system isn’t slowed down with backlogs. Now, a bottleneck has emerged: Since January, the Trump administration has been waiting weeks or months to approve disaster declaration requests—then approving eight at a time. Instead of deploying FEMA staff and resources to disaster-affected places soon after an incident, staff are stretched thin across multiple incidents at once.

In a normal year, for the two weeks prior to the start of hurricane season, outstanding disaster requests should be a mostly flat line. In contrast, this year stands out for both historically high levels of requests (almost thirteen, compared to an average of four) and for the way approvals are made in a big batch. Both are indicators of major delays in getting help to people in disaster areas.

This kind of delay has practical consequences. For example, St. Louis, Missouri, experienced a devastating tornado on May 16 that killed five people. The administration finally approved Missouri’s request for a disaster declaration on June 9—meaning that survivors and the city were on their own for three-and-a-half weeks. Local first responders have worked around the clock to perform duties—including search and rescue, basic repairs, and damage assessments—without support from FEMA staff or resources.

Quick response to disasters is what gets the economy going again. Parents can send kids back to school. People can go back to work. People can move back home. The delays this year are highly unusual, and we don’t yet know what the economic and social consequences will be of lagging federal recovery support. As they reimagine recovery in 2025, communities in the U.S. may have to start looking to other countries, where national governments do not provide significant levels of post-disaster support. This would mean more reliance on mutual aid, philanthropy, and corporations, with much less consistency across the country.

States Lack Recovery Funds

Republicans and Trump administration officials have repeatedly said that they want states to bear more of the cost and responsibility for their own recoveries. “When you have a tornado or a hurricane or you have a problem of any kind in a state, that’s what you have governors for. They’re supposed to fix those problems,” the president said in June. Representative John Rutherford, a Republican from Florida, echoed the president at a May House hearing: “We don’t need someone to come in and hand-hold us … I can tell you our governor does a fantastic job.”

Rutherford is one of many officials who cite Florida—as well as Texas—as examples of states that are capable of handling disaster recovery themselves. Both experience a lot of disasters and have state emergency management agencies that are well-resourced and -staffed. But their recovery funding largely comes from federal dollars: FEMA bears 75 percent of the costs of recovery when the administration approves a response plan, with 25 percent coming from state coffers. Since 2015, FEMA has sent $7.2 billion to Texas for disaster recovery and $14.3 billion to Florida.

To find out how much money a state could mobilize on its own in a pinch, without having to raise taxes or borrow money, we looked at how many days a state could run only on rainy day funds and leftover general fund dollars (as of the end of fiscal year 2024). The data shows that Texas and Florida do have access to spare cash for an emergency—Texas in particular has a large rainy day fund. But both also receive hundreds of millions of federal dollars, on average, per disaster. Take away all or most of those federal dollars, and those reserves won’t last long—in Texas, Florida, or any of the other eighteen states that received the most federal disaster recovery funds that we examined.

Louisiana is by far the most vulnerable of the states we examined. It receives on average almost $1 billion from the federal government per disaster and has very little cash on hand to deal with an emergency. Without federal funding, Louisianans will be left with little safety cushion to cope with disaster.

But even a healthy state savings doesn’t mean help will come quickly. Despite its high liquidity, Texas took almost two years to activate the rainy day fund for response to Hurricane Harvey in 2017. Local leaders in Houston complained bitterly that housing and school recovery were slowed down by the failure to tap the rainy day fund sooner.

Several other states—including Illinois, Indiana, New Mexico, and North Carolina—have fewer than 100 days of liquidity and are receiving significant federal funds, ranging from $55 million in Illinois to $450 million in North Carolina per average disaster incident. Many of these states are experiencing sleeper disasters—like slow-moving rainstorms—that may not make national headlines but nonetheless cause widespread damage.

This analysis shows that many states—including several that Trump won in 2024—simply are not equipped to handle their own recovery from a disaster without federal help. Governors should be especially concerned about a plan that pushes cost and responsibility onto the states without a runway to prepare and budget for a dramatically changed funding environment.

Who Is Accountable?

Responding to emergencies is one way citizens can assess how their government is working. Right now, the administration simply isn’t prepared for a major disaster—or, worse yet, multiple disasters—this hurricane season. The current hurricane response plan appears to be to use the same plan as last year. But since then, FEMA has lost one-third of its staff, and key programs have been canceled. And if the government is not prepared to respond and recovery stalls out in a major economic center—such as in Houston (oil and gas) or Miami (a major port)—that’s a problem for the entire country.

There’s a reason that Southern governors begged the federal government to nationalize disaster recovery in the 1970s. “The traditional deference to states, localities, the Red Cross and private insurance was simply inadequate in places like coastal Mississippi after Hurricane Camille,” historian Andrew Morris wrote. “Residents of those places, from avowed conservatives to civil rights activists, called for a substantial, and ongoing, federal commitment to construct a disaster safety net under them, and by extension, all American citizens.”

The administration is looking to unwind this federal disaster aid architecture, setting up a scenario where it can blame governors for the inevitable failed disaster response. The administration is also taking steps to consolidate authority for disaster declaration requests within the White House instead of at FEMA. This should be especially concerning for governors. A disaster system that relies on decisionmaking at a highly partisan White House is a recipe for a transactional, discriminatory approach to the most essential and nonpartisan aspects of governance.

This is not to say that the current system is perfect. As two former FEMA administrators have argued, the agency needs reform. Congress has a responsibility to push that reform, and the bipartisan FEMA Act of 2025 is now awaiting formal introduction and markup.

For people who will live through disasters this hurricane season, the political climate that will shape their ability to recover is bad—and getting worse. FEMA’s strength has been in its capacity to spread out the risk of disasters across a big and rich country. In contrast, the administration’s proposal for FEMA aims to concentrate the cost of recovery in a small number of states that simply don’t have the ability to absorb those repeated and growing costs.

The result will be long delays in disaster recovery, schools that don’t get repaired, businesses that don’t open, homes that remain uninhabitable for longer. That translates into slower economic growth, diminished possibilities for families and individuals, and much unnecessary suffering. Like the storms fueled by the Atlantic’s warm waters, we’re hurling toward a future of a bleak post-disaster landscape.

For more, see Carnegie’s newly updated Disaster Dollar Database.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Emissary

- With the RAISE Act, New York Aligns With California on Frontier AI LawsCommentary

The bills differ in minor but meaningful ways, but their overwhelming convergence is key.

Alasdair Phillips-Robins, Scott Singer

- The Trump-Modi Trade Deal Won’t Magically Restore U.S.-India TrustCommentary

Washington and New Delhi should be proud of their putative deal. But international politics isn’t the domain of unicorns and leprechauns, and collateral damage can’t simply be wished away.

Evan A. Feigenbaum

- Federal Accountability and the Power of the States in a Changing AmericaCommentary

What happens next can lessen the damage or compound it.

Mariano-Florentino (Tino) Cuéllar

- The United States Should Apply the Arab Spring’s Lessons to Its Iran ResponseCommentary

The uprisings showed that foreign military intervention rarely produced democratic breakthroughs.

Amr Hamzawy, Sarah Yerkes

- Trump Wants “Peace Through Construction.” There’s One Place It Could Actually Work.Commentary

An Armenia-Azerbaijan settlement may be the only realistic test case for making glossy promises a reality.

Garo Paylan