Jon Bateman, Bruce Friedrich

Why Information Refuses to Be Controlled

In a lively new episode of The World Unpacked, Alicia Wanless and host Jon Bateman discuss what 2025 has in common with 1625, how novels spark civil wars, and why our frantic efforts to tame information often do more harm than good.

Invalid video URL

We’re living through an era of information disruption. Novel technologies like AI and social media are unleashing pent-up social and political energies—releasing floods of new information and triggering intense battles for narrative control.

While most analysts focus on small pieces of this puzzle, Alicia Wanless is a pioneering “information ecologist” who seeks to map the entire system. Her new book is The Information Animal: Humans, Technology, and The Competition for Reality.

In a lively new episode of The World Unpacked, Alicia and host Jon Bateman discuss what 2025 has in common with 1625, how novels spark civil wars, and why our frantic efforts to tame information often do more harm than good.

Transcript

Note: this is an AI-generated transcript and may contain errors

Jon Bateman: Throughout my whole life, I've watched the U.S. and other democracies become more and more afraid of information. Oftentimes a new technology is cast as the threat, from violent video games to email scams to social media bots and now AI. At other times, it's the rise of a disturbing new set of ideas like populism, extremism, or nationalism. Always fusing with technology in frightening new ways. But you're about to hear from someone who has studied all of these phenomena and thinks that we've gotten it all wrong. Alicia Wanless is the author of a terrific new book called The Information Animal, Humans, Technology, and the Competition for Reality. She argues that in our focus on an unending series of specific information threats, we're missing the forest for the trees, literally. That we need to think about the complex ecology of information, where, much like the natural world, our attempts to intervene often backfire or cascade unexpectedly. In a fascinating and sometimes personal conversation, we touch everyone from King Charles I to Elon Musk. I'm Jon Bateman, and this is The World Unpacked. Alicia, welcome to the podcast.

Alicia Wanless: Thanks for having me, Jon.

Jon Bateman: So we're gonna talk about the big things today. Social media, AI, the fate of democracy, the rise of populism. But you have a somewhat different perspective that you take on those than lots of other people who've been debating these for years. And I heard you recently call yourself an information ecologist. And you're studying something that you call the information environment. What is that?

Alicia Wanless: Well, the information environment is this broad global space in which information can exist.

Jon Bateman: So we're part of the information environment right now. A lot of people are watching us on YouTube. They might be listening to us on Spotify. And I guess the notion of an information environment is that we're a part of this huge, interconnected tapestry that you're trying to study.

Alicia Wanless: This all comes from physical ecology, which is a field of study that looks at ecosystems. And basically that is an organism's relationship to its surrounding environment. And often what happens in looking at aspects of the information environment, we look at it in pieces. So you've got great research around media studies, but it's looking specifically at like news media or social media, or somebody might be looking at a specific technology.

Jon Bateman: So you're trying to make this a more holistic conversation and it's interesting when I talk to people about these issues, they will often fixate on particular threats. So it could be bots, AI slop, campaigns run by foreign intelligence services, the Russians, the Iranians. It's very much a kind of search and destroy attitude of who are the bad guys? How can we go out and stop them? What's missing from that picture? Because there are bad guys out there, but what are we missing when we take this threat approach?

Alicia Wanless: Right. So often what I find is that we're moving from like bubble to bubble. So whatever gets the media attention. So, you know, back after 9/11, it was extremism and then disinformation. And it's often connected to certain technologies that are also new or on the rise. And when we put all of our emphasis on doing case studies, trying to understand that specific phenomenon, we never really get ahead to understand the environment where it exists. And so we don't really understand how that works in the context of everything else that's happening. And I think we leap to big conclusions, particularly around causation, because we just don't understand how that system is functioning.

Jon Bateman: You've got remarkable and very deep case studies in the book going back to the English Civil War, the Peloponnesian War, The U.S. Civil War, we're going to get into some of that. But I want to take your invitation to zoom out and look at the contemporary information environment. How do you see it? Because I think when I talk to people, whether it's friends, family, even politicians, elites, there is a pervasive sense of and of kind of continual degradation. Whether you're worried about the rise of hate, the rise of false ideas, rumors, or just apathy toward truth, I know almost no one who is excited or happy with today's information environment. Is that how you see it? What would a holistic view tell us about where we are now?

Alicia Wanless: The national information ecosystem in the U.S. today is one that is very diverse. It's very complex, it's large and sprawling, it's very open. The news media, which is mostly corporate, right? Like it's corporate interests, and so that is a business model. They are also trying to get attention and they have different interests that they may be trying to push depending on that. So it's kind of fractured. Your public media is not well-funded and massively under- and then, add to that, you've just got different types of education across the country that are not standard. So, like, are people actually being brought up with the same reality or any kind of shared reality? So, I can understand why people are feeling dissatisfied with this. I think the one consolation I can offer is that we have been here before. This happens often when a new technology is introduced that changes how we experience information and that accelerates the creation of it and distribution of it. And there tends to follow a period of pollution and new ideas, but that puts us in this period of competition.

Jon Bateman: Yes. And you talk about and write about these information disruptions that break up whatever patterns or flows were there before, reform them, and then lead to kind of intensified competition as some power vacuum occurs. So if you think about comparing our contemporary world, The fracture and the intensity of competition you just described Is there another time and place in particular that most reminds you of what we're experiencing today?

Alicia Wanless: I've been thinking a lot about Charles I in the sense that, in the sense that—

Jon Bateman: Historic English king

Alicia Wanless: Well, yes. So historic English king who was not necessarily, he wasn't meant to be king. He only became that because his elder brother died, but he was a deeply thin-skinned person. And when he comes to power, he gets upset with parliament because they're not doing what he wants and it's not easy for him. So he enters into this period of personal rule, where he dissolves, he prorogues parliament for a long time. And also what he did was that he really cut himself off from the people. Like no monarch is really tied to the people, but in that system there was an aristocracy that would go back to the estates and there would be a feedback loop between the estates through the nobility to the king that then would function as this feedback loop. But he cut it off in favor of favorites, court favorites, and he sent all of the aristocracy back to their estates and tell them they couldn't come to London.

Jon Bateman: A lot of parallels, a thin-skinned personalist ruler, check. Trying to go around the legislature, check, and you're building toward a story here that I think has something to do with information and technology and efforts to control it.

Alicia Wanless: So what happened with Charles was that he is, you know, coming at a period of time where you've got growing printing presses. Like it's still quite a long time after the innovation, but it took a while to come to England and develop, in part because of control over who could have a printing press, but also because printing, developing paper was very expensive. And it was very slow to develop as a domestic resource in England. So that also helped slow it down. So Charles really tried to control that, as many leaders did before that. And what he really wanted to do was control messaging. He was very fearful of a particular group, the Godly, who were pushing for a more extreme version of Protestantism than he wanted. Okay. And it's playing out in the pamphlets. So these pamphlet are a new form of communication, which are like short printed publications and it's, they're dueling here. And Charles is really trying to control that as well. He actually cracks down on a few of the propagandists, let's call them, who were proselytizing for a more extreme form of Protestantism and cuts their ears off, which was deeply unpopular as well.

Jon Bateman: You don't say. So at that time, I'm sure these pamphlets, you might've had elites walking around and saying, this is paper slop, right? These are low quality memes. So there was a kind of information panic and an effort to suppress it.

Alicia Wanless: Because the pamphlets were also pushing fears of the papal conspiracy to return England to the Catholic Church. And this was pervasive and it was like wrapped up in fears of the end of the world. It was very millenarian, a belief that the Pope at the time was the Antichrist at the times. So this was all fueling these crazy fears. And also some of those pamphlets were just like infotainment garbage, like stories about deformations and, like, just horror stories, you know? So I do think that probably there was an aspect of this when people were looking at this saying this is absolute trash, why are you believing it? And you have a growing body of tradesmen, apprentices, who now are literate because of the Reformation. And so they're partaking in this slop, essentially.

Jon Bateman: Somebody might be listening to the story, and they might be identifying all these clear parallels between the 21st century and the 17th century, across different times, different technologies, different social and political conditions. And they might think to themselves, okay, there's nothing new under the sun. We're not in a time of accelerating spiraling change. This is just a recurrent, eternal phenomenon. Humans have always sought to exaggerate, lie, manipulate, or just contest in this information environment. So really nothing particularly interesting or concerning is happening today.

Alicia Wanless: Well, I mean, it is concerning because we are trapped in, we are right now in the midst of a worsening information competition where one side clearly seems to have believed it was in it like since the fifties, right? This is emerging from a, like a conservative movement that felt that, you know, that there was liberal capture, whatever that might've meant. And they've very systematically gone about creating an information ecosystem as it were in tandem to what they perceive to be the mainstream one. So that's been going on at least since the 50s, and you can see a trajectory from William Buckley and like creating publishing presses and stuff like this. I think there are people on the other side who didn't quite realize they were in an information competition until recently. And so what I think will happen now and what we hear calls for is that the answer will be to do more of what the other side is doing. So add more to the information ecosystem, produce more content for your side. Does it matter whether you're telling the truth or not? And really try to win people over to their side. So I think what will happen is this will probably get a lot worse before it gets better.

Jon Bateman: Yeah, so just contemporary examples, right? The Democratic Party in the U.S. and left-wing forces spent years hyperventilating over the rise of figures like Joe Rogan. Now they're starting to see the power of those people and then there are calls everywhere for where's the liberal Joe Rogan, right. So as you say, kind of going from an effort to gatekeep and suppress to saying, well, if you can't beat him, join him.

Alicia Wanless: Right. And I mean, this is something that Americans have actually experienced before. Because if you look back to the Civil War, what happened with abolitionism was that there was a massive production of information of different types. You have novels that are promoting that particular worldview. And then as that grows and the popularity of that is gaining, you get a response in the southern press. To do the same. So you have like matching fictitious stories that are arguing for their point of view. You have newspapers that are, right? So in this duel, right, it adds more fuel almost to the fire.

Jon Bateman: Right, Uncle Tom's Cabin and then all these kind of anti-Uncle Tom novels and then President Lincoln is purported to have said, oh, this is what started the Civil War. We've talked about the pervasive doom and gloom, a more polluted information environment, a more fractured information environment. Maybe degrading or changing in ways that we are frankly concerned about. As I was reading the book, I thought to myself, well, who are the winners in this contest? What would they say? I think the winners would include the big social media companies that are profiting out of new forms of communication, the people and entities that are succeeding on those platforms, whether it's a populist politician or even just a small business, and then the users who support those people, right? So adherence to Donald Trump's movement, or even people who are kind of at the margins of society have rare diseases, they're banding together. So these forces might have a very different view on today's world. They might say, well, nothing bad is happening. What's actually happening is the collapse of an information monopoly that had been held by a kind of decadent elite. And now it's becoming possible to connect across time and space without getting anyone's permission, to speak truth to power, and to speak about formerly taboo ideas that are now becoming acceptable to discuss in these spaces. What do you make of that?

Alicia Wanless: Well, I mean, I think if you look back historically, there was a time in which those things were acceptable to talk about, right? That was the norm. And then there was a cycle in which there was discussion around that not being the norm

Jon Bateman: Yeah, maybe talking about traditional views on gender, race, sexuality, things like that.

Alicia Wanless: And then also I think it's kind of funny to hear like the tech giants being described as maybe not being the elite that is not the monopoly that is allowing certain types of conversation because they have a lot of control, like immense amount of control. And so did the media and the media wasn't all monolithic, right? So there's different sides of that. I think the one thing to me is that again, looking at the longer-term view, this is a cycle and who's winning now may not be who wins tomorrow. Right? You can only be the incumbent and the underdog overthrowing something for so long before you are the ruling elite.

Jon Bateman: We've seen that happen very vividly with the big tech giants like Google and Facebook, now Meta. If you are old enough to remember movies like The Social Network and the early days of Facebook and YouTube, these were very much understood as disruptive forces, as the assaulting the information incumbents. Now, the CEOs of all these companies were sitting behind Donald Trump but his inauguration, it's impossible to deny that they are now part of kind of economic and political establishment. Then you got figures like Elon Musk who almost was serving as a co-president on the backs of some of his digital activity, but he's still more of a disruptor in many ways. Who do you see as the contemporary disruptors that are maybe coming up behind this previous generation of companies or information entrepreneurs and how might they migrate to become more of establishmentarian.

Alicia Wanless: Well, I think the question is, how long will some of these current disruptors who have now turned to practically being the establishment, how will they persist? I know that this is a risky guess to make, but how sustainable is the social media business model? There's a reason why everybody's pivoting to AI, because at some point there's a question of whether the advertising model still works. And whether advertisers will continue to buy into that model if they're not seeing returns on it. And having run campaigns in the past in a previous job, I would argue that social media ads were never really that effective. So I think that it's kind of a house of cards. And then with the massive pivot to AI, that's a lot of investment to put into something which, I mean, I know you're very big on AI advancements, but I don't remember seeing a technology that is being pushed without actually solving a particular problem. Like I look at the MOU with open AI and the UK government to agree to find ways to apply it. Like that seems to me like a little.

Jon Bateman: Well, you know, people sometimes say, Jon, your podcast, it's so pitch perfect. Is it fully AI generated, partially AI generated?

Alicia Wanless: I'm totally AI. I don't even exist.

Jon Bateman: Actually, I want to let the fans in on a little secret. This is artisanal computer graphics here. So we've got like the Pixar team, those sort of folks working on this. It's a very traditional style of computer production. I want come back to AI, because this is in many ways the information frontier that has become the focal point of anxieties, hopes, and much of the information conversation. But before we do that, I wanna pull the thread on what you said about social media advertising. You mentioned this recurring concern that personalized digital ads are actually not as effective as people might think. This may sound like a niche topic, but it's actually at the core of what we're talking about, which is, are the most advanced forms of persuasion actually magic bullets that we should be living in fear of? Or is some of this a certain amount of snake oil pushed by vested interests who want us to believe that it's very easy to persuade people of many different things online.

Alicia Wanless: Right, both things can be true at the same time, right? Like we should be wary of something that wants to, you know, persuade people all the time, because we don't have a lot of lines in the sand around where the amount of persuasion goes too far and takes away people's autonomy. Like that seems to me a conversation and an assessment that really hasn't happened. And like, I wrote an article about that years ago. Right? Like how far does behavioral advertising technology take it that people lose their autonomy? And that's key for the legitimacy of democracy, right? They have to make free and informed decisions. So I think that that is a big open question, which means we should be wary of these technologies. But that doesn't necessarily mean they're as good as they're being sold. Right? I do think that there is a great degree of promises that are made in the whole realm of marketing, advertising, strategic communication, making promises of winning hearts and minds and getting people to do things that may not actually be based on reality?

Jon Bateman: There are hundreds of billions of dollars being spent on digital advertising every year. There are billions of dollars just in the United States spent on electioneering communication each year. My sense is there is not a hard science that proves that this is efficacious and that to some extent it's an open question whether the emperor wears no clothes or has some clothes.

Alicia Wanless: I mean, there's lots of great research on persuasion, right? Cialdini comes to mind. But it's kind of like a narrow subset of psychology. And the question is whether it can actually be replicated. There's a lot of issues with replicability in like comms studies, in social science, in this computational social science. Like all of these places are all struggling with that, in part because of the data that sometimes gets used or the nature of the experiments.

Jon Bateman: It's a bit of a microcosm for this whole ball of wax, because you've got a couple groups of people. You've got the wonks and social scientists and nerds like you and me on one side saying, actually, there's no data to support this. Meanwhile, massive fortunes are being built by the companies and investors who are charging forward and building the new future, which I think brings us to AI.

Alicia Wanless: Well, I was just going to say your entire economy right now seems to be propped up by an AI perhaps bubble.

Jon Bateman: That is very possible on this point specifically about AI, you know, I said before that I rarely meet anyone who is excited about today's information environment. Actually, there is an exception to that, and that is people who are working in AI companies and people who are AI research scientists who paint a very utopian view of this technology that I think we can understand as a theory of information. What these people are saying is that we are producing a new set of cognitive tools that will organize the world's information and put vast sets of ideas and reasoning capabilities in the hands of scientists who will cure cancer, patients who will understand their diseases, anyone who wants advice on an expert topic. Maybe in the future, one person can build a billion dollar company because of the information reasoning capabilities that are being generated and democratized. What do you think of that?

Alicia Wanless: Well, it sounds a lot like the promises of the internet in the 90s, right? Like it's going to build a utopian society and it's going to answer everything. Okay. It is possible that AI will help solve many problems. Humans using the tools may be able to solve problems faster. I think hoping that it will just do it on its own is maybe promising something that can't deliver and is perhaps going to lead to failure. In particular with AI, what I am most concerned about, and I have always been an early adopter of technology and I do love a lot of technology, I am wary of this one because what it is doing is more than before replacing cognitive function and the brain is a muscle. You have to exercise muscles for it to continue to function at the level that you're hoping it to. And I think we've already seen that a dependence on using Google search. And digital technologies to provide immediate answers has left us without critical skills like navigating.

Jon Bateman: I agree with everything you just said, critical thinking is a muscle that may be atrophying with AI. Let me give you the other side of it, which is that there has been a history in the digital age of new sources of information that initially are seen as very concerning, but later are adopted as some of the best ways that people can inform themselves. Wikipedia would be one of the classic examples. We were all taught in school if you're a person of a certain age.

Alicia Wanless: I was going to say, we were. I know, right. Yeah.

Jon Bateman: People of our cohort were taught to avoid Wikipedia. Now increasingly, it would be something that we would suggest that someone check out as like a first stab at a broad topic. I would say for me, ChatGPT has become the same thing. If I have a family member who doesn't understand what a doctor is telling them or has car problems and they're having trouble getting good advice, my mom the other day got what appeared to be a scam email message, and she did exactly what I would have hoped she would do, which is she asked ChatGPT. So is there another side of this, which is that we actually are building tools that can give types of answers to questions that could not have been readily found before.

Alicia Wanless: But you could, you could Google search that. I mean, every time I would see some fake post that was coming up in social media about, I don't know, post this thing so Facebook can't steal your data and you tell them that you don't agree and that was never a thing, you could just copy that text and Google it and find out that this was like a scam that, not even a scam, but just some sort of weird thing that was going on before. And then I would tell my relatives, like, please stop doing that, it doesn't exist, here's why.

Jon Bateman: I think what makes me suspicious of my own views sometimes is I see this in myself and I see it with others. Is there a tendency to want to freeze in time whatever technology we grew up and became comfortable with, but say no farther than that, right? So for example, like someone like me, I grew up with TV and then later the internet. And I also grew up a certain amount of social panic around those things too. People were worried about.

Alicia Wanless: Santanic Panic! I know.

Jon Bateman: I know the satanic panic and the boob tube and violence on television video games and then eventually the internet. And so I then acclimated to those things and said, okay, that was all silly. I'm glad I had all of these resources. But now that I am of age and I'm seeing changes and further disruptions. Okay, no more. How do we avoid a kind of present-ism? Does that make sense or almost you could call it a kind conservatism the thing the things of my past were acceptable and that the parents gnashing their teeths were wrong, but now I'm the parent.

Alicia Wanless: Right. I think that there's a question about how we roll out tools, again, that may change how people engage with information. I don't think that we needed to, in the argument of we'll be left behind in competition, roll out general, you know, ChatGPT type AI on the internet for everything all at once into a sprawling, messy, what is a global information environment. Was that necessary? Or could we have done a little bit more testing to understand. How it might impact things like cognitive development, especially for young people and adults. We could easily have continued to roll it out in closed information ecosystems like hospitals because it's much easier to study and measure how that changes, say, how a doctor makes diagnosis. And by the way, there has been a study that's come out that suggests that it's actually leading to a less ability, a degraded ability for doctors to make cancer diagnosis, right? So, we should be careful of both ways. One, saying no more technology, we can't have any more, and just saying no outright, and also being super optimistic and not seeing that it will be abused because every technology is going to be abused.

Jon Bateman: Whole nother conversation about medical uses of AI, and I will defend to the death my ability to bring ChatGPT into the doctor's office. We had it with us in the delivery room. What I will say though is, what I'm hearing in your answer is this return to the ecological metaphor. Change occurs in the natural world as well. Species die, they go extinct, others arise, but that can only operate at a certain pace. And if you have a flood of an invasive species or an asteroid crashes and kicks up dust all over the planet, you could have catastrophic effects on the ecosystem. Is that how you see what's happening now with the rise of social media, AI, smartphones and a package of invasions into our information environment that are just happening too quickly?

Alicia Wanless: There is a difference between the information environment and the physical environment. The physical environment did start out natural, we screw it up, right? Like we intervene and we can't necessarily really control it as well as we think we can. But the information environment, well it started naturally in terms of us developing communication and us just being beings where information is encoded in us, right. It's also artificial. Right? We construct elements of it. We add new technology. So in that, we have an ability to create systems to a degree. And we should be cognizant of that and not just throw up our hands and be like, oh, there's a new technology, what can we do about it? And like, regulated after the fact, I think we can get ahead to say, this is how the system's been working to this point, we know there will be new technology that seems to be, unless we destroy ourselves and get a massive setback, there will always be a new technology that's added that's going to cause these reactions among us. Some are going to be utopian, some are going to be, you know, absolutely catastrophic. And in that, we can start to plan because we know what our behavior to it will be. And if we get a better sense of the system, then we know how it potentially might change things.

Jon Bateman: Let's talk about the solutions that people have proffered to all of the issues that we've been talking about today, the loss of truth and trust, the rise of extremism, the fracturing of the information ecosystem. You are very critical of the impulse that people have to do something in response to these problems, to just rush out and implement a solution without full understanding of it. I want us to maybe walk through some of these some things that are often proffered and just get your take on. Does this work? Is this a good idea? So one is more gatekeeping. So there's a digital version of more gate keeping, which is deplatforming people, content moderation. There's also a physical version of it. People will say, you know, parties, political parties need to go back to restraining who can run. Maybe we need to have less direct democracy, more filtration at elite levels. Do we need a return to gatekeeping?

Alicia Wanless: I mean, if I look at the case studies, I'm not sure that gatekeeping is going to get us out of that problem. You could try to foster social norms that may take politicians back to not outright lying and benefiting. I'm sure in the current situation that that isn’t going to happen or be reasonable. And again, when now there seems to be an awakening that at least two sides are involved in an information competition, there will be a lot less willingness. To want to take that path on the one side where I think they might have been open to having that kind of a norm, right? I think if it's in the context of trying to control information, that is nearly impossible. It was difficult in Charles's time when you only had like 20 some printing presses, but you also had printing presses. That were being used in Scotland that couldn't be controlled, that were dumping more information in, and he couldn't control the information ecosystem then. And I don't think even with more technology that we'll be able to do that now, because you can't control people and their ideas and their talking. There's so many levels of transfer.

Jon Bateman: Yeah, so just with Donald Trump, very specifically, there were lots of efforts to deplatform him. He was taken off of online social media platforms. Even at the time, people were saying, is this going to backfire? Could it boomerang in another way? And so we might not have expected specifically that he would have created his own social media platform, but there was an understanding there were alternatives. And yet it went so much farther than I think anyone was predicting, not only in terms of the reelection of Donald Trump but the actual reconstruction of a platform like X from Twitter, in part motivated by people with money and concerns about the Ancien Regime of content moderation. So it does speak to the difficulty of predicting the effects of these actions.

Alicia Wanless: Yes and no. So by the time disinformation is a problem in an information ecosystem, it's an expressed idea that people believe. And by the time you've noticed that it's a problem, that means that there's a certain number of people who believe that idea. And it's not just about preventing them from spreading it. You're now talking about having to change their mind, which gets really slippery quickly for democracies and any other type of government as well. And people don't like that. And then it will be politicized. So I think it was predictable in a way.

Jon Bateman: Yeah, I mean thinking again of this ecological metaphor, which really is more than a metaphor.

Alicia Wanless: I'm hoping it will be, eventually.

Jon Bateman: So once an invasive species has taken root in an ecology, not only is it very difficult to uproot, but it's almost like a cascade of interventions are required. More and more violent, extreme action is needed. In the U.S. right now, there's, I guess, this big controversy of these two owl species. One, due to human activity, has taken over the ecosystem of the other. And so now it seems like the best solution people are coming up with is just that we, kill a bunch of owls like mass slaughter. So it's not easy once these ideas are animals right take root. Let me ask you about another thing that people often propose which is education in various forms. So sometimes you'll hear people say very specifically we need media or digital literacy. We need to teach people how to navigate this information environment. How do you spot a scam? How do tell when a politician is lying to you? Other times people will say, well, it's just critical thinking. You know, we did teach critical thinking in schools. We need to go back to the social sciences, English lit, whatever it is, teach people rhetoric, the classics. What do you think? Can we educate our way out of this problem, either for adults or for the next generation?

Alicia Wanless: I mean, I think that education is crucial and I think that we have to separate education from media literacy. Media literacy is like a form of education that's included in curriculum and sometimes outside of it. And as you know better than I do, because you did the literature review on this one, they're widely varying in terms of the programs and so there's questions about efficacy and where it gets rolled out. But I think that education alone will not be the answer. If you look at, and here I'm going to take a flying leap from things that are not in my book, but like revolutions that often, when you have a growing body of people who are more educated and then their needs are not met based on these new expectations, things can go wrong. So this is again, why we have to look at these things very systemically because not only do you need that education, that population to be educated, but you're going to have to have. Circumstances that are going to now meet their changed expectations. So if your economy can't deal with that, you're bound to have a problem.

Jon Bateman: Yeah, I mean, you would know from your work in counter-extremism that a number of people who are radicalized into Islamic jihadist terrorism actually were highly educated. We had 9-11 hijackers who had medical degrees and the like. It's not a pure inoculation. And even now, with the rise of what people are calling AI psychosis, you know, AI delusions propagated by large language models, There are Billionaires or at least centi millionaires who are actually falling for some of these things

Alicia Wanless: Mm-hmm, of course. I mean, I think that's been a misconception the whole way through, and I think it's also been a way of trying to explain things away easily. Like, oh, the people who fall for this are just somehow uneducated or dumb.

Jon Bateman: So then the final maybe group of solutions that I hear very frequently, you could say, we just need more good information and we can support it in different ways through policy. So for example, let's bring back libraries. Let's invest in local independent media organizations. Let's replenish the public campaign finance system. Or reinvest in public media like the BBC, you know, the CBC, NPR, PBS, does that work? Can you combat bad information by adding good information back into the system?

Alicia Wanless: My guess would be no, not directly. That would not be the magic solution to this problem because it's supply and demand. If people don't actually want to consume that, then it doesn't mean anything that you've introduced it in there. I will say clearly, I am a proponent of public media. I am proponent independent media as well. And I would question how independent most of our media is when it's a business model. I also think that it is important that governments communicate. You mentioned libraries. I think that libraries are actually one of the biggest overlooked opportunities for building greater social cohesion, not in the traditional sense. But if we look at a country, I think Oslo has one, but Helsinki in Finland definitely has a new type of library that they built. And there was a lot of resistance to building it, but this Uti library basically is a rethinking of a traditional space that now brings people together. It is a beautiful building, but what they've done is it's mixed purpose. So not only is it a traditional type of library, you have rooms that you can rent to go and record a podcast. You can rent musical instruments. You can use a 3D printer. They have open like amphitheaters basically, where you have talks that are given and anybody can walk up and see them. The upper level where they have the library proper looks like a bookstore. It's a beautiful space with a cafe in the middle of it. And now what you have is like, I've got a friend there who tells me all the time how his daughter wants to go and hang out there. So you get multi-generations now coming and finding purpose in the space that brings them together. So I think we have to rethink traditional spaces to reignite very personal direct connections.

Jon Bateman: It's so interesting to hear you, when you're talking about the library, mention words other than information. You're mentioning community, cohesion, purpose. Is it that new information systems are driving us crazy? Or is it that the loss of other social processes, other social communities is driving us toward these dark information spaces? Or do we know?

Alicia Wanless: What has happened is that our emphasis on technology has led us to believe that technology can replace those pre-existing forms of community, engagement, connectivity. These are all words that social media platforms had used. So I think that there was this promise that it could somehow replace it when really, again, it's a tool. It is additive. It may help us organize those existing ways in which we were connected, but it cannot replace it. And that's why I think we have to have this kind of return to fostering that if we hope to survive very much at a local level. And we can look at tools to help us do it. But I think, we have, to again, think about all of these things at once while we're constructing that approach.

Jon Bateman: As we wrap up here, I'd like to just go radically meta for a second, because you and I were sitting here, we're talking about an analyzing the information environment, we are also participants, combatants in it, to use your ecological metaphor, we ourselves are information animals trying to survive and thrive in this environment. I'd love to hear your journey here, how you think about your role in this I'll just say for myself I've got this podcast now. A lot of people are watching on YouTube. So my relationship with platforms has become quite different. Now I'm trying to pick thumbnails that would draw people in. I'm trying to get views. And if you're listening to this on YouTube, at some point there will be a little advertisement pop up asking you to like, click and subscribe, right? So you need to make your own choices here as a scholar, as a writer. How do you find your way through this information environment and maintain relevance without losing your identity?

Alicia Wanless: I mean that's a great question because it's something that I've thought about a lot in different parts of my career. I mean I wouldn't even be sitting here today at Carnegie if I hadn't started up a website, a blog. In like 2014 and started putting out ideas of like, how was propaganda changing in a digital age? You know, what would we actually know? So that was quite public. I use social media to a degree, but I never became an influencer. I don't think I ever really could, right? I feel like for my own mental well-being, that would be deeply uncomfortable. But then the question is, how much do you really need to do that to achieve what you're trying to achieve and how much is healthy. So I guess for me, and I've really made a conscious effort in the last couple of years, to balance and prioritize direct engagement interactions with my friends and family in person. And whether that is like, I've got to travel the world for work. Do you want to come and hang out with me while I go and do this thing over there? And inviting friends and families to be a part of that. Or organizing things at a local level like that brings my family together. You know, making sure I go and make those visits. So I think it's an ongoing balance. And it is also remembering that everything that we're experiencing digitally is also somewhat of an illusion and life is very short.

Jon Bateman: Preach, sister, first of all, what you're saying about more time in person with friends and family, I couldn't agree more. And it's hard to think about anything we've been talking about that would get worse by doing that. I think that can only help things get better. Alicia, this has been a great conversation. Thanks for coming on the show.

Alicia Wanless: Thanks for having me, Jon.

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from The World Unpacked

- Every War Is Now a Drone WarPodcast Episode

Steve Feldstein, a leading expert on technology and warfare, joined Jon Bateman on The World Unpacked to break down these trends. Are drones helping defenders deter aggression, or enabling attackers to slaughter more civilians? Why haven’t we seen full autonomy? And has the U.S. fallen behind in the weapon class that it first pioneered?

Jon Bateman, Steve Feldstein

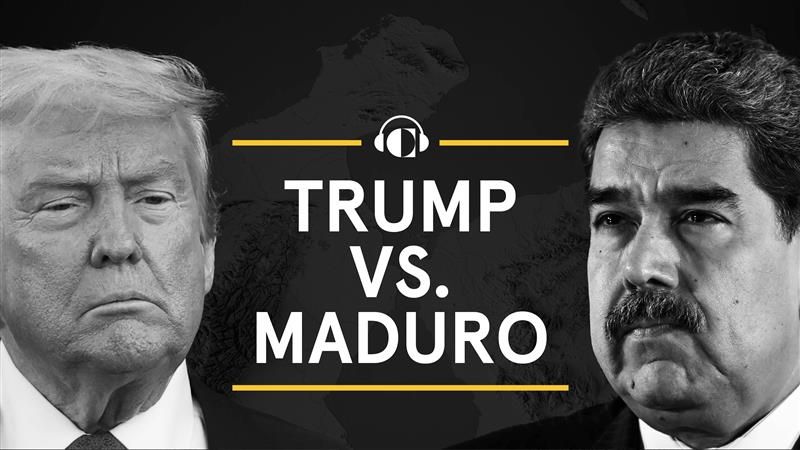

- Testing the Case for Regime Change in VenezuelaPodcast Episode

Ambassador James B. Story most recently served as U.S. Ambassador for the Venezuela Affairs Unit, located at the United States Embassy in Bogotá, Colombia. Previously, Ambassador Story served as Chargé d’Affaires at the Venezuela Affairs Unit and, prior to mid-2019, the United States Embassy in Caracas, Venezuela.

Jon Bateman, James B. Story

- Decoding Trump’s Foreign Policy BlueprintPodcast Episode

Stephen Wertheim is a historian, strategist, and author of Tomorrow, the World: The Birth of U.S. Global Supremacy. He joins Jon Bateman, host of The World Unpacked, to assess what this historic document can tell us. Will Trump follow it? Which GOP factions were behind it? And how will it shape the battle of ideas in 2028 and beyond?

Jon Bateman, Stephen Wertheim

- AI’s Biggest Skeptic Sees a BubblePodcast Episode

Author, podcaster, publicist, and one of AI's biggest critics joins The World Unpacked to discuss the AI bubble and his own research into AI finances with Jon Bateman.

Jon Bateman, Ed Zitron