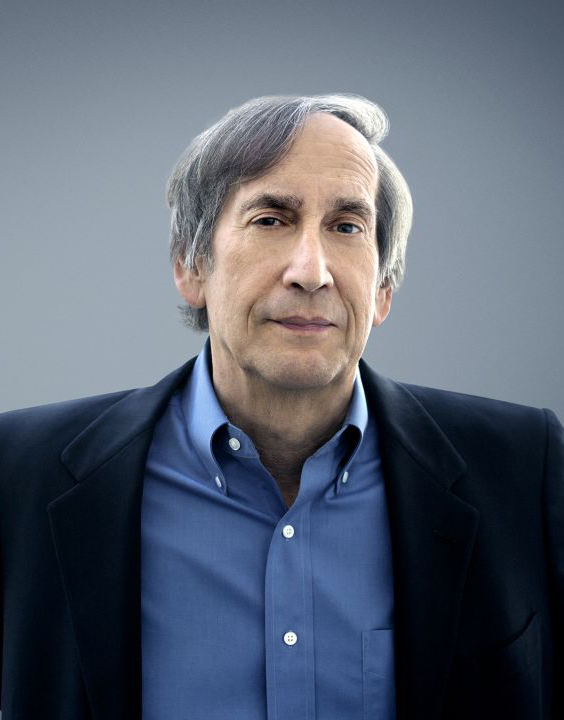

Dmitri Trenin

{

"authors": [

"Dmitri Trenin"

],

"type": "legacyinthemedia",

"centerAffiliationAll": "",

"centers": [

"Carnegie Endowment for International Peace",

"Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center"

],

"collections": [],

"englishNewsletterAll": "",

"nonEnglishNewsletterAll": "",

"primaryCenter": "Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center",

"programAffiliation": "",

"programs": [],

"projects": [],

"regions": [

"North America",

"United States",

"Caucasus",

"Russia",

"Eastern Europe"

],

"topics": [

"Foreign Policy"

]

}

Source: Getty

Kosovo: A Case for a European Dayton

European, American and Russian diplomats continue to work against the December deadline for Kosovo’s pre-announced unilateral declaration of independence (UDI). However, few hope for an agreement. Belgrade and Pristina have not budged. Washington and its major allies are adamant that Kosovo can not be held indefinitely in the protectorate limbo and must be given independence.

Source: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung

Meanwhile, the formula for solving the conflict has been more or less clear for some time. To begin with, one has to accept that the Kosovars will not be ruled by the Serbs, and vice versa. Maintaining the status quo is a losing proposition. Creating a multiethnic, but in reality an Albanian-dominated Kosovo is trading one problem for another. The Kosovars must be given full independence, and the Serbs must be allowed to join Serbia. After everything that the Kosovars and the Serbs have gone through, partition is the least bad option. The Serb-populated area north of the Ibar River would probably vote in a referendum to unite with Serbia, and the rest of the province would form a Kosovar state. Universally recognized and invited to join the UN, independent Kosovo will be made responsible for respecting the rights of those Serbs who would stay within its borders after the partition, and for the Serbian Orthodox cultural sites. Those Serbs who decide to leave their homes in the Kosovar state must be given resettlement assistance.

How to achieve this? At the moment, the United States is too focused on the Middle East to pay any serious attention to the Balkans. In fact, it wants to close the issue soonest to free up resources for use elsewhere. Russia is largely irrelevant in the region, except when it comes making excuses in Belgrade and taking a vote at the UN Security Council. True, Moscow’s position in defense of territorial sovereignty is a principled one, not a mere bargaining chip, but it calls for Belgrade’s consent, not the immobility of the borders. It is Europe, however, that is both the principal outside player and the one most intimately involved on the ground. It should step to the fore. Taking a leaf from the Americans’ book, the EU needs to do another Dayton, under its own leadership.

Both antagonists, Serbia and Kosovo, are future EU territory, and need be treated as such. Serbia itself, for its acceptance of the loss of much of Kosovo, should be given a time plan for EU accession, as well as generous financial assistance to help the transition and get over the trauma of the territorial loss. Kosovo, too, must be given a clear European perspective and continued assistance, conditional on its ability to modernize the economy, build institutions and eradicate crime. To make the parties clinch a deal won’t be easy, but once the deal is on, governments who have made it might have to resign, but the accord is likely to remain intact.

In 1995, then U.S. President Clinton virtually kept the leaders of Serbia, Croatia and Bosnia under lock and key at a USAF base in Dayton, Ohio, until they reached an agreement on the conflict in Bosnia-Herzegovina. Whatever can be said about Bosnia 12 years later, there is peace on the ground and it is off the world’s agenda. Bill Clinton’s experience should inspire others. The Europeans and the French in particular could borrow a page from the Dayton story. They need to tell the Americans and the Russians that they can manage on their own. Washington should feel relieved. Moscow must be satisfied that its stated principle: no border change without the sovereign state’s consent, shall be met. After that, the choice will be between the splendor of Rambouillet, if the parties see the light sooner, or at some more austere French air force base in the Massif Central, if one has to go for some heavier lifting. With so many cards in Europe’s pack, it is difficult to see how the EU can fail. Its diplomatic success will not only resolve one of the last major problems in the Balkans. As a result, there will be more of Europe around, and more of a union within it.

A decision to go for conflict resolution is inherently risky. National and personal credibility will be put to a serious test. However, the costs of inaction, too, will be considerable at best, and disastrous at worst. They, too, need to be taken into account. The French President, acting in close cooperation with the German Chancellor and the fellow EU leaders, would do right if he tried to turn the challenge into a chance. In facing the former and reaching to the latter, he would deserve the support of the United States, especially in Pristina, and of Russia, particularly in Belgrade.

Dmitri Trenin is a Senior Associate of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and Deputy Director of its Moscow Center.

This article originally appeared in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

About the Author

Former Director, Carnegie Moscow Center

Trenin was director of the Carnegie Moscow Center from 2008 to early 2022.

- Mapping Russia’s New Approach to the Post-Soviet SpaceCommentary

- What a Week of Talks Between Russia and the West RevealedCommentary

Dmitri Trenin

Recent Work

Carnegie does not take institutional positions on public policy issues; the views represented herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of Carnegie, its staff, or its trustees.

More Work from Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

- Indian Americans Still Lean Left. Just Not as Reliably.Commentary

New data from the 2026 Indian American Attitudes Survey show that Democratic support has not fully rebounded from 2020.

- +1

Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Andy Robaina, …

- Taking the Pulse: Can European Defense Survive the Death of FCAS?Commentary

France and Germany’s failure to agree on the Future Combat Air System (FCAS) raises questions about European defense. Amid industrial rivalries and competing strategic cultures, what does the future of European military industrial projects look like?

Rym Momtaz, ed.

- Can the Disparate Threads of Ukraine Peace Talks Be Woven Together?Commentary

Putin is stalling, waiting for a breakthrough on the front lines or a grand bargain in which Trump will give him something more than Ukraine in exchange for concessions on Ukraine. And if that doesn’t happen, the conflict could be expanded beyond Ukraine.

Alexander Baunov

- Russia in Africa: Examining Moscow’s Influence and Its LimitsResearch

As Moscow looks for opportunities to build inroads on the continent, governments in West and Southern Africa are identifying new ways to promote their goals—and facing new risks.

- +1

Nate Reynolds, ed., Frances Z. Brown, ed., Frederic Wehrey, ed., …

- Trump’s State of the Union Was as Light on Foreign Policy as He Is on StrategyCommentary

The speech addressed Iran but said little about Ukraine, China, Gaza, or other global sources of tension.

Aaron David Miller